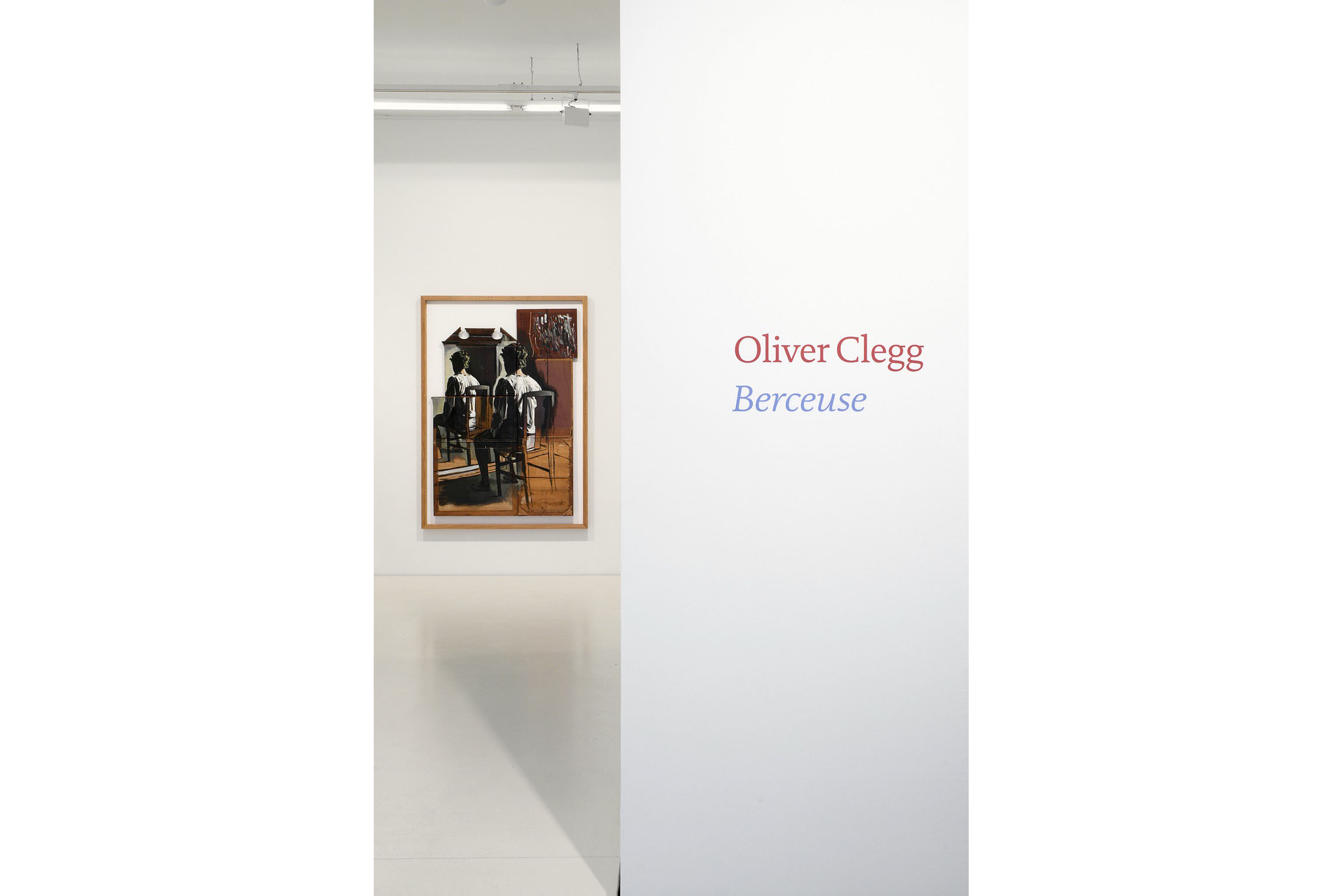

Oliver Clegg

Berceuse

Works

Zugzwang

2010

Oil on 14 chess boards and artist’s frame

230.2 × 161.5 cm

Plato is Bore

2010

Oil on dismantled Edwardian school desk and artist’s frame

140.2 × 118.5 cm

I

2010

Oil on floorboards from demolished church and artist’s frame

293.3 × 143 cm

Think of Me

2010

Oil on the back of 6 mirrors and artist’s frame

215.7 × 153.7 cm

Think of Me (Detail)

2010

Oil on the back of 6 mirrors and artist’s frame

215.7 × 153.7 cm

Piano Forte

2010

Oil on dismantled piano and artist’s frame

253.5 × 165.6 cm

In Words Drown I

2010

Oil on dismantled blanket chest and artist’s frame

204.7 × 283 cm

In Words Drown I (Detail)

2010

Oil on dismantled blanket chest and artist’s frame

204.7 × 283 cm

II

2010

Oil on floorboards from demolished church and artist’s frame

239.8 × 159.5 cm

Begin

2010

Wooden cradle

48.5 × 81 × 27.5 cm

Begin

2010

Wooden cradle

48.5 × 81 × 27.5 cm

About

British artist Oliver Clegg (b 1980) has gained a reputation as a multi-faceted artist whose meticulously executed works hover between two and three-dimensional disciplines. A masterful draughtsman and skilled painter, Clegg is paradoxically one of the most conceptually minded young artists working today, engaging with language, narrative and memory and drawing from symbolism and surrealism in his practice.

Playing as he likes to with words in different languages, Clegg found himself returning time and again to: ‘berceuse’, the French for lullaby. The word became the genesis for a new body of work and the title for the artist’s first solo show in Berlin. Clegg was struck by the onomatopoeic quality of ‘berceuse’; the way it mimics the soothing sound of a parent coaxing their child into dreamland. Dreams are significant to the artist as a means for creating a space that seems half way between the real and the surreal. And indeed the surrealist notion of ‘the harmony of disharmonious elements’ is keenly important to him and evident in this exhibition. By including objects that have strong symbolic meanings but that appear to be behaving in ways only comprehensible in this dream world, the artist can introduce a playful element into his work.

Play is a motif that has run throughout Clegg’s practice to date, as exemplified by his paintings of discarded toys, executed on found drawing boards. The objects speak of private nostalgias but evoke commonly held experiences of the moment when the child ‘gives up’ a treasured blanket or toy. Though it is the object that disappears, often far more is lost. In his essay, ‘Creative Writers and the Daydream’, Freud states that though the fantasy world of childhood is lost to grown ups, it can be kept alive by writers and artists in their work. This is of key importance to Clegg.

Clegg is sensitive to the significance of ordinary objects, transformed in the hands of a writer or an artist. This act of recycling began when Clegg was still at art school. He collected old drawing boards, prizing them for their scratchings and doodles. Clegg likes the fact these come with their own unique histories that relate to somebody else‘s life. Emotive objects such as a diary or well-thumbed book, a school desk, blanket box, chess-set or even floorboards from a de-consecrated church, acquire a noble quality in Clegg’s hands. By working with these artefacts, Clegg allows the viewer to wander between narratives and worlds, uniting extant references with new images, or creating entirely new ones, recalling Duchamp: ‘it is the onlookers who make the pictures’.

Continue reading

For this exhibition Clegg has produced seven new paintings and a sculpture. The show commences with ’Begin’ a wooden cradle with its title carved into its bottom. The cradle is symbolic of the start of life’s journey and, thus its association with death as well as with life, is unavoidable. An empty cradle is also suggestive of the child having grown up. Once it was lulled by its mother to sleep, but now as it moves through childhood, it must settle itself, the night no longer offering a welcome escape from the day, instead bringing an onslaught of dreams.

‘Think of Me’ depicts a double self-portrait of the seated artist viewed from behind. He appears to be looking in a mirror, yet sees not his reflection but the view the observer is confronted with: the back of his head, thus calling into question the artist’s sense of identity. The work is clearly a homage to Magritte but by Clegg painting the image on an assemblage of found mirrors it is as if he is being judged against the others who have looked in these mirrors before him; the work is pregnant with the artist’s sense of emotional conflict, and with the dreams and everyday concerns of all those who have peered into the mirrors.

The German word ‘Zugzwang’ is an international chess term meaning ’you have to make a move’. With his use of chiaroscuro and the posing of the figure in a manner typical of the Italian Baroque, Clegg’s self portrait is both intriguing and sensuous. Painted on the back of fourteen found chess boards, an already loaded surface, the work derives from the premise of conflict: in this case between tragedy and comedy, as attested by the presence of the two masks. Each board has seen many games so it is possible to think about this work as the sum of the energy of multiple minds while simultaneously reflecting the warring emotions of the artist.

The title ‘In Words Drown I’ is a palindrome, it spells the same backwards as well as forwards. The painting features a girl reaching out to her sleeping self. The depicted scene recalls an example of reflexive vision given by the phenomenologist, Maurice Merleau-Ponty. He challenged Descartes’ claim that because the world is external to the artist, in order to know it, the artist attempts to recreate it. This argument of Descartes gave art history a representationalist understanding of vision and art. Merleau-Ponty challenged this view by claiming that because the artist moves through the world at the same time as looking at it, the world cannot be external to him: he sees both the world – and himself in that world. Merleau-Ponty illustrates his argument through the use of the following paradoxical analogy: if I touch myself, I am both touching and being touched; but both actions are experienced by me. In the case of Clegg’s painting, the subject is reaching out to her sleeping self, the conscious mind sinking, or ‘drowning’ in the sub-conscious.

Clegg enjoys word games and ‘Piano Forte’, painted on a dismantled piano, is one such example. Though the title describes the physical essence of the piano, the words also mean ‘soft’ and ‘strong’; perhaps another reference to the dichotomy of the self who finds himself divided between what he thinks and feels and what he can actually express.

The paintings ‘I’ and ‘II’, feature isolated, domestic objects: a floating pillow and a floating chair, painted on floorboards recovered from a demolished church. The fact the chair in ‘II’ is floating suggests it has transcended its normal function and gained a sentimental, even spiritual dimension. Maybe this chair was once associated with a particular owner and is thus imbued with sentimental significance. That objects can be powerfully emotive signifiers is no surprise but the added component of the objects floating is perturbing, suggestive even of the ascension of the spirit. Again Clegg presents the viewer with a conundrum: the chair is an object associated with grounding the human in earthly space. The pillow in ‘I’ on the other hand has an aerial quality. Clegg has identified two of the most essential objects associated with helping the human through day and night. That the chair is another symbol of the conscious mind, and the pillow of the subconscious, is perhaps deliberately unclear, the viewer being again reminded of Duchamp’s phrase concerning his role in the process of looking at art.

‘Plato is a Bore’ concludes the exhibition. The work consists of a dangling puppet painted on a dismantled Edwardian school desk. The puppet reminds Clegg of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave which describes a group of people who have been chained to the walls of a cave all their lives. Shadows are cast on the walls by people outside the cave walking by, and over time the cave’s inhabitants ascribe forms to these shadows. It is not until one of the people is freed from the cave that he realises the shadows do not constitute reality at all, merely a puppet theatre version of it. Plato’s analogy was intended to explain the importance of knowledge governing sensation. Clegg’s hanging puppet serves to remind the viewer that experience needs to be accompanied by knowledge. The title of this piece could well have been scrawled on the desk itself by a bored schoolboy who has not yet emerged from ‘the cave’.

Oliver Clegg lives and works in Cornwall and London.

— Jane Neal