Christoph Hänsli

Stollen X

Works

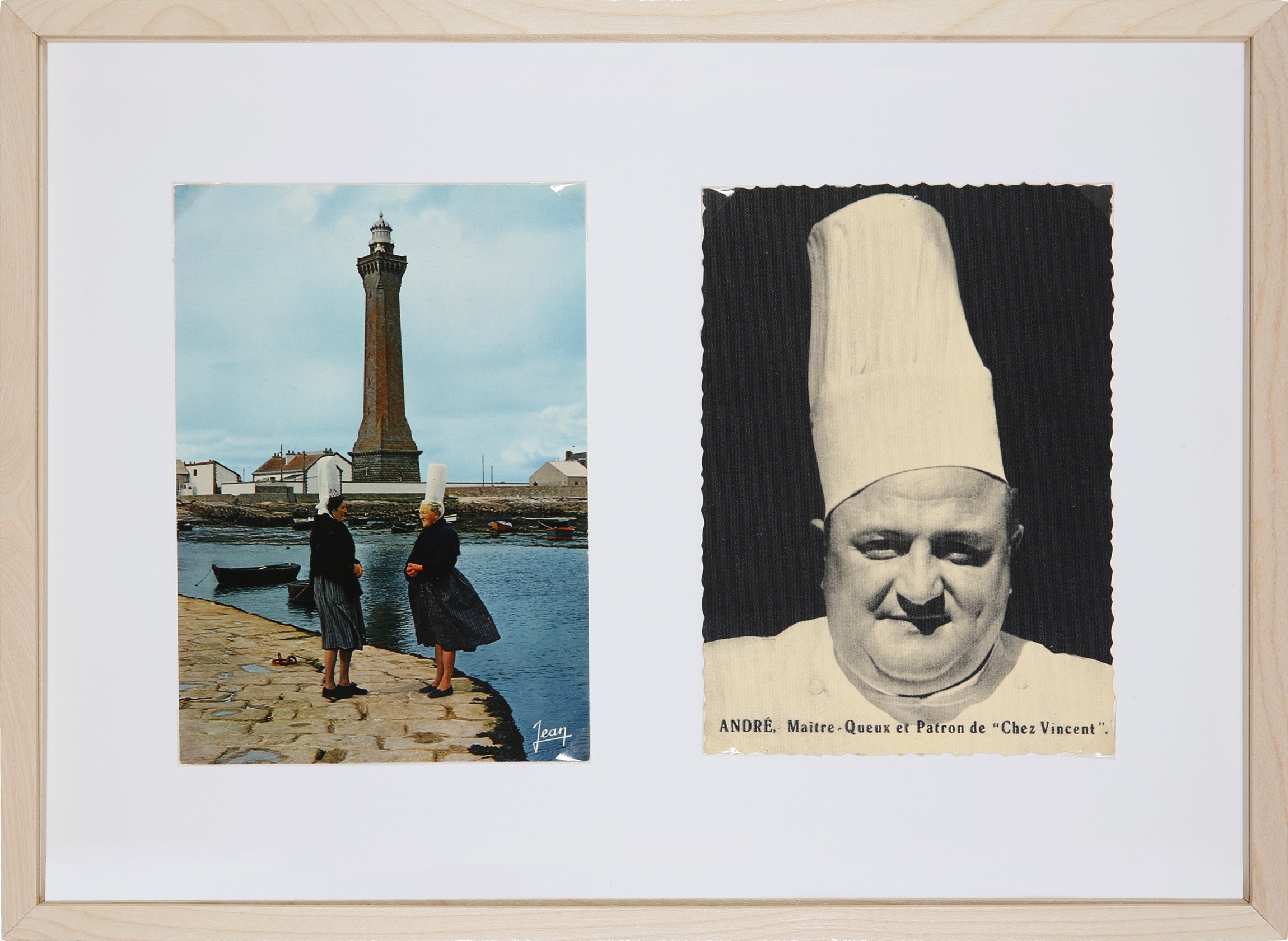

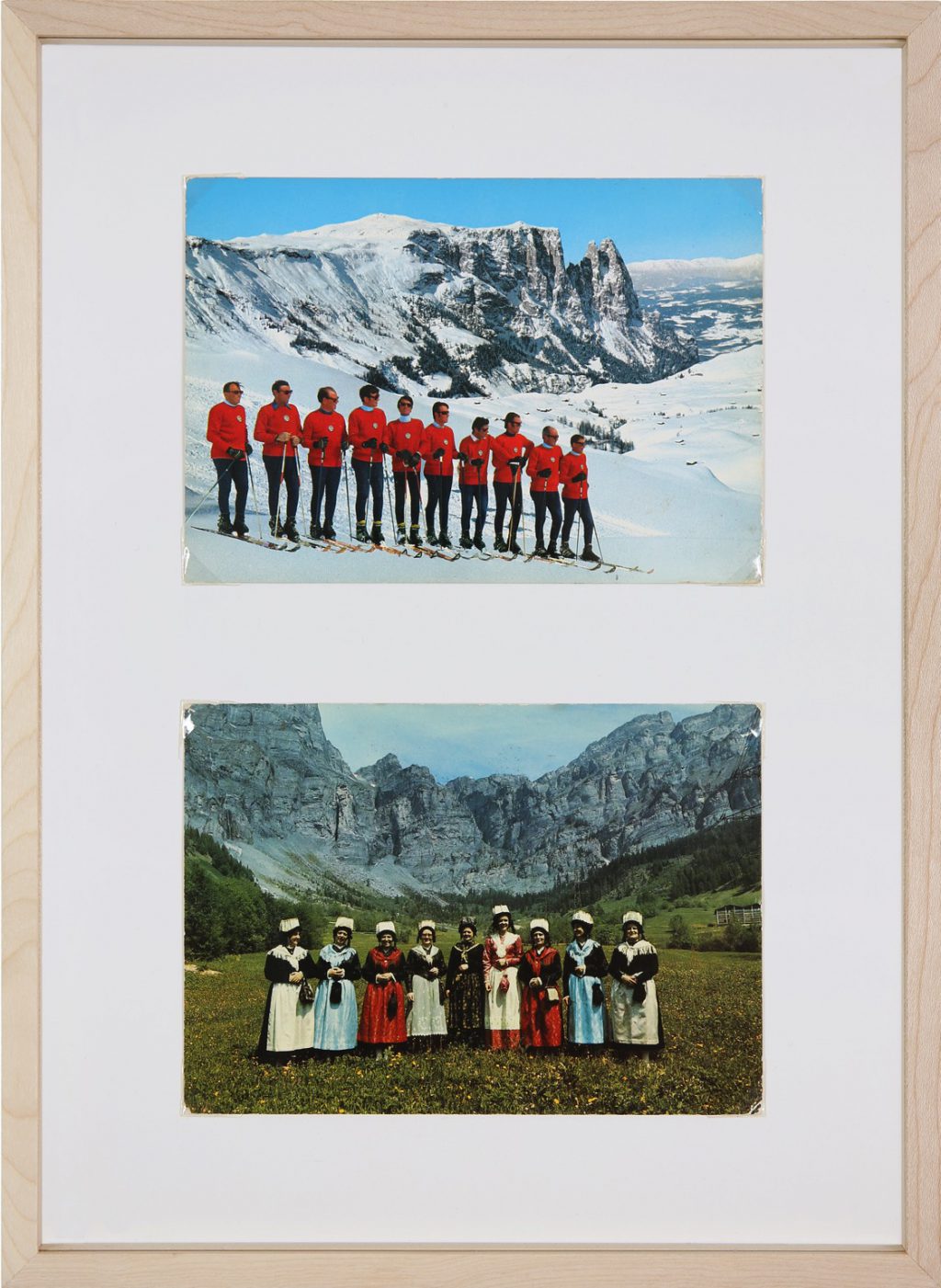

Form follows function

2012

Postcards, artist’s frame

23.7 × 32.4 cm

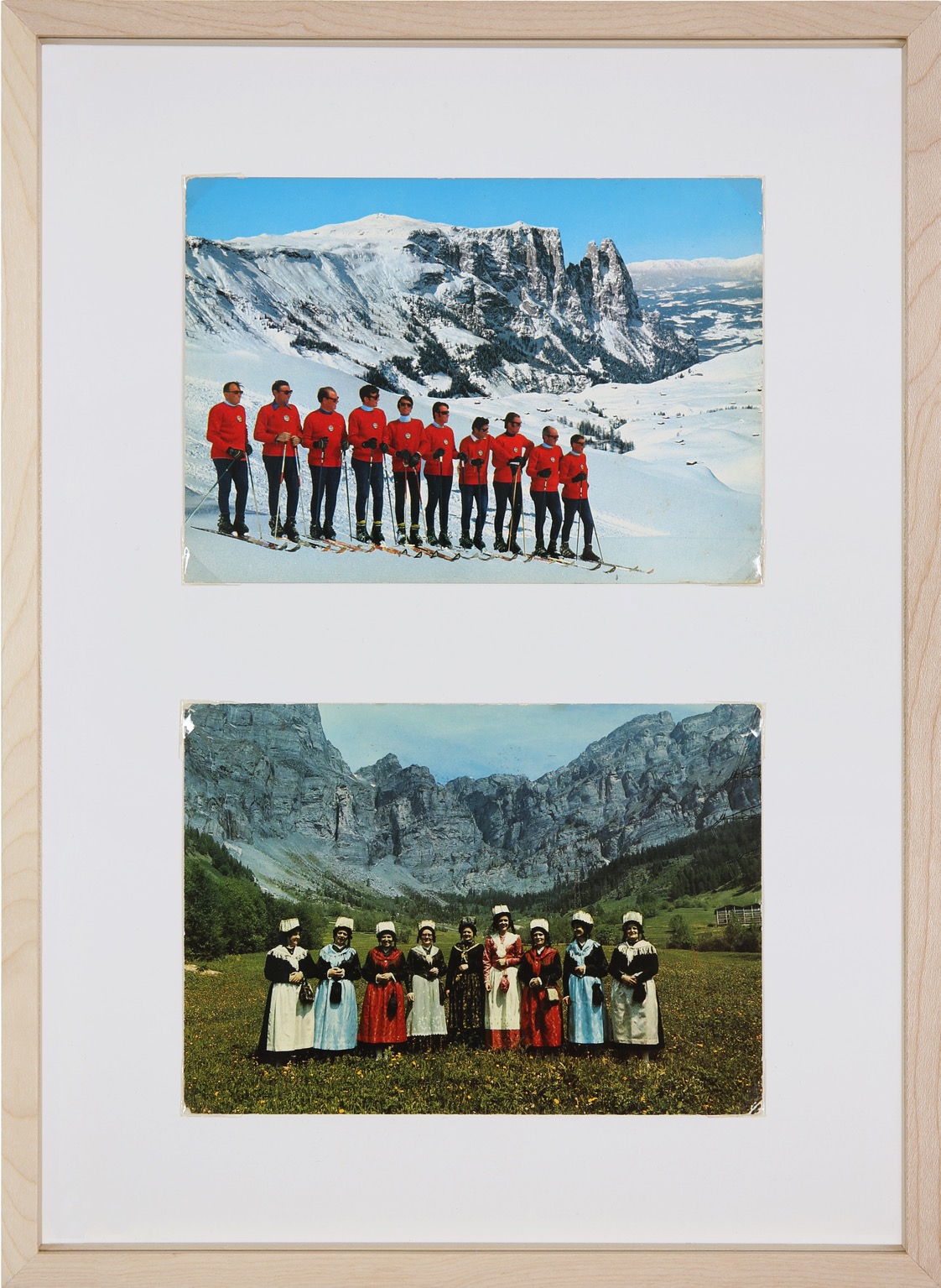

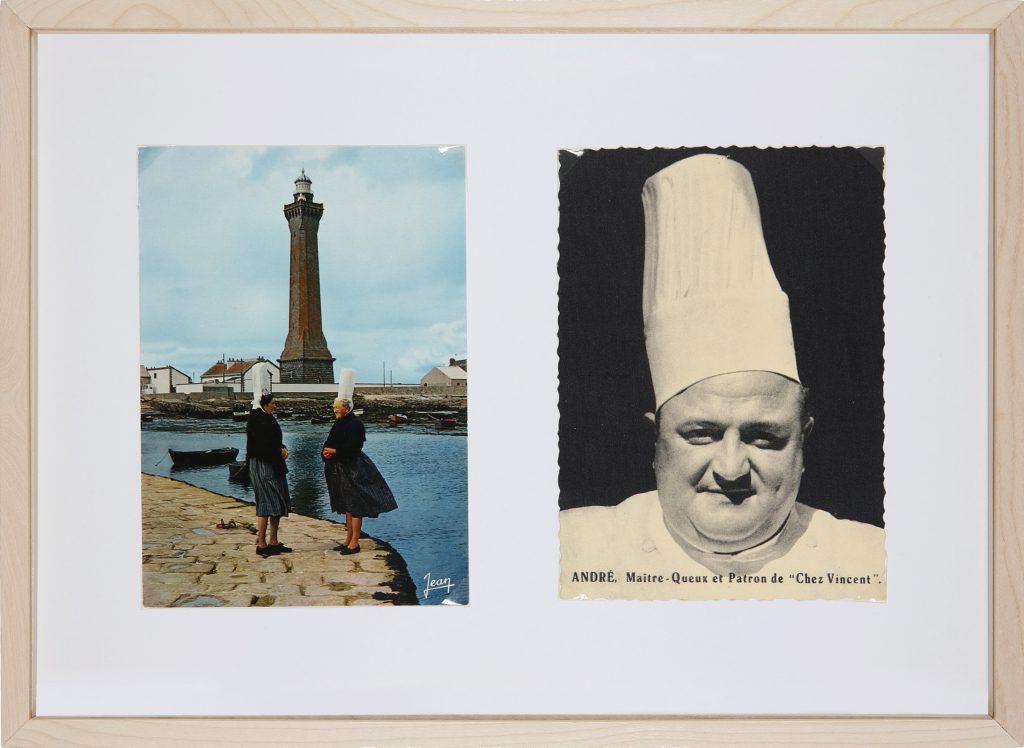

Anthropologische Konstante B

2012

Postcards, artist’s frame

32.4 × 23.7 cm

“Liebe Eltern, Herrliches Wetter! Wir unternehmen sehr lange Wanderungen. Kommt bitte am Samstag um 15.14 Uhr an den Bahnhof. Ich kann den schweren Koffer nicht tragen. Herzliche Grüsse, Graziella”

2014

Kitchen towels and wallpaper, artist’s frame

74.5 × 96 × 14 cm

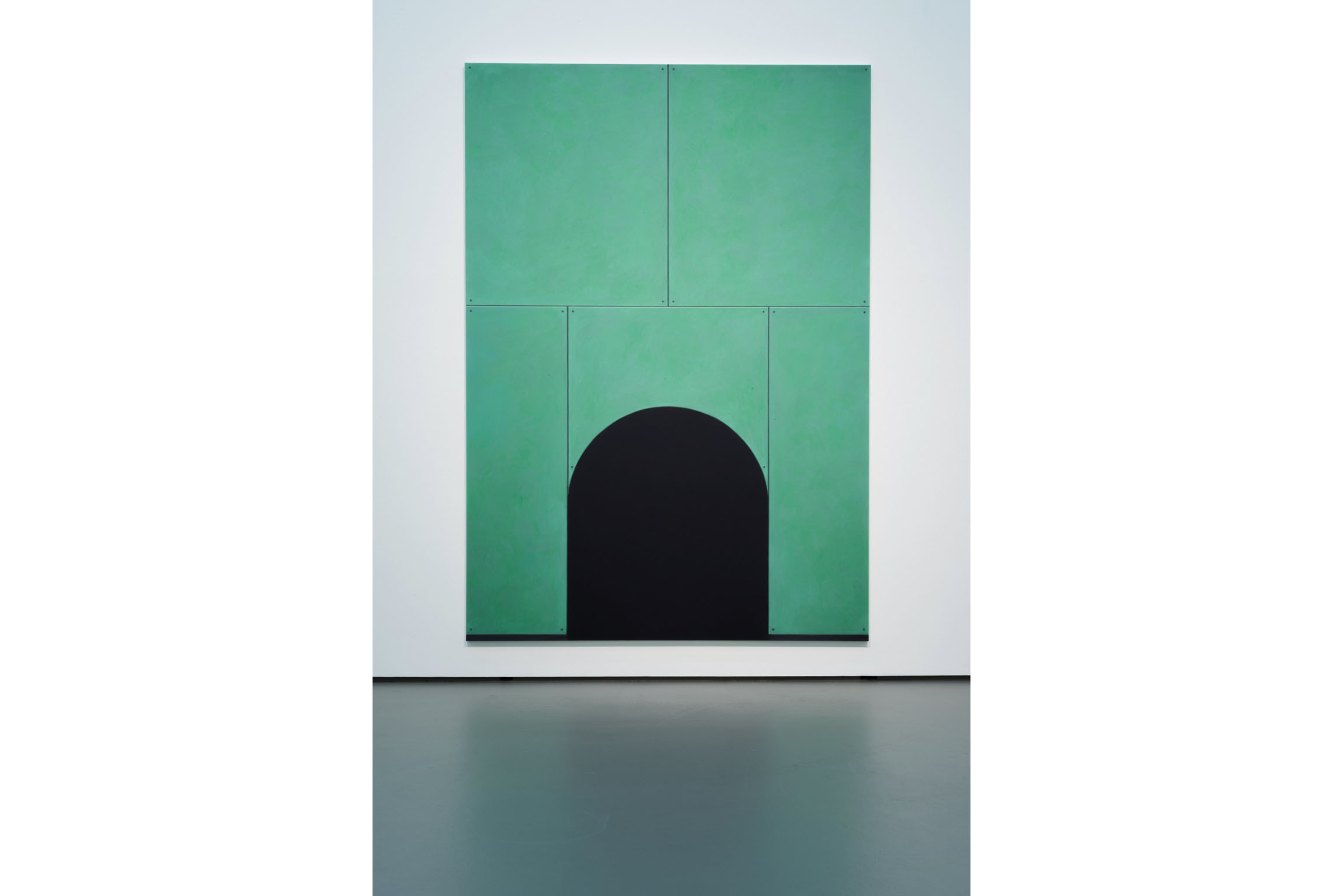

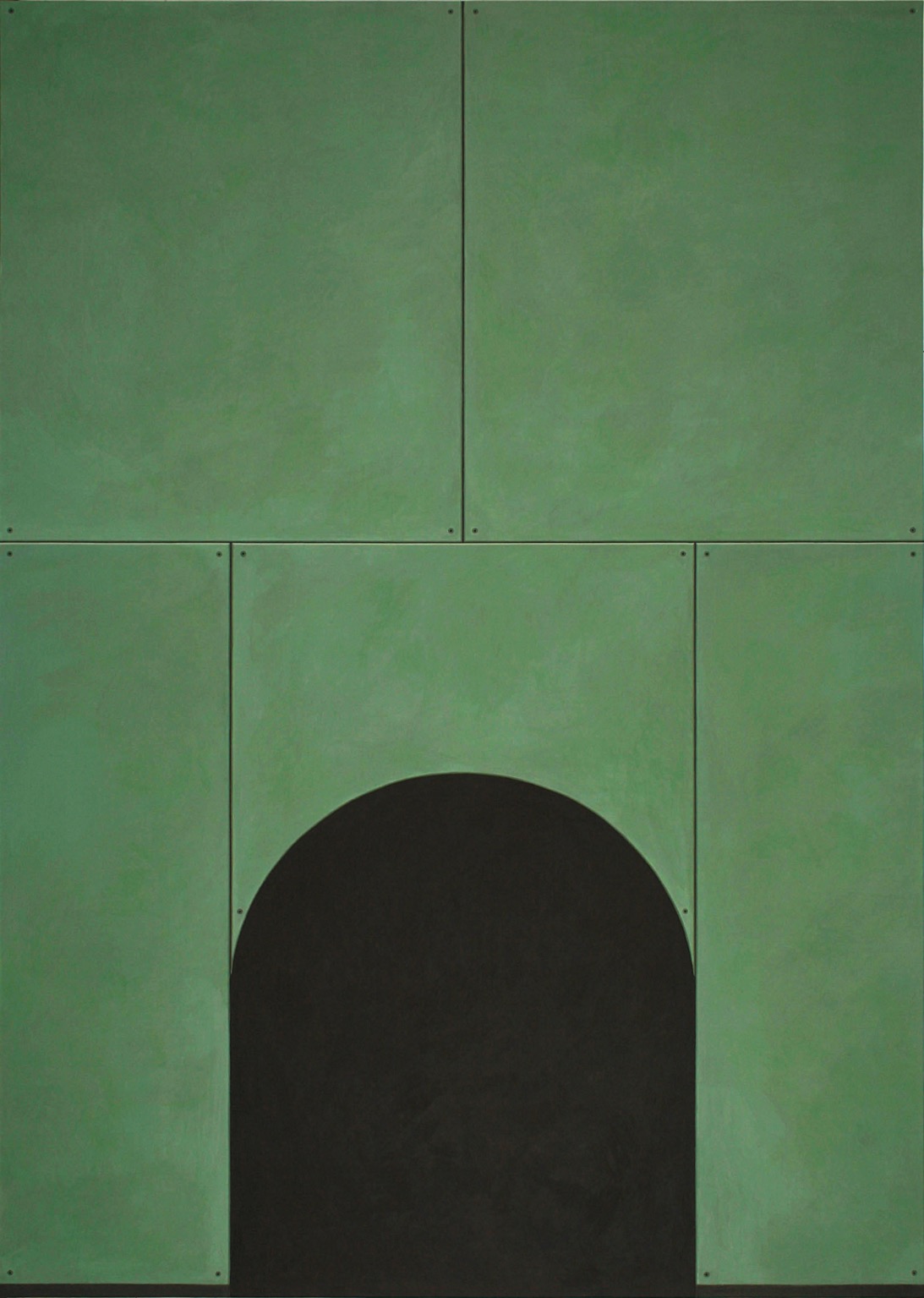

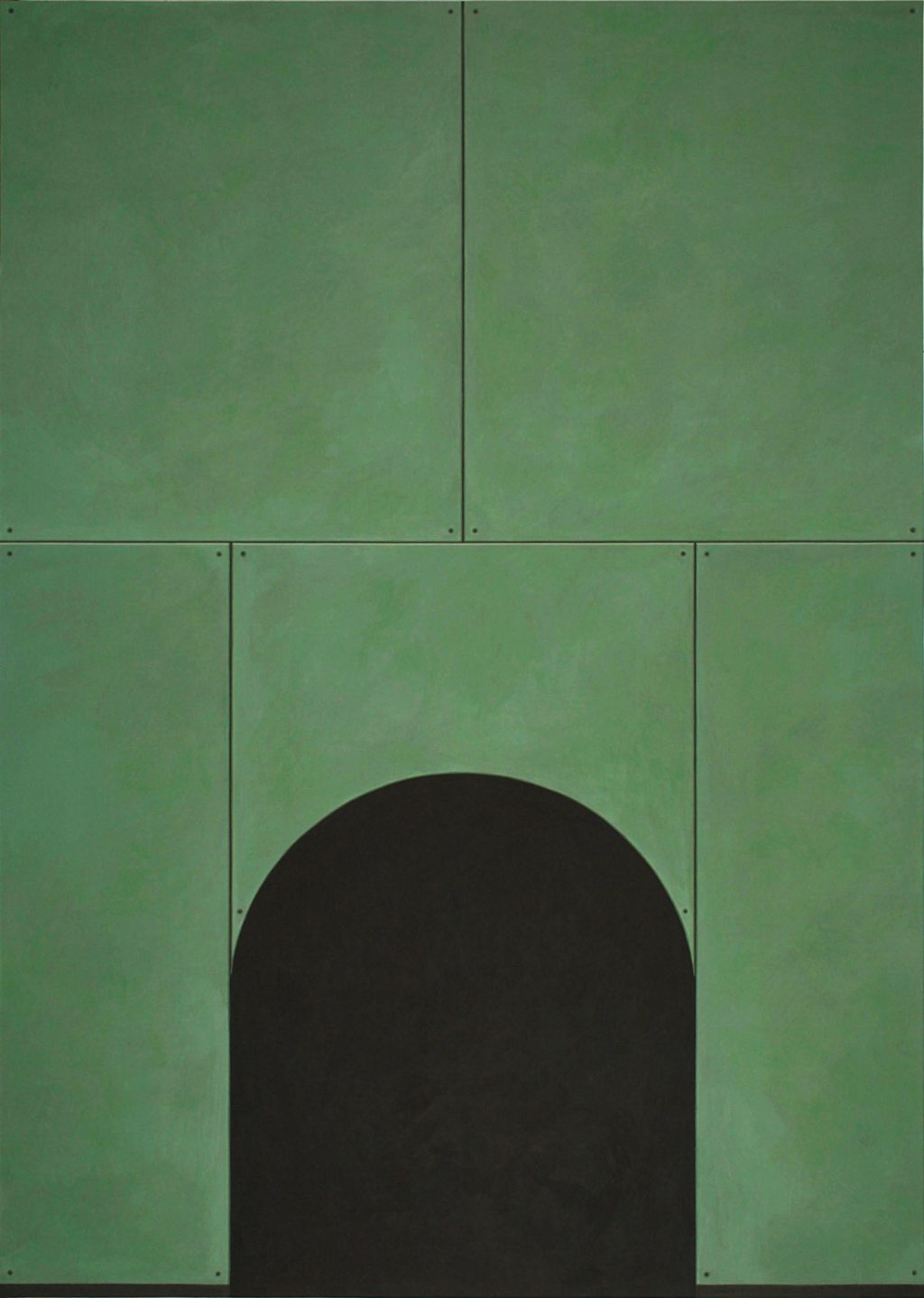

Ofen Krematorium Nordheim

2012

Acrylic on cotton

285 × 200 cm

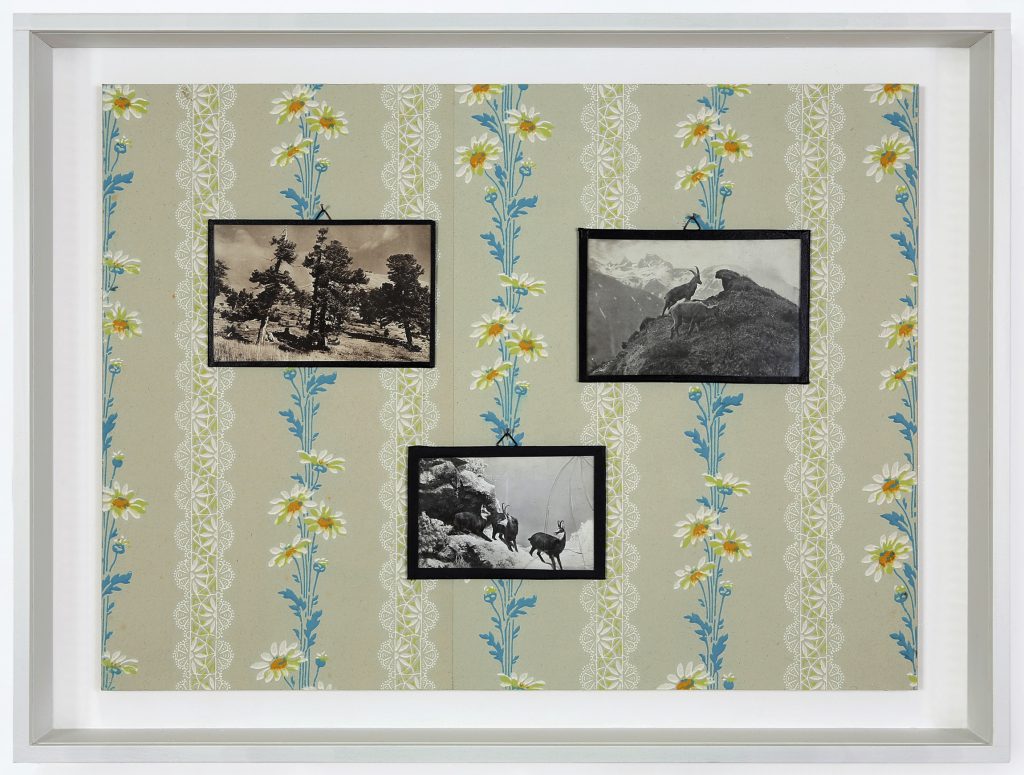

Nationalpark

2014

Photographs on wallpaper, artist’s frame

54.5 × 72.5 × 8 cm

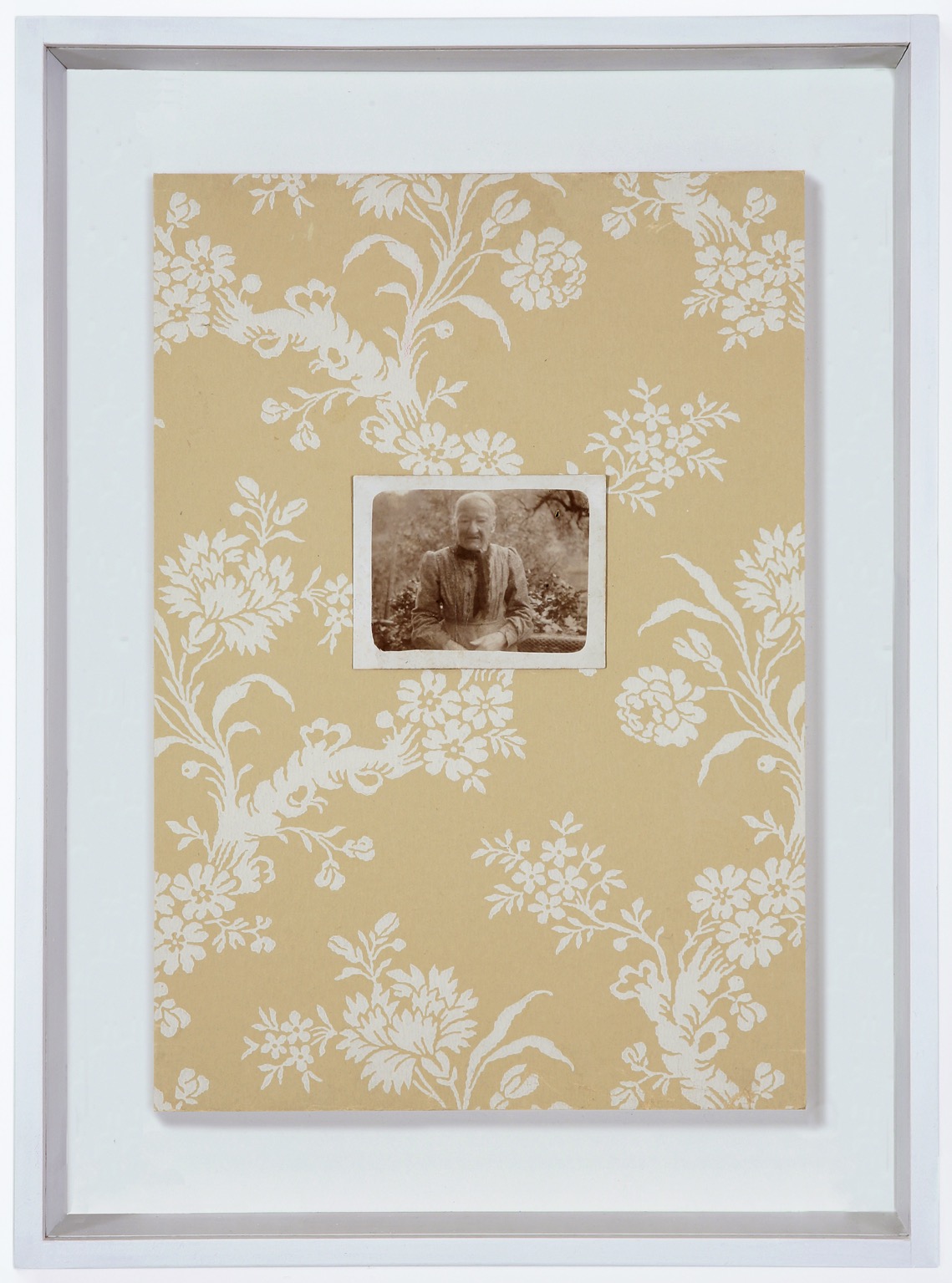

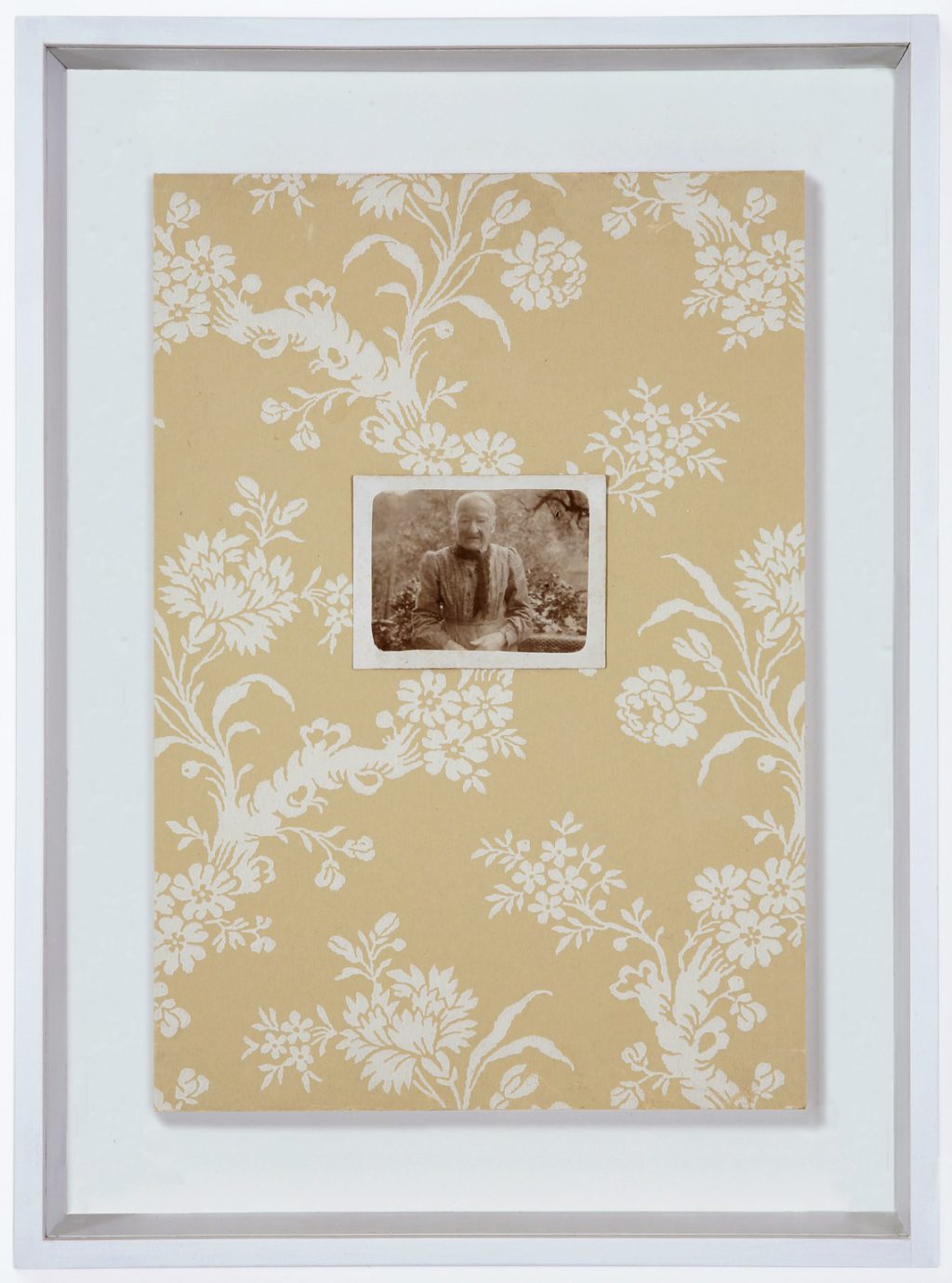

La visite

2014

Photographs on wallpaper, artist’s frame

55.5 × 41 × 8 cm

Untitled

2014

Photographs, artist’s frame

18.5 × 31.5 × 5.5 cm

Besuchszeit

2014

Found objects, artist’s frame

26.5 × 83.5 × 22.5 cm

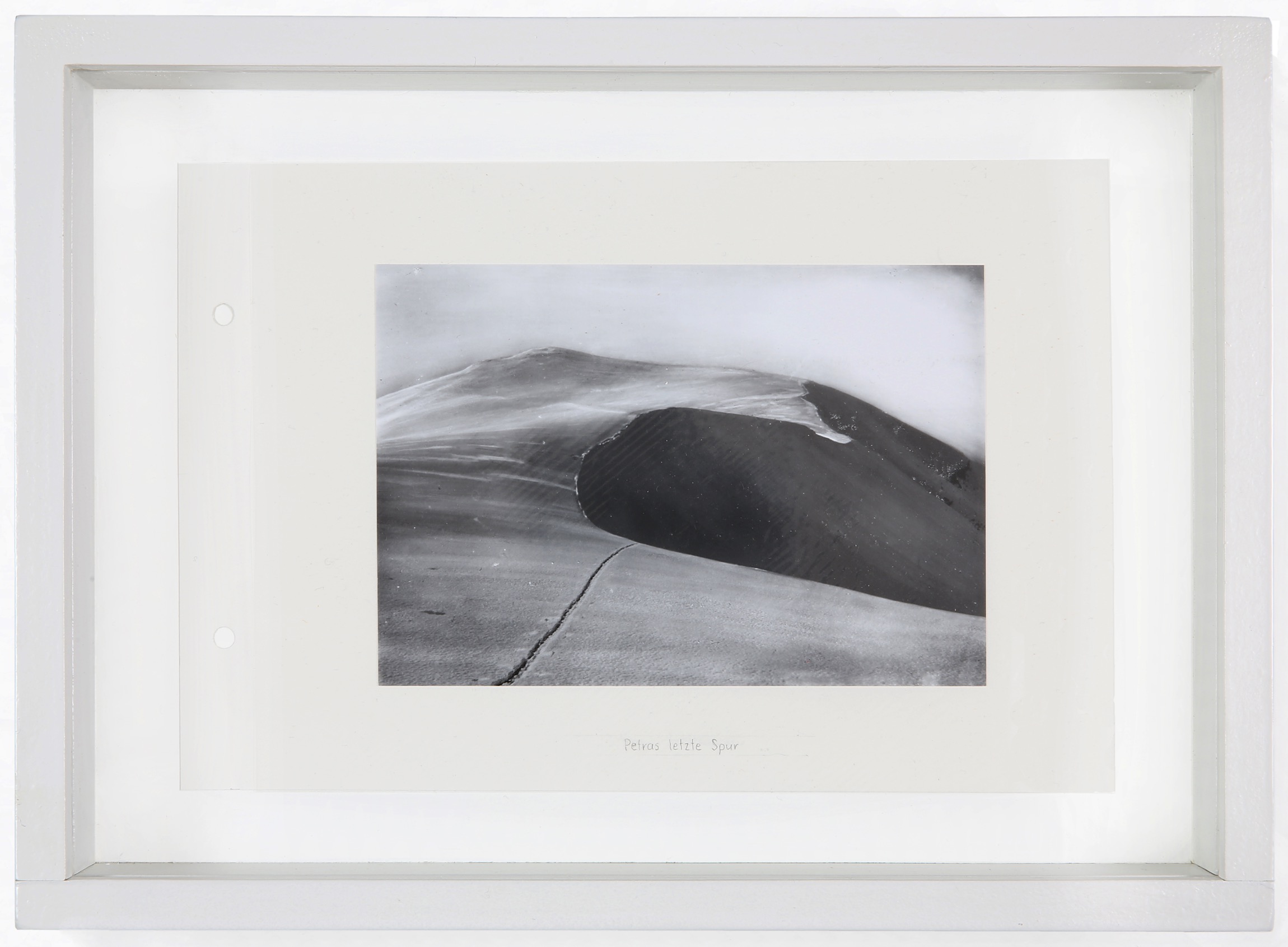

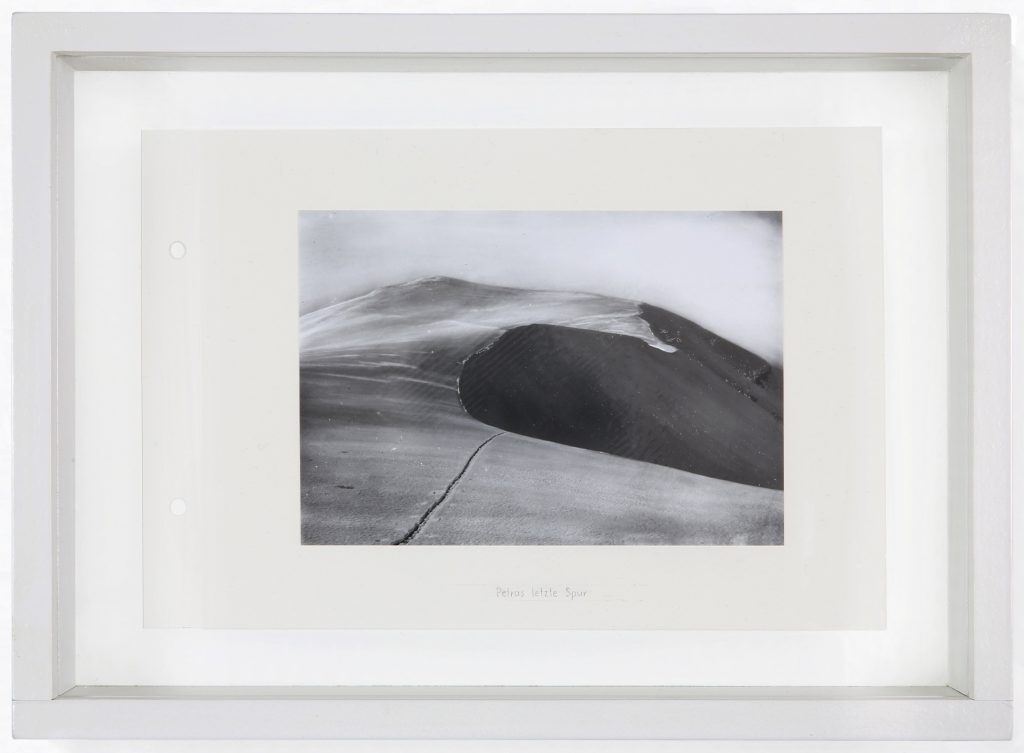

Petras letzte Spur

2014

Photograph, artist’s frame

21.5 × 29.5 × 5.5 cm

Wahlschalter

2014

Acrylic on cotton on MDF

46 × 40 cm

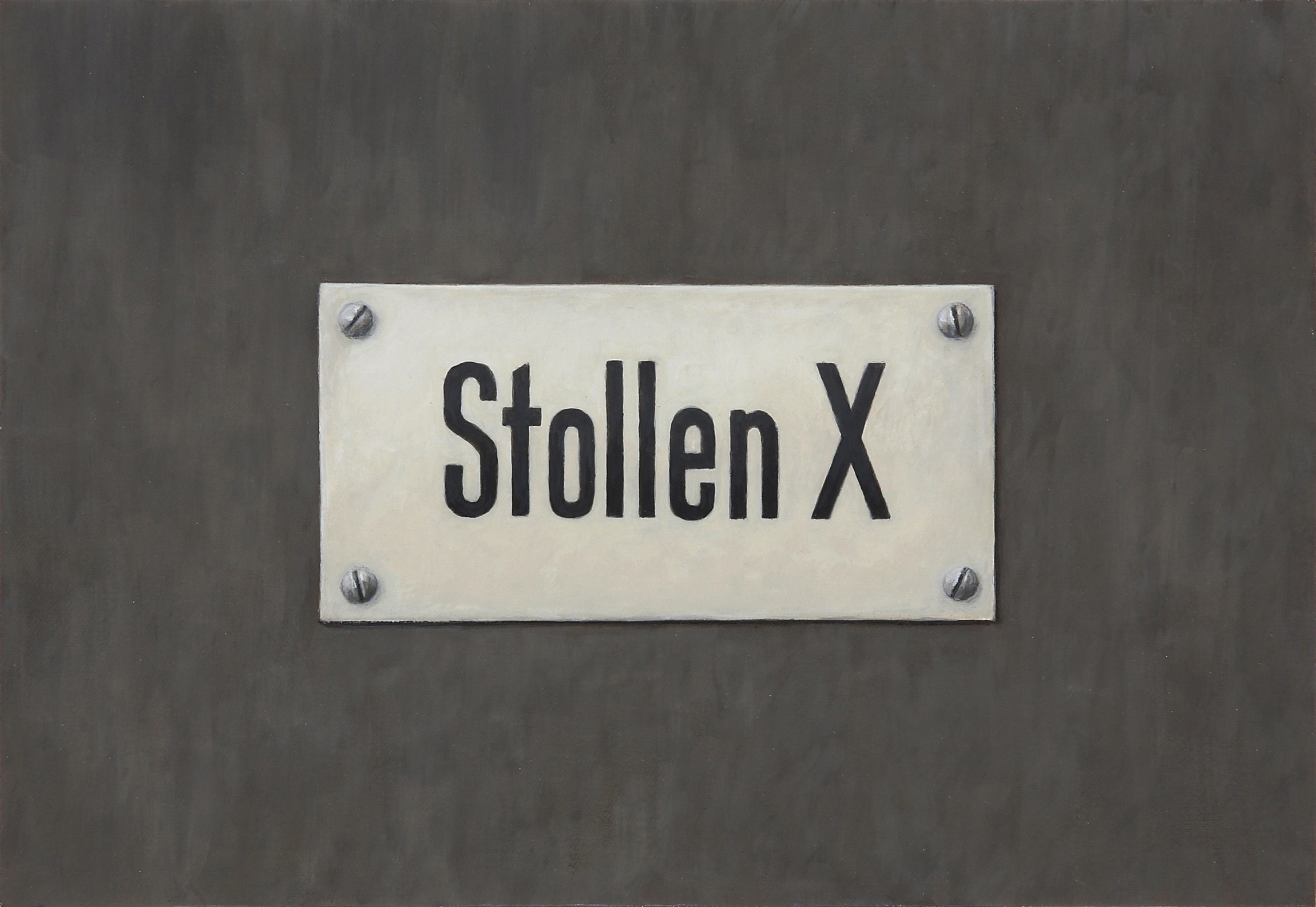

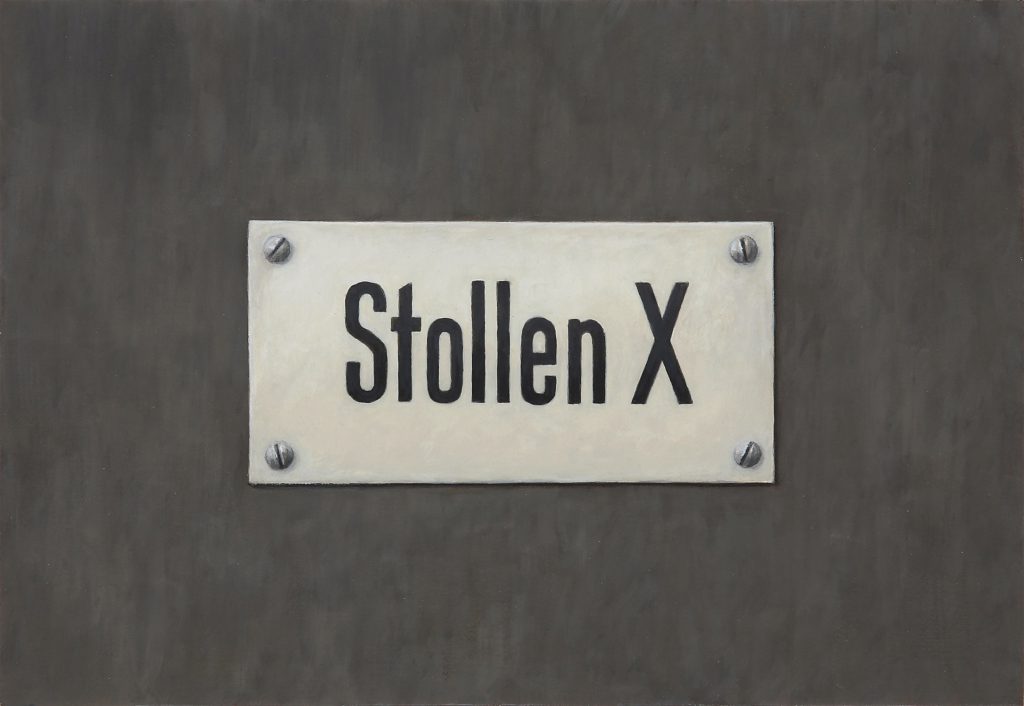

Stollen X

2014

Acrylic on cotton on MDF

20 × 29 cm

All Off

2014

Acrylic on cotton on MDF

24 × 19 cm

Lüftungsabdeckung

2012

Acrylic on cottom

56 × 90 cm

Kleidersammlung

2012

Acrylic on cotton

147 × 99 cm

Kartonboxen

2012

Acrylic on cotton

112 × 73 cm

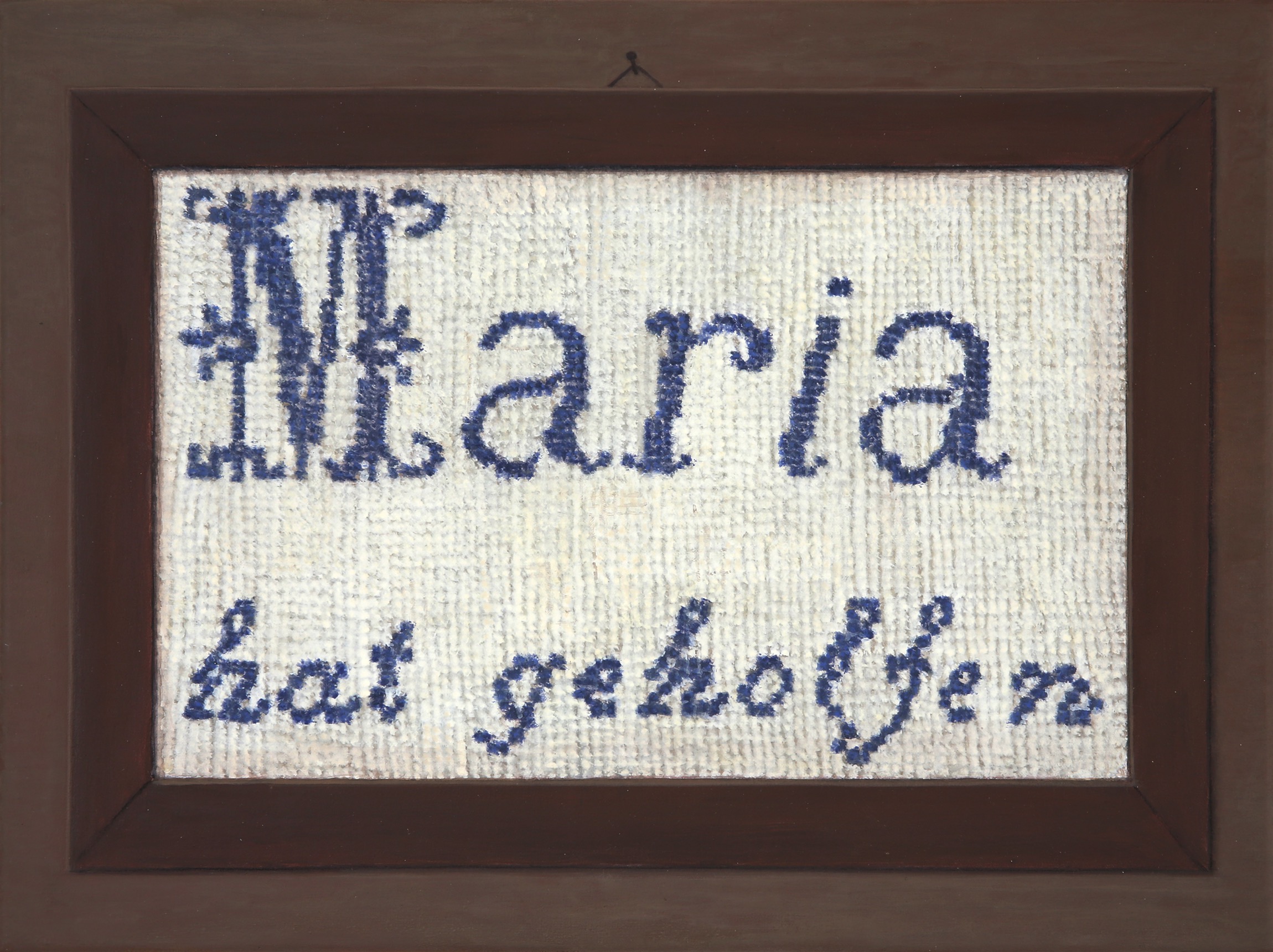

Maria hat geholfen

2013

Acrylic on cotton

30 × 40 cm

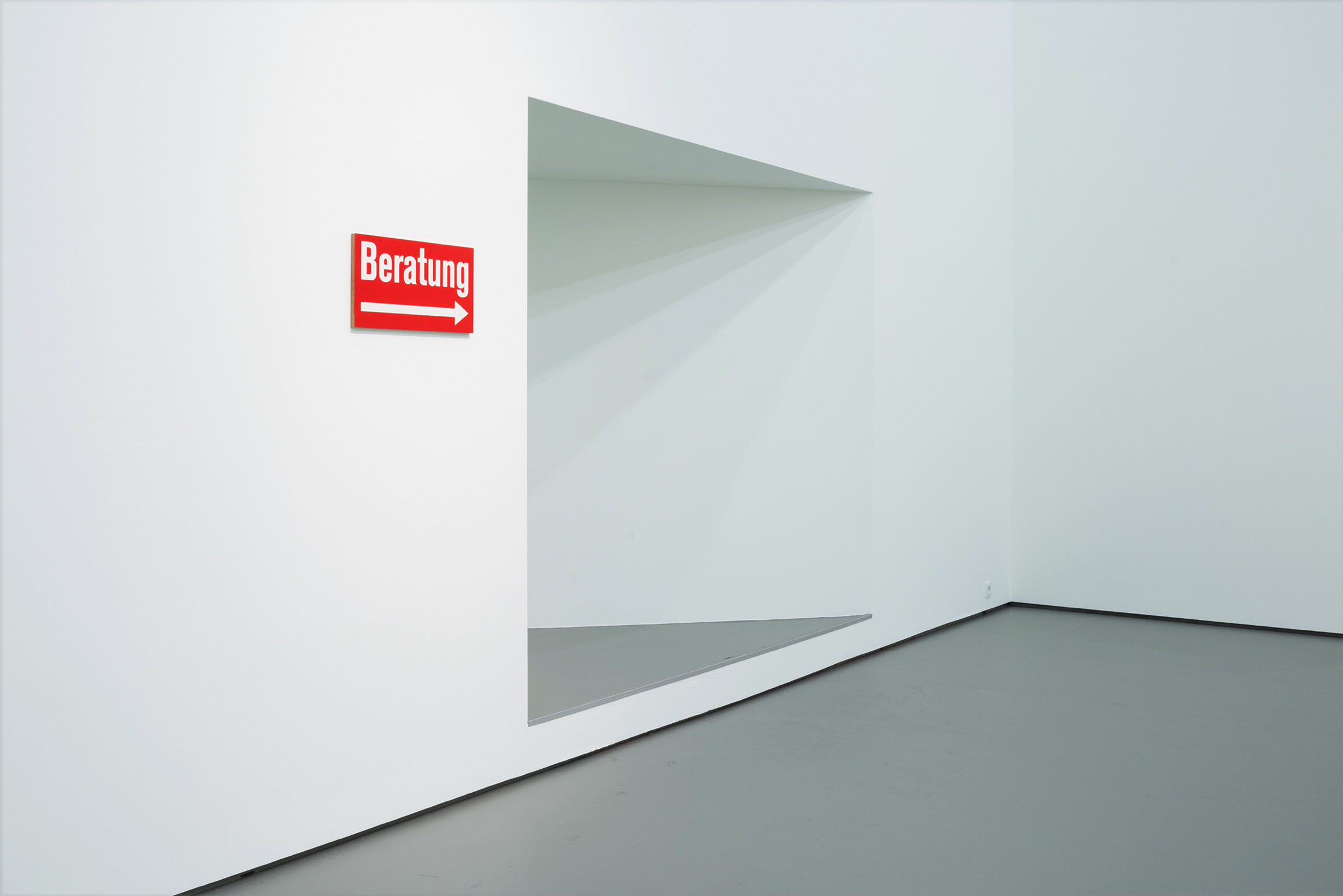

Beratung

2013

Acrylic and oil on cotton on MDF

27 × 51.5 cm

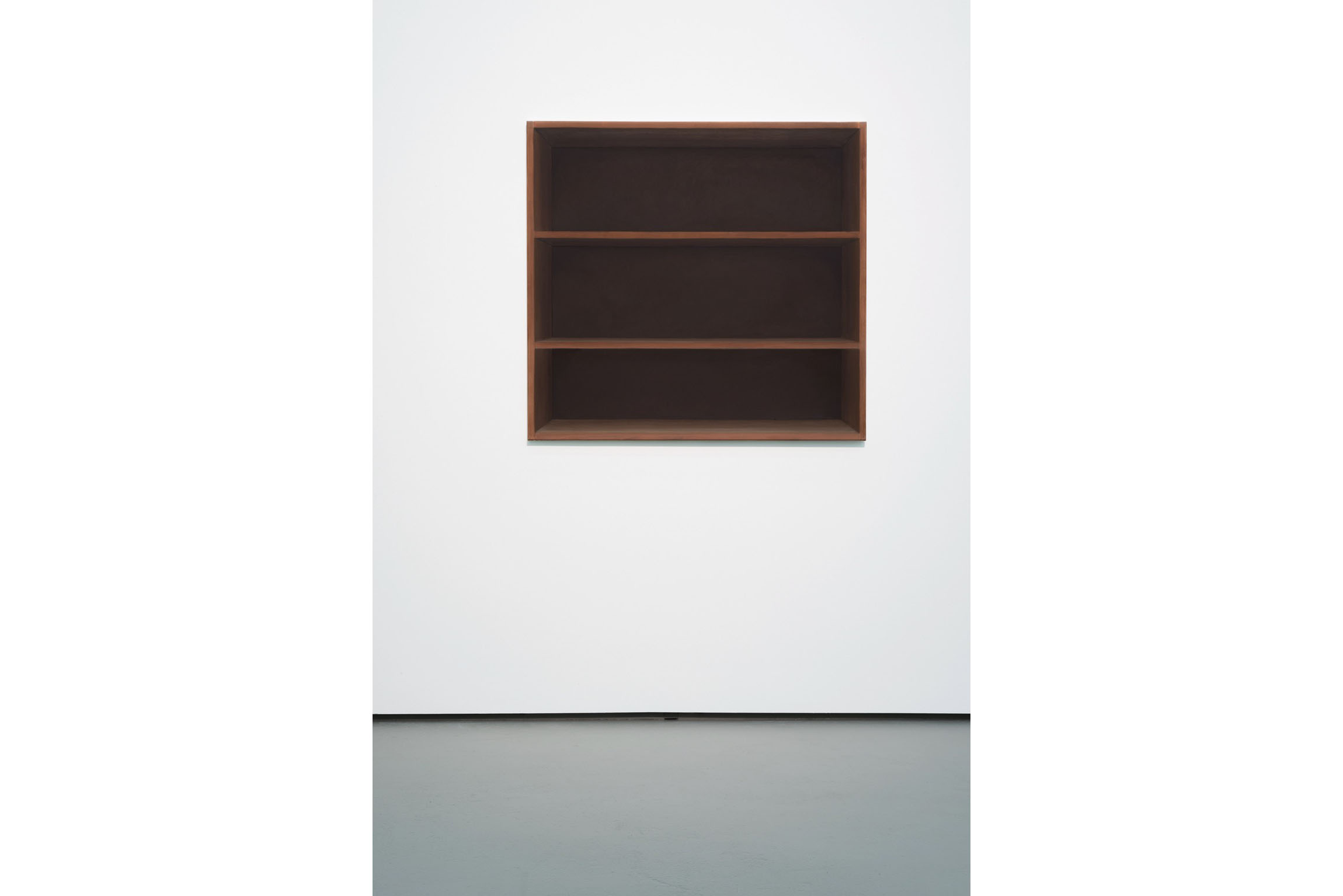

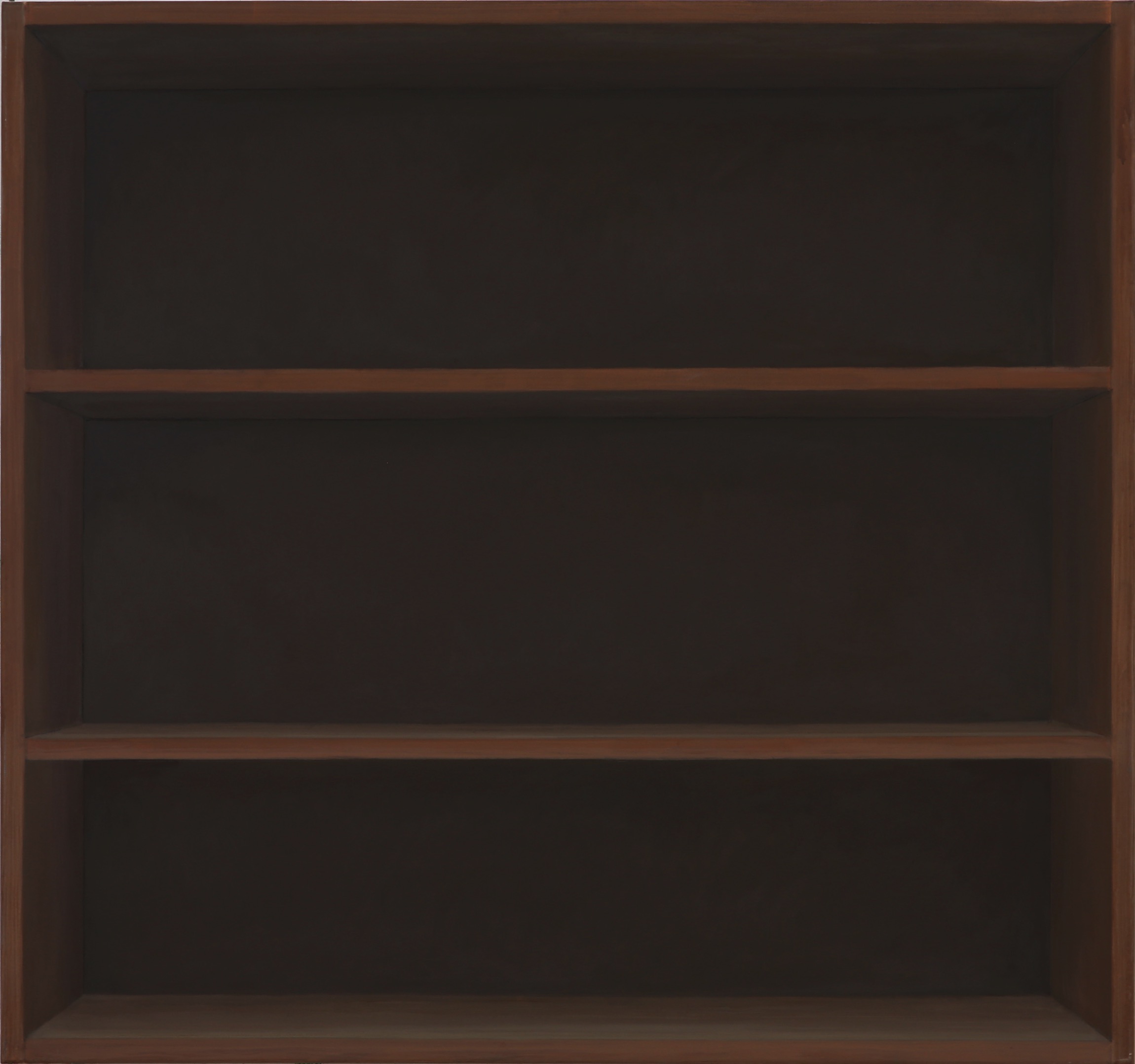

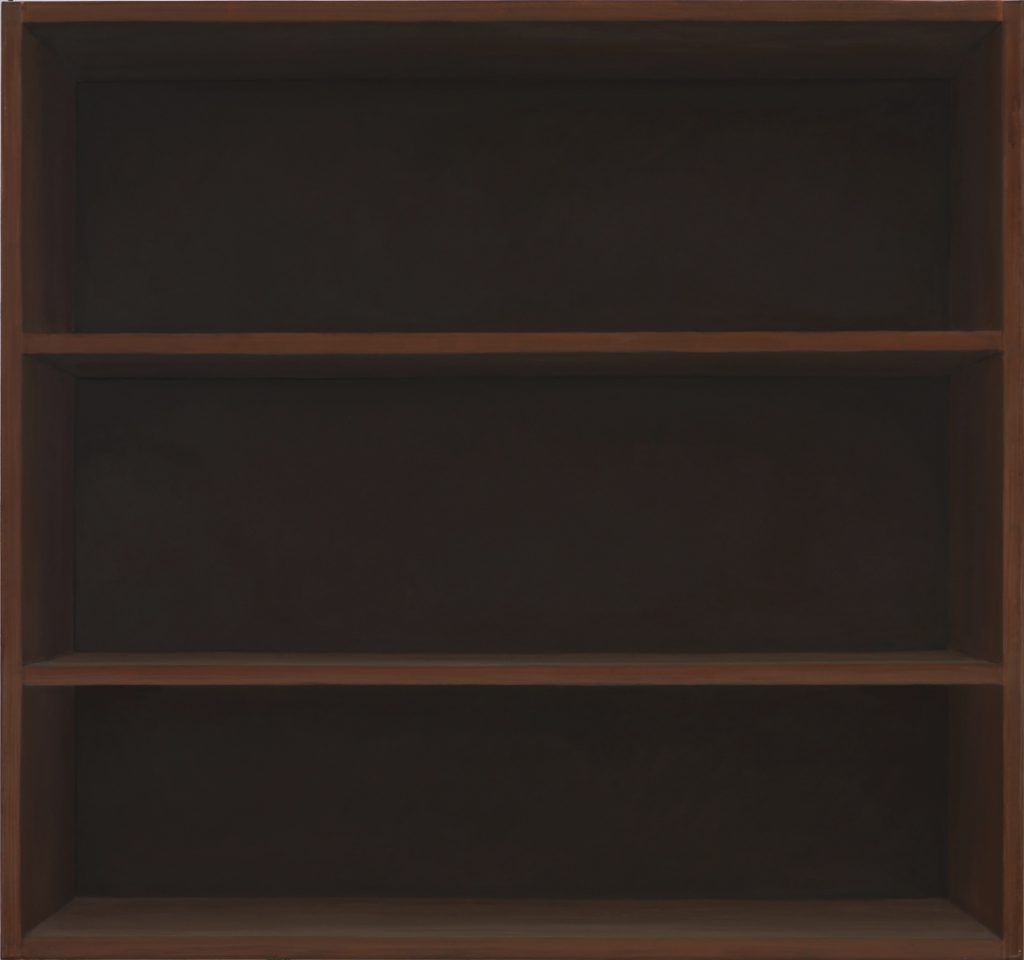

Tablare

2012

Acrylic on cotton

109 × 116 cm

Büro D. M.

2009

Acrylic and egg tempera on cotton

180 × 130 cm

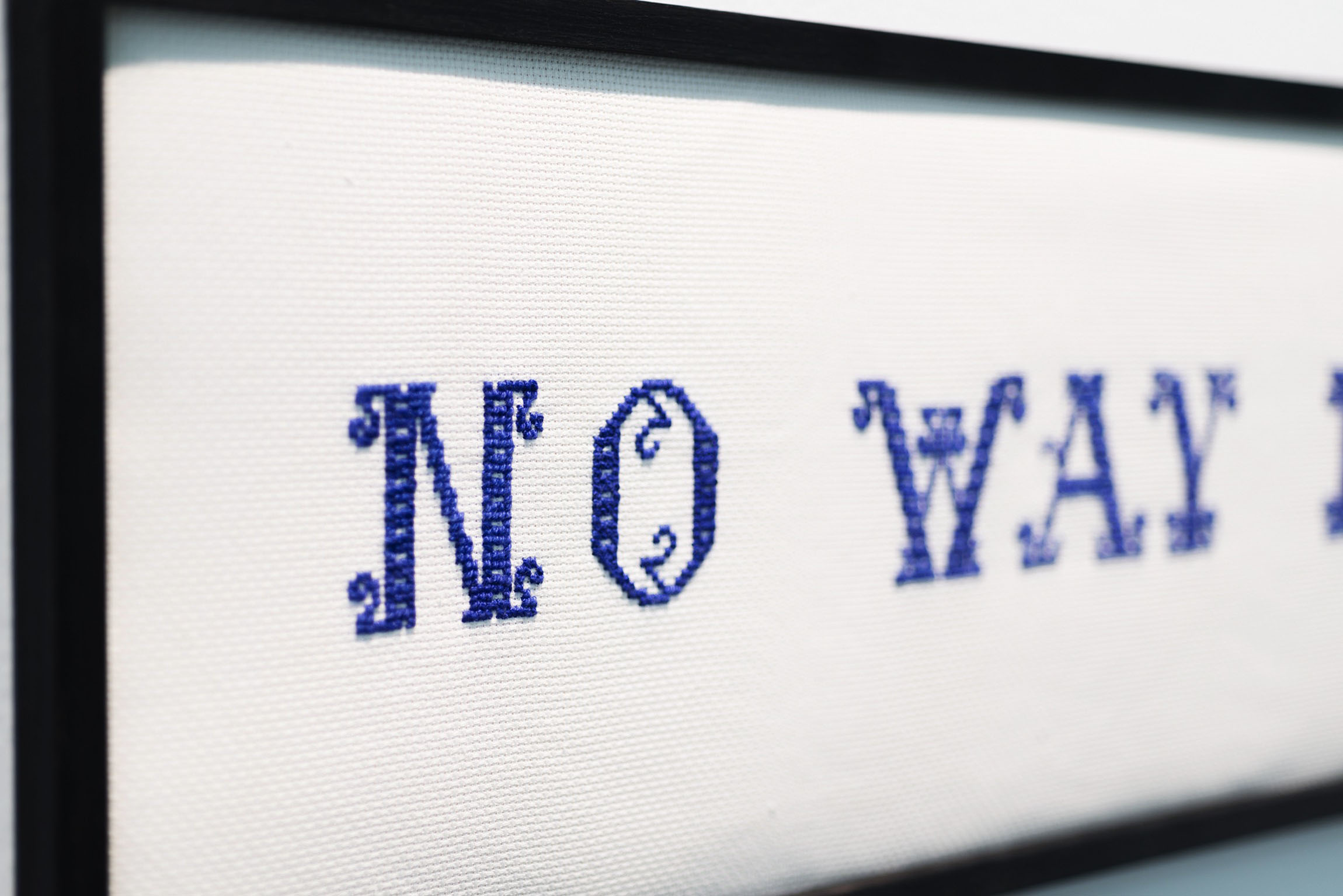

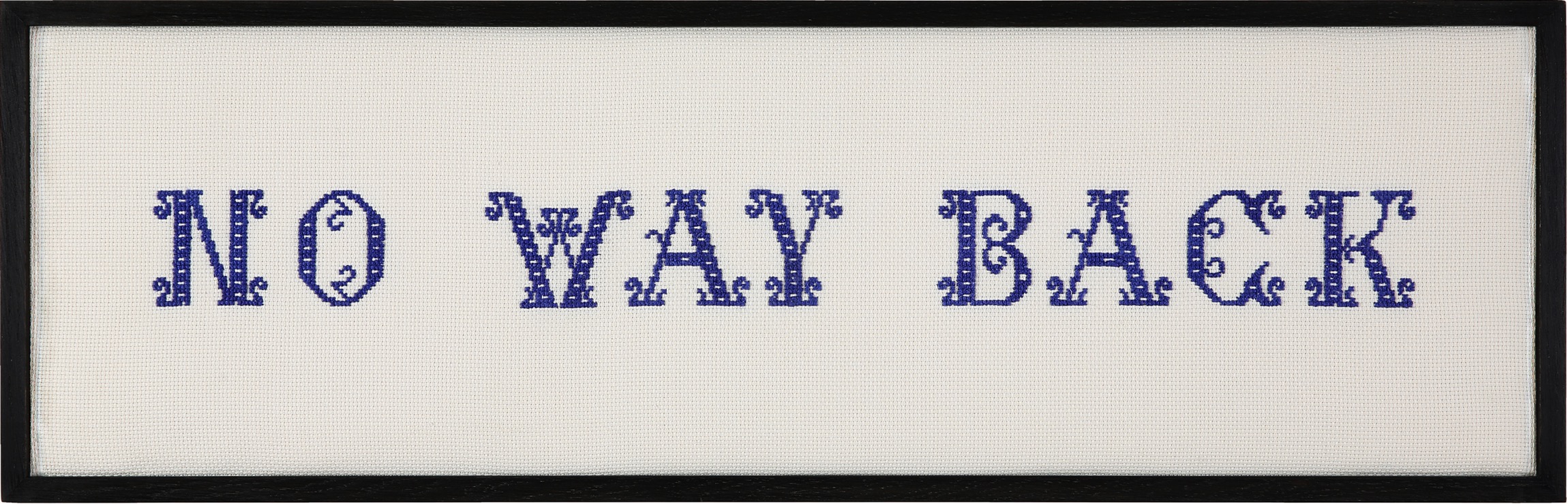

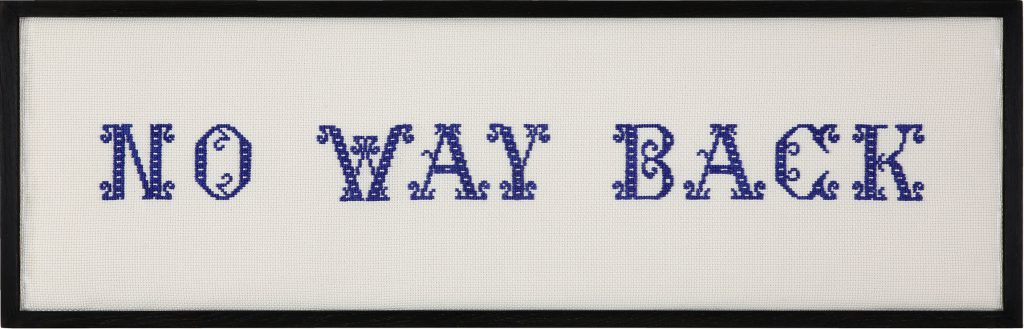

No Way Back

2014

Embroidery, artist’s frame

23 × 71.5 cm

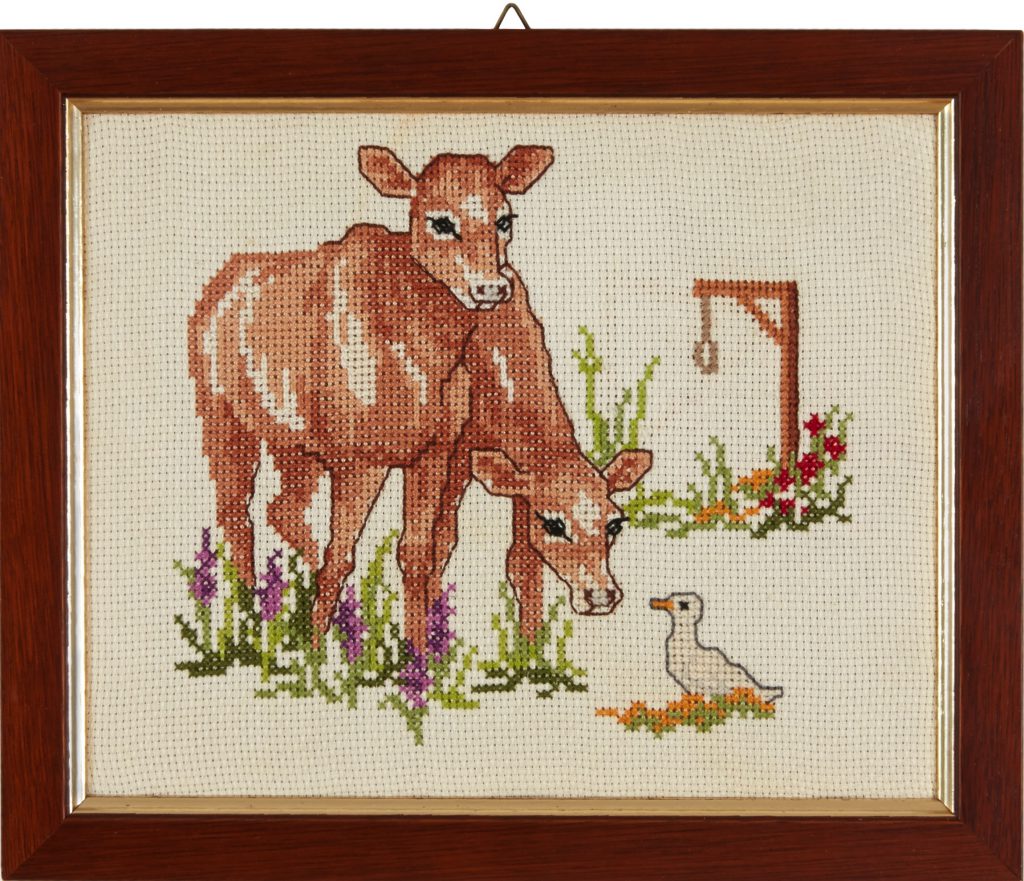

Untitled

1998/2008

Embroidery in artist’s frame

20 × 24 cm

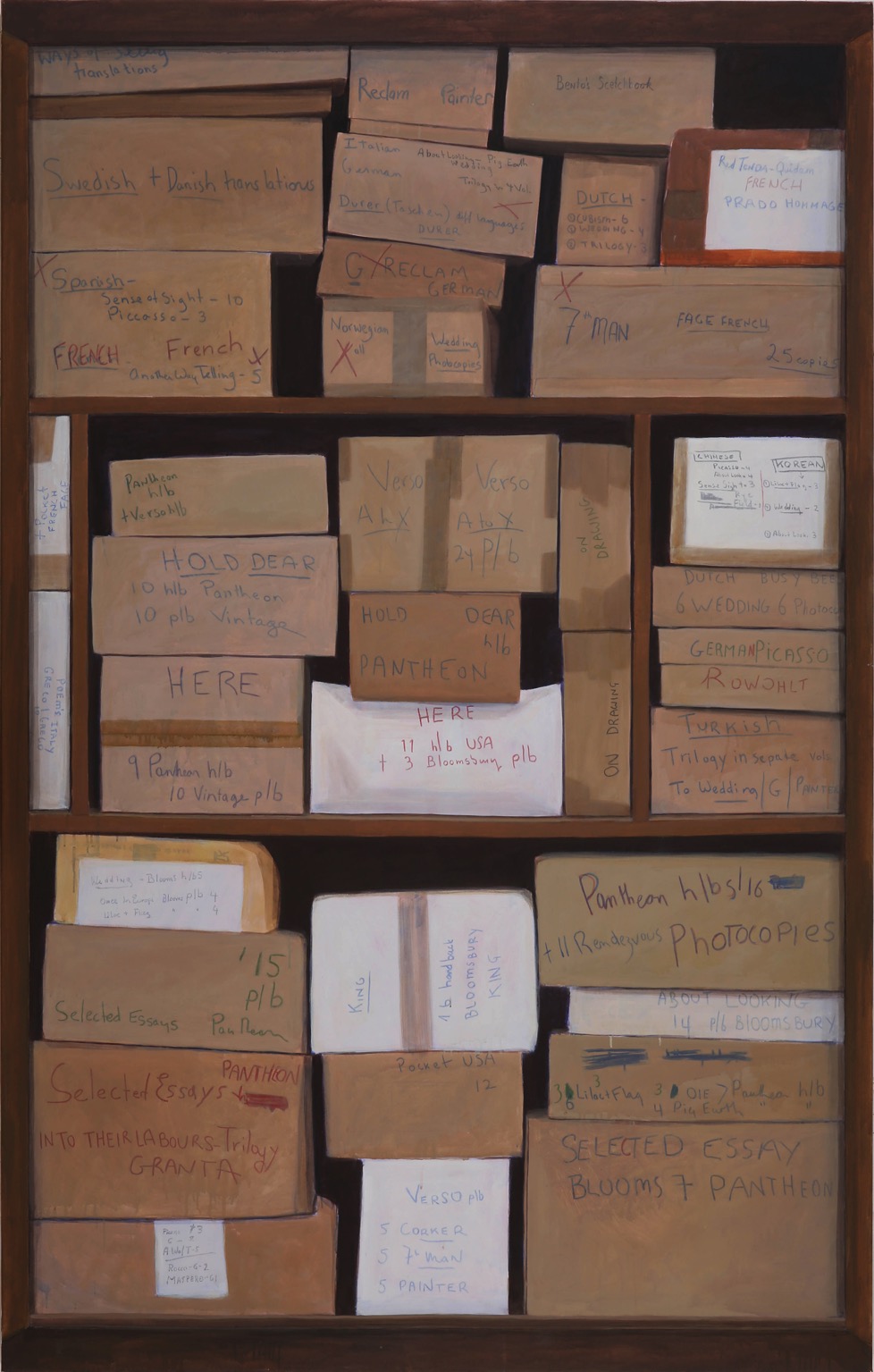

L’armoire dans la remise

2012

Acrylic on cotton

220 × 140 cm

Text

The mystery of Christoph Hänsli’s paintings was explained several years ago by writer John Berger, who described Hänsli’s Bedroom Paintings as unforgettable, although they do not convey any obvious sense of drama. “Or rather their drama, which is present in every square centimeter, is an invisible one,” he writes, speaking of the spectacular as palpably absent in Hänsli’s images. Even when he slices up an entire mortadella sausage and portrays both sides of each slice in oil and acrylic, the resulting 332 paintings appeal to our yearning for order and completeness more than aiming for effect. For several years Hänsli has been painting everyday objects and situations that are on the verge of extinction, and he has spared no technical pains in the process. Although the laconic manner of his work draws on Surrealism and Pop Art and is reminiscent of the works of Domenico Gnoli and Konrad Klapheck, it is ultimately more indebted to Conceptual Art. This is evinced by the artist’s decision to forego any hint of personal gesture when applying his superb painting technique, and by his rendering of everyday subject matter in life-sized scale. By thus “de-artifying” the image he enables the viewer to find an individual approach to the represented object, an approach rooted in personal memories.

A number of paintings in the exhibition “Stollen X” (Tunnel X), Hänsli’s second solo exhibition at Galerie Judin, offer re-encounters with themes that inspired earlier works. The artist has repeatedly stated that he does not seek out his subject matter. Following a chance encounter, an idea takes him mentally captive, in some cases for a period of several years, before he can express it in painting. Sometimes this then only provides partial release—and he is compelled to return to old subject matter. One could almost consider this a kind of artistic Stockholm syndrome. Hänsli himself describes it differently: “Life is not linear. Everything is connected with everything else—nothing is complete in and of itself.”

Continue reading

The largest painting in the exhibition is entitled Ofen Krematorium Nordheim (Furnace Crematorium Nordheim, 2012) and shows the exterior cladding of a modern incinerator with the opening to the combustion chamber. The form of this opening (which recalls a mouse hole in a cartoon) and the impenetrable black do not reveal whether the door is open or closed, thus recalling the painting of the switch “Türe auf/Türe zu” (Door Open/Door Closed) from our last Hänsli exhibition. This view of the furnace fascinated the artist due to its explicit flatness, which is only interrupted by the thin seams between the metal plates and tiny screws. Through the enormous subtlety of his brushwork Hänsli lends this surface a sensual quality, which one can only experience by examining the work at close range. Viewed from a distance, the painting is dominated by a sense of abstraction, which is enhanced by the reduced palette. Just as the delicately painted pepper corns convey the representative quality of the two-tone mortadella slices, in this later work the screws provide a key indicator of the concrete nature of the depicted. Incidentally, Hänsli’s obvious interest in sepulchral culture is rooted in his biography. A number of years ago he temporarily served as an “Expert for Cemetery and Gravestone Culture” for the City of Zurich.

Another large-format work, L’armoire dans la remise (The Cupboard in the Shed, 2012), bears witness to Hänsli’s deep interest in things that promise to create order. He found the motif for this image in the house of John Berger, who is quoted above. In the stacked and painstakingly labeled boxes are complimentary copies of the many publications of this journalist and author—an astounding accumulation of thoughts and words. Hänsli goes a step further with Tablare (Shelves, 2012). In this work, which is painted in a central perspective, there is a lack of ordered content. The viewer looks into an empty, very ordinary wooden shelf, which the artist discovered at his neighbor’s house. Having an obvious tendency towards organization, this neighbor—a nuclear physicist—had stored accumulated objects in identical wine cartons, which Hänsli replicated faithfully in the original version of this painting. However, the regularity of the vertical and horizontal lines of these boxes did not satisfy him, and so he experimented with painting over each box, one after the other. Hänsli does not show the shelf within its surrounding environment. Its external outlines are aligned with the edges of the painting, which makes it impossible to place the object in a context and reduces it simply to its function. Tablare, the image of an empty shelf, represents “the memory of an attempt to create order”—a phrase one often hears from Hänsli. Here it would be fitting to quote Oscar Wilde: “The true mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible.”

Signposts and inscriptions in public space have often served as a source of inspiration for Hänsli’s cryptic, small-format paintings. Maria hat geholfen (Maria Helped, 2013) is based on an embroidered votive image which the artist discovered in a pilgrim’s shrine during a hike through central Switzerland. He was fascinated not only by the strange, folk-art magic of such ex-voto images and the forthright depiction of human neediness, but also by its status as an image within an image, since the embroidery was presumably based on a drawing. The work Beratung (Consultation, 2013) belongs to the category of “absurd signage” (Hänsli). Experience has proven that the implied promise of receiving help and advice upon following the arrow is often a hollow one. Such signs usually represent the first skirmish—that takes place even before one faces off with an official—in a hopeless fight against bureaucracy. In contrast, No Way Back (2014) is disarmingly explicit. Hänsli encountered this sign, as we all have, in the transit area of an airport. It serves as a threat or a promise, depending on the circumstances of entry. This cynicism is luckily absent in the image All Off (2014). The artist found this label on the dashboard of a classic automobile, and he was charmed by the simple metaphor. How often does one wish for just this kind of button in a quandary! Hänsli discovered the signs that inspired the paintings Wahlschalter (Selector Switch) and Stollen X (Tunnel X), both dating from 2014, in a military fortification inside the Gotthard Pass. Carved from the granite stone with great effort during World War II, this branching system of tunnels and bunkers reflects the spirit of the “reduit”, the determined defense of the country from these strongholds. The remaining switches and signs bear witness to the attempt to create a sense of security or provide orientation in the dark passageways. One is thankful that All Off does not also stem from this bunker. Today the site serves as a museum. However, the spirit that spawned it has not yet vanished from Swiss minds.

A small group of display cases and box frames reveal Hänsli’s masterful ability to arrange objets trouvés. Over the years he has collected postcards—meanwhile owning over ten thousand. Working from this collection, he creates humorous pairings which he describes as Anthropologische Konstanten (Anthropological Constants, 2012). In the display case Besuchszeit (Visiting Hours, 2014) are little souvenir figures which have been arranged in a row up close to the glass —recalling the wives and accomplices of inmates during the weekly visiting hours. Despite the tackiness of the figurines, the small installation conveys a surprising degree of brutality. In the box frame Ohne Titel (Untitled, 2014) one finds old-fashioned portrait photographs in black and white showing three men and a woman of different generations. The viewer automatically attempts to discern a relationship between the people gazing earnestly into the camera. Hänsli plays with our common, inherent desire to create meaning and order.

Hänsli is currently working on an extensive series of portraits of screws. With an almost scientific degree of focus and a great passion for detail he paints (usually rusty) screws that he has found on streets and in parking lots in recent years. He is fascinated by the thought that every found screw is missing from somewhere. What could more perfectly illustrate Berger’s description of the “invisible drama” in Hänsli’s work?