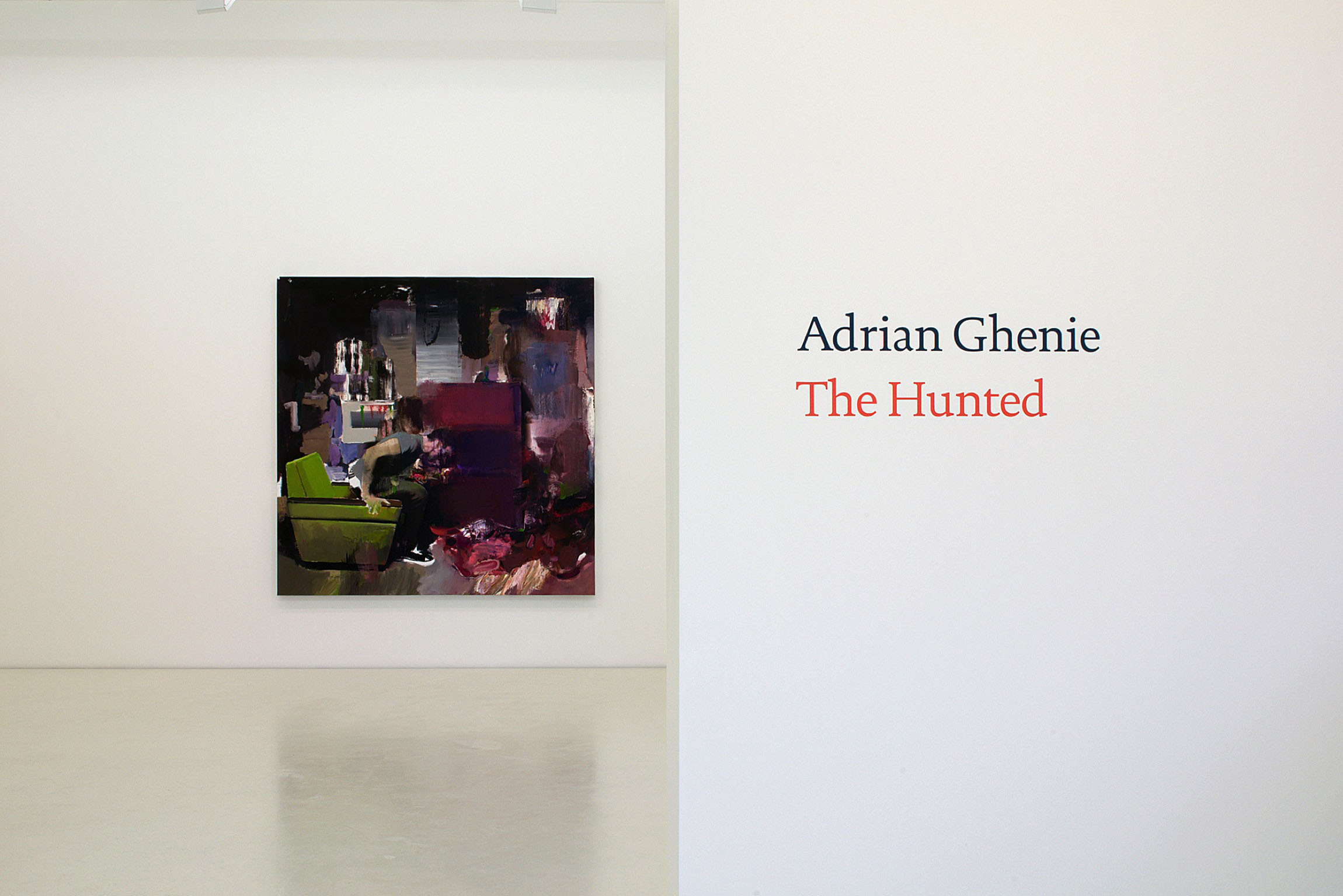

Adrian Ghenie

The Hunted

Works

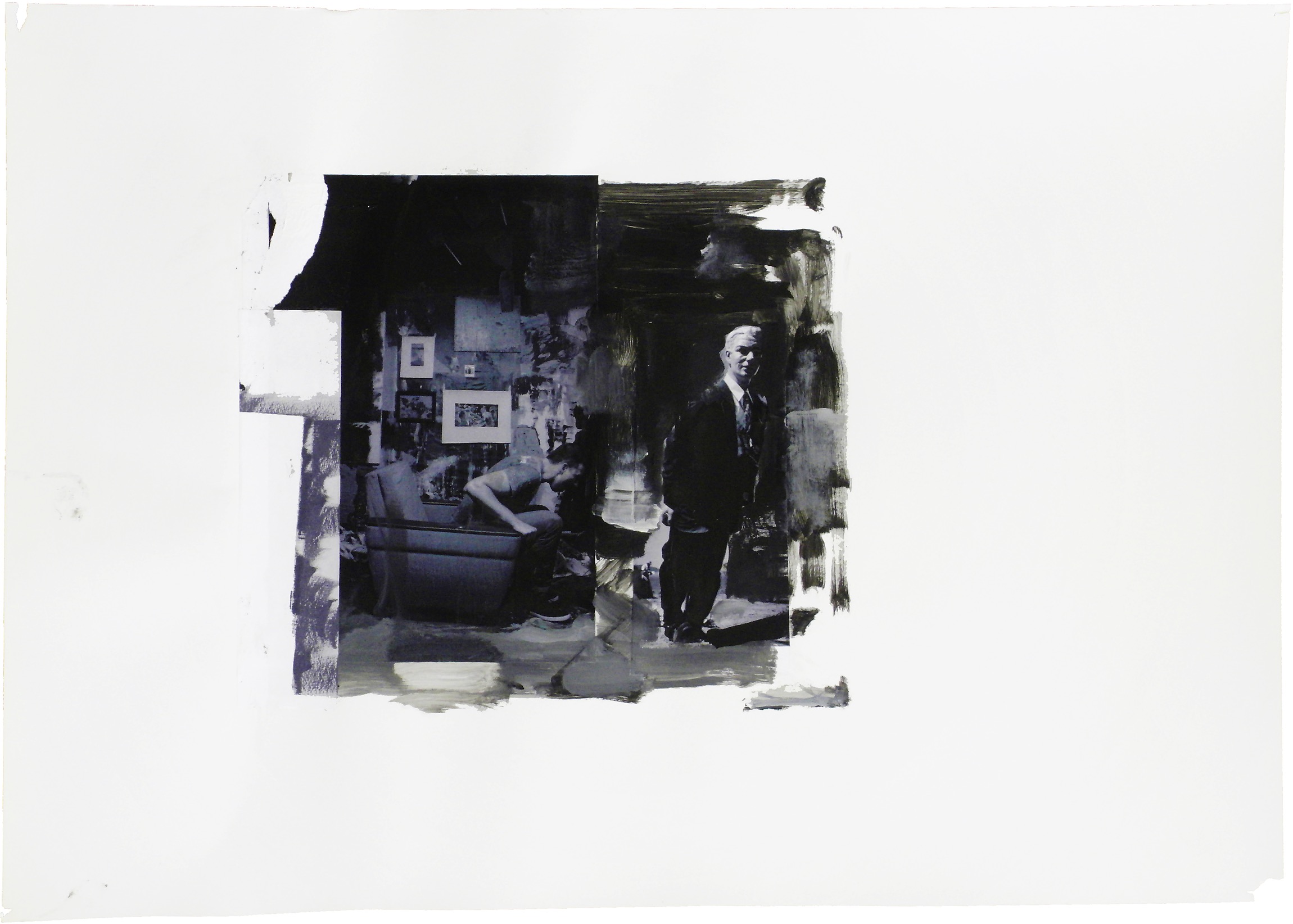

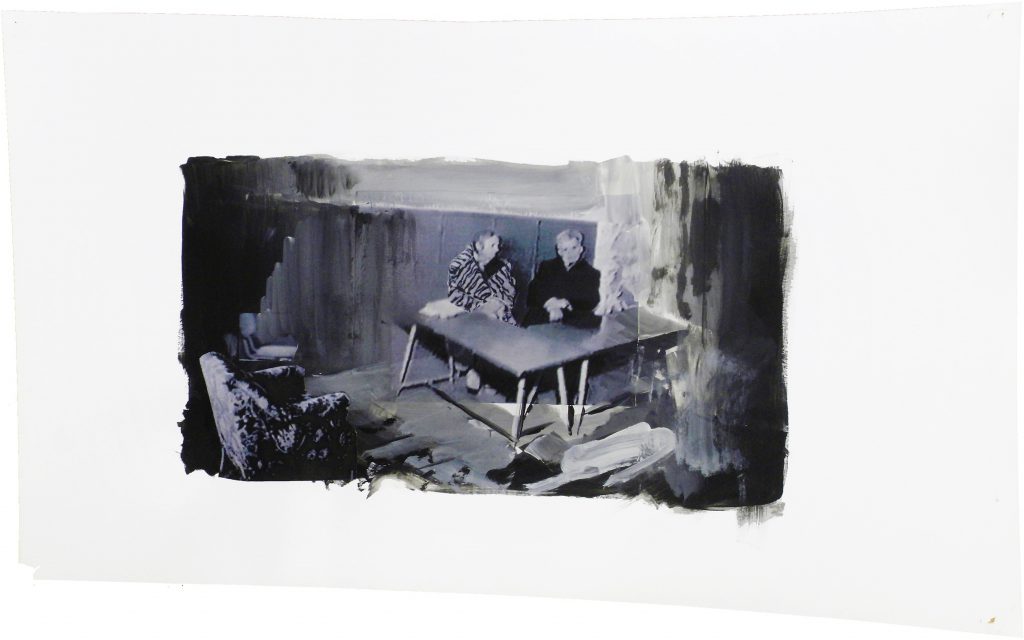

Study for “Boogeyman” (Detail)

2010

Collage and acrylic paint on paper

55 × 70 cm

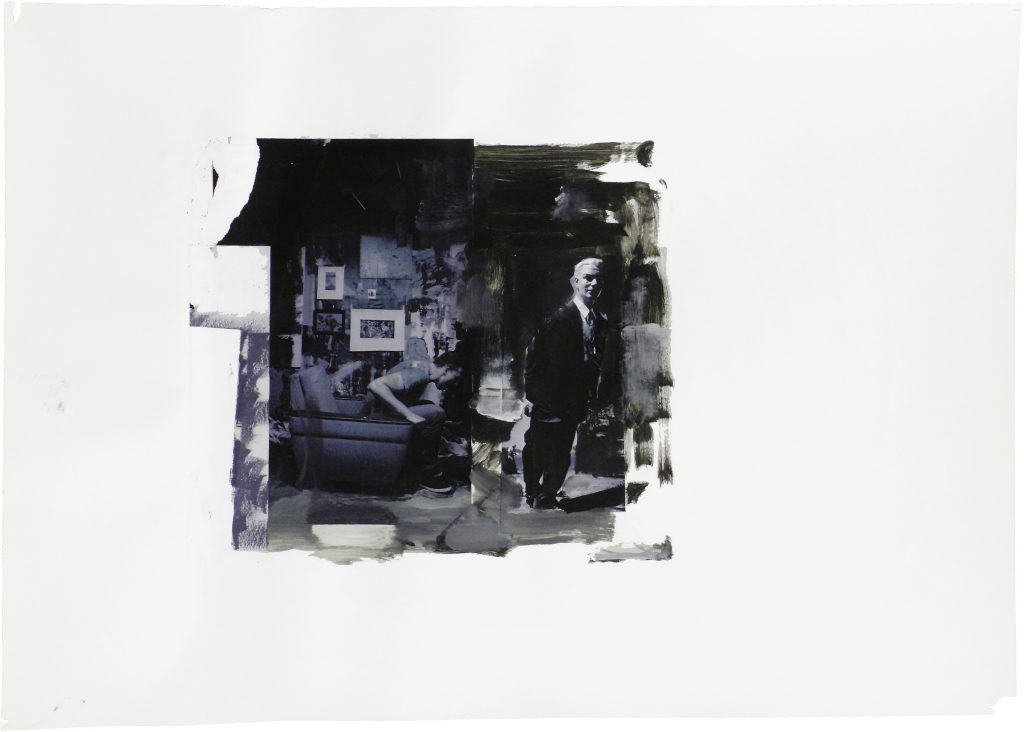

Study for “The Fake Rothko” (Detail)

2010

Collage and acrylic paint on paper

51 × 70 cm

Study for “The Devil” (Detail)

2010

Collage and acrylic paint on paper

51 × 70 cm

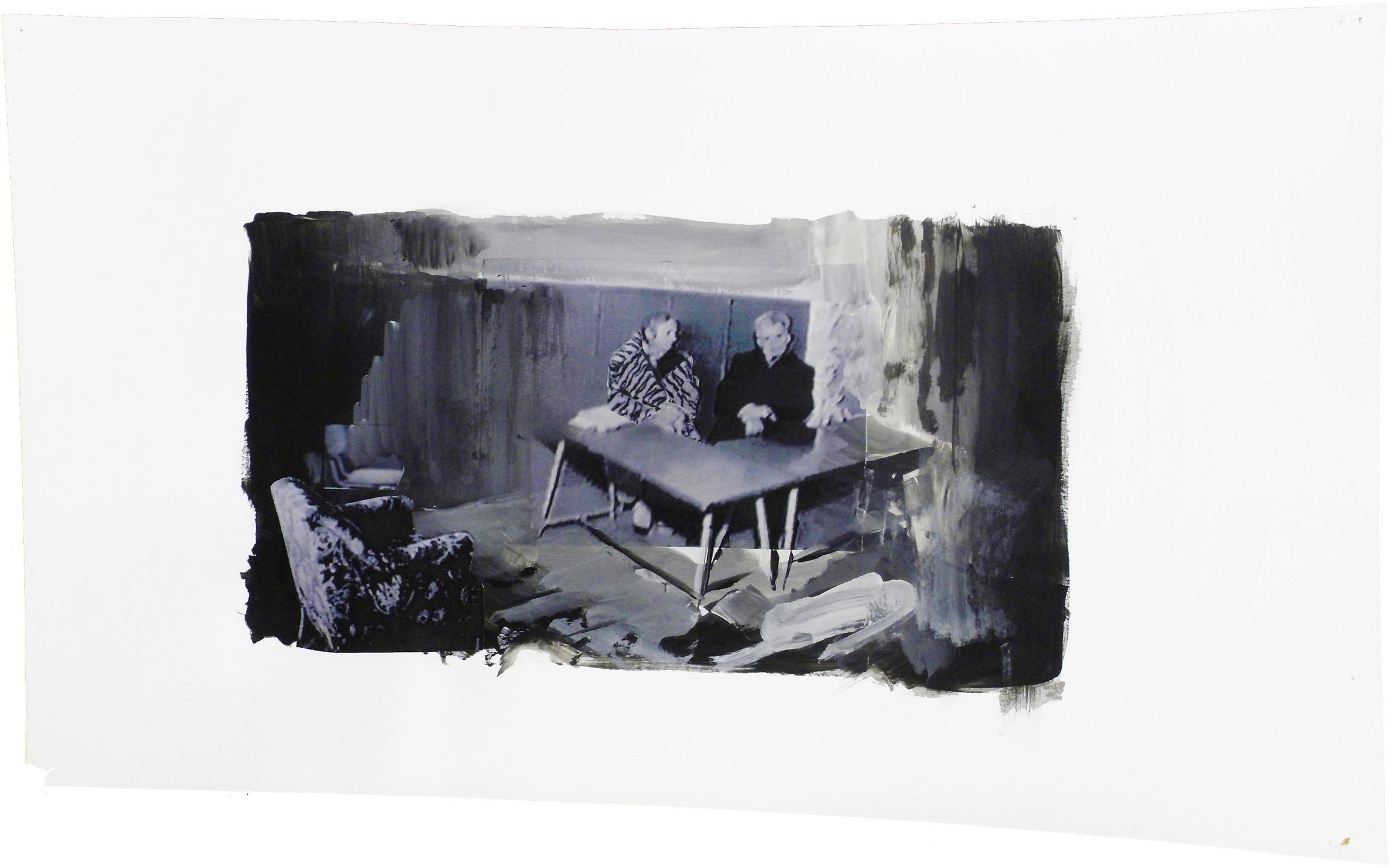

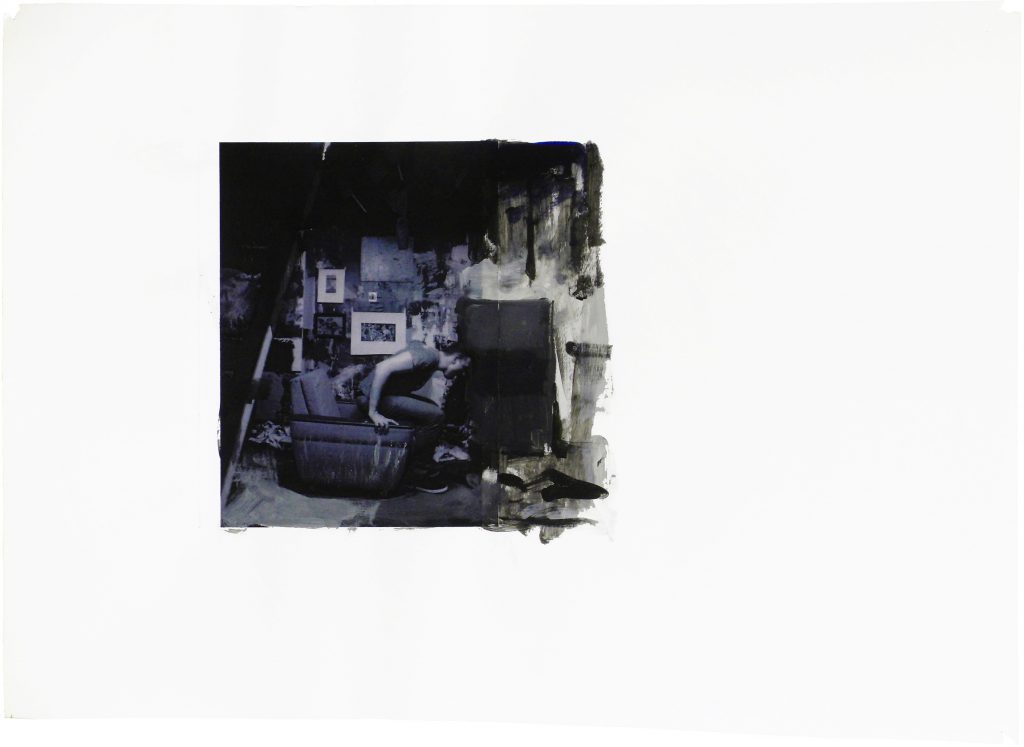

Study for “The Trial” (Detail)

2010

Collage and acrylic paint on paper

43.5 × 70 cm

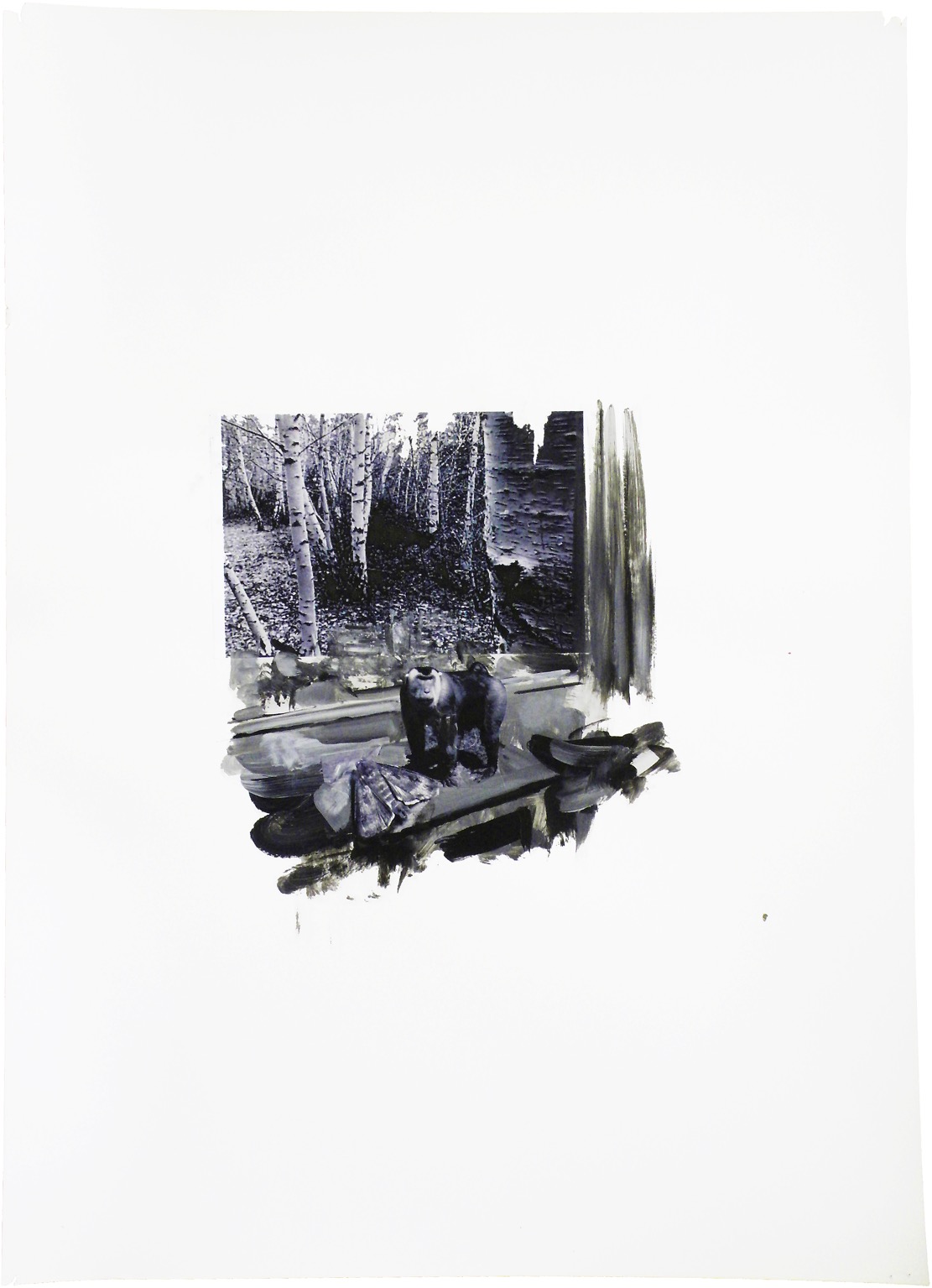

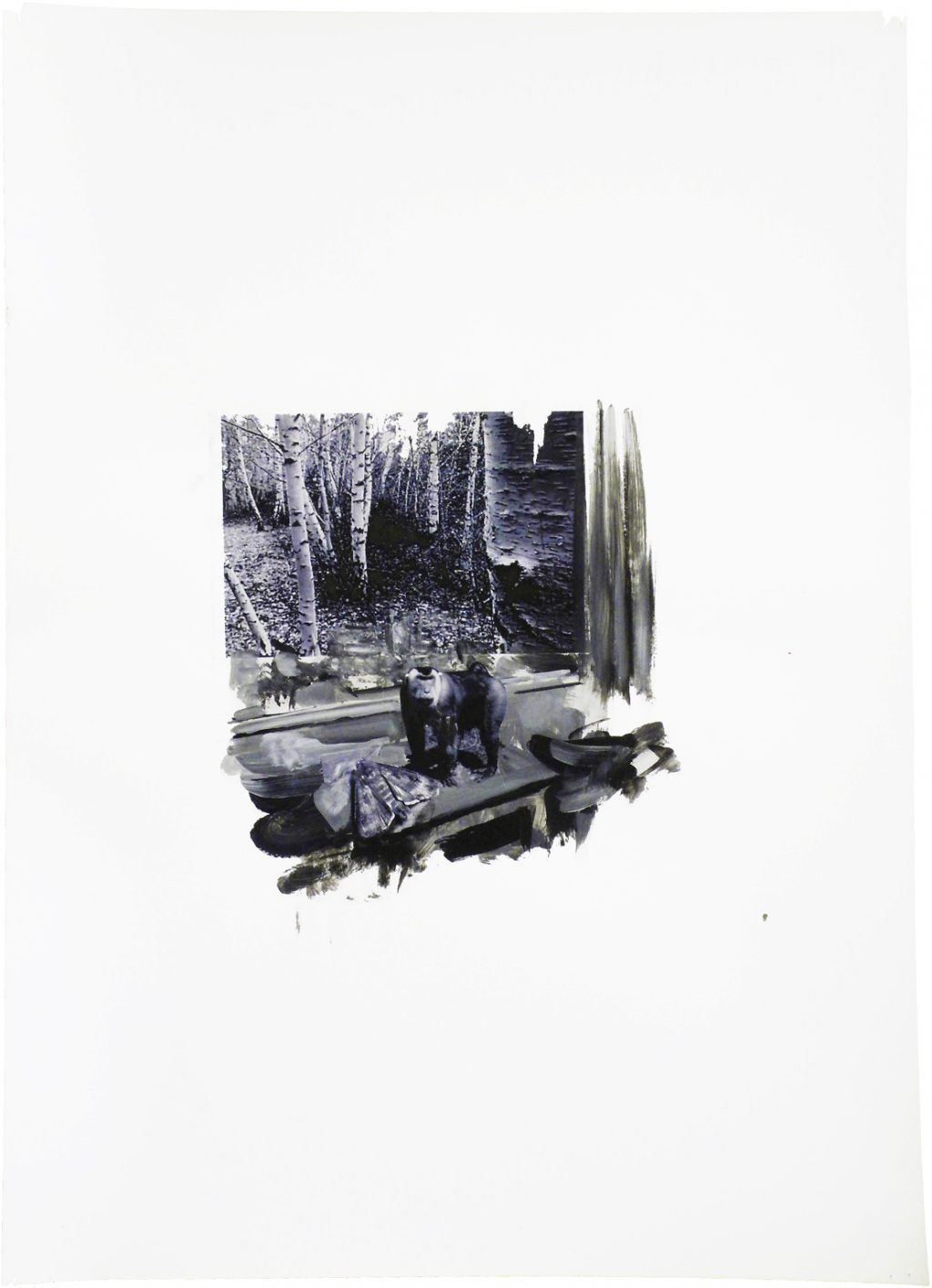

Study for “The Hunted” (Detail)

2010

Collage and acrylic paint on paper

70 × 51.5 cm

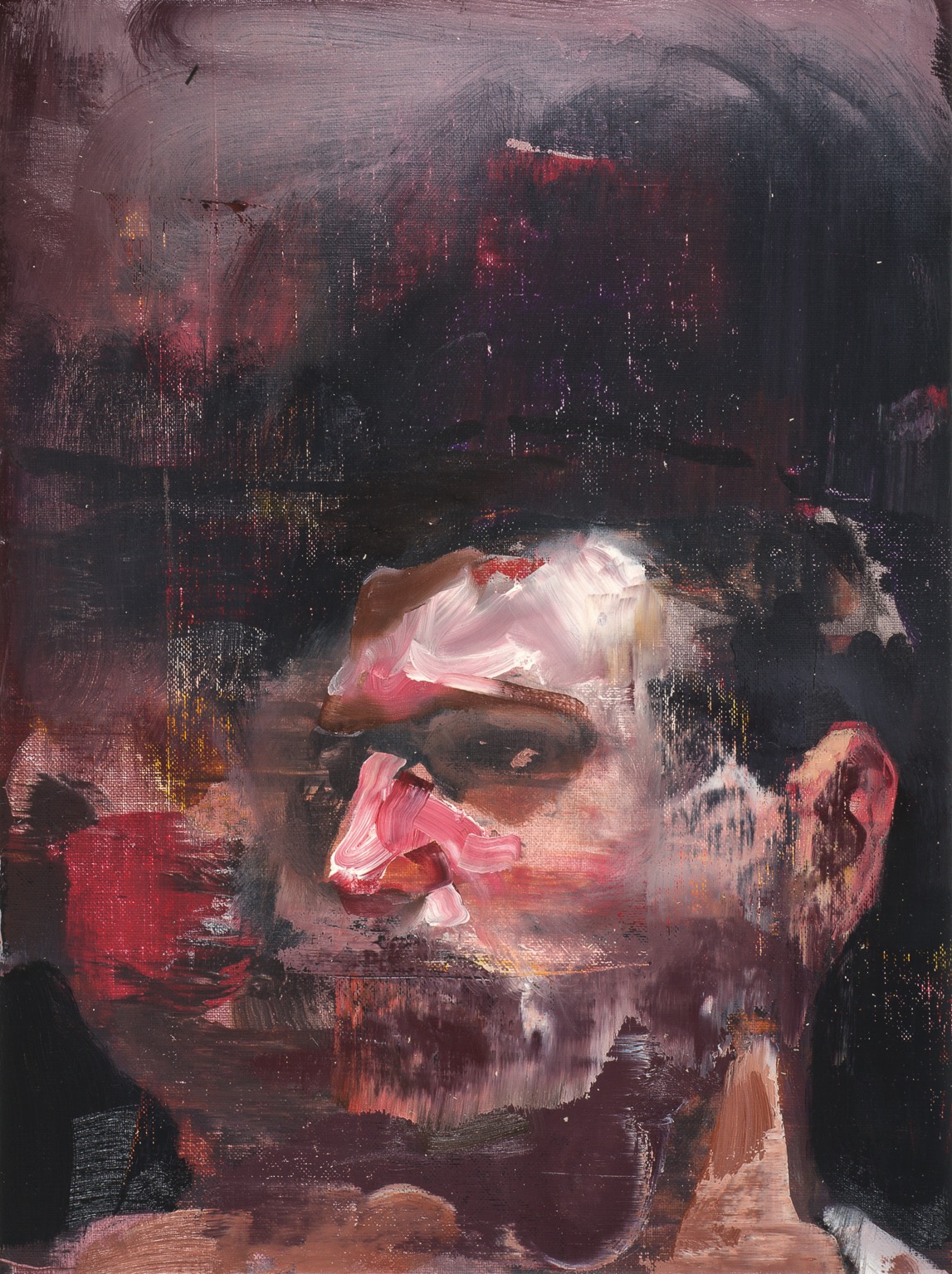

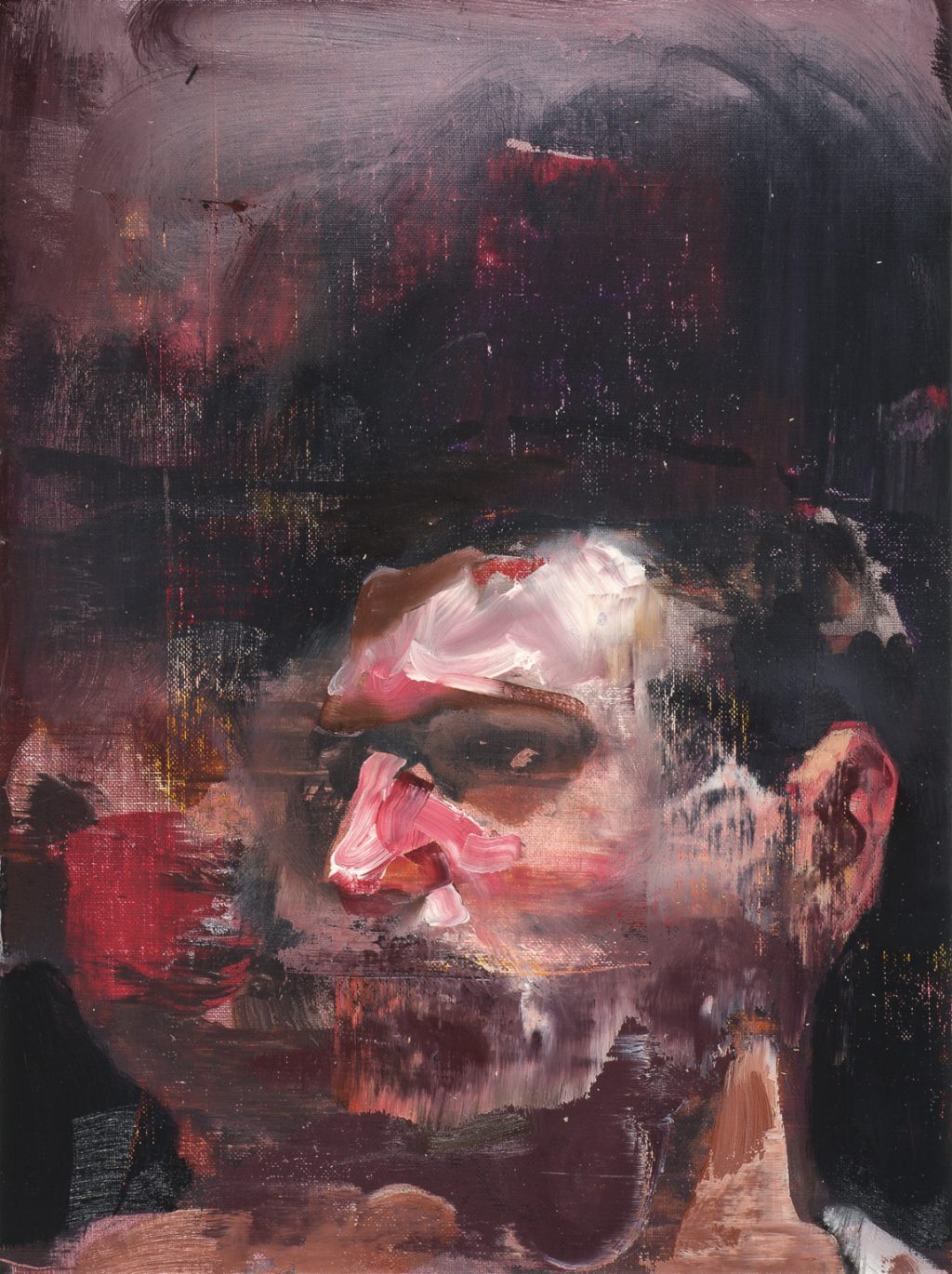

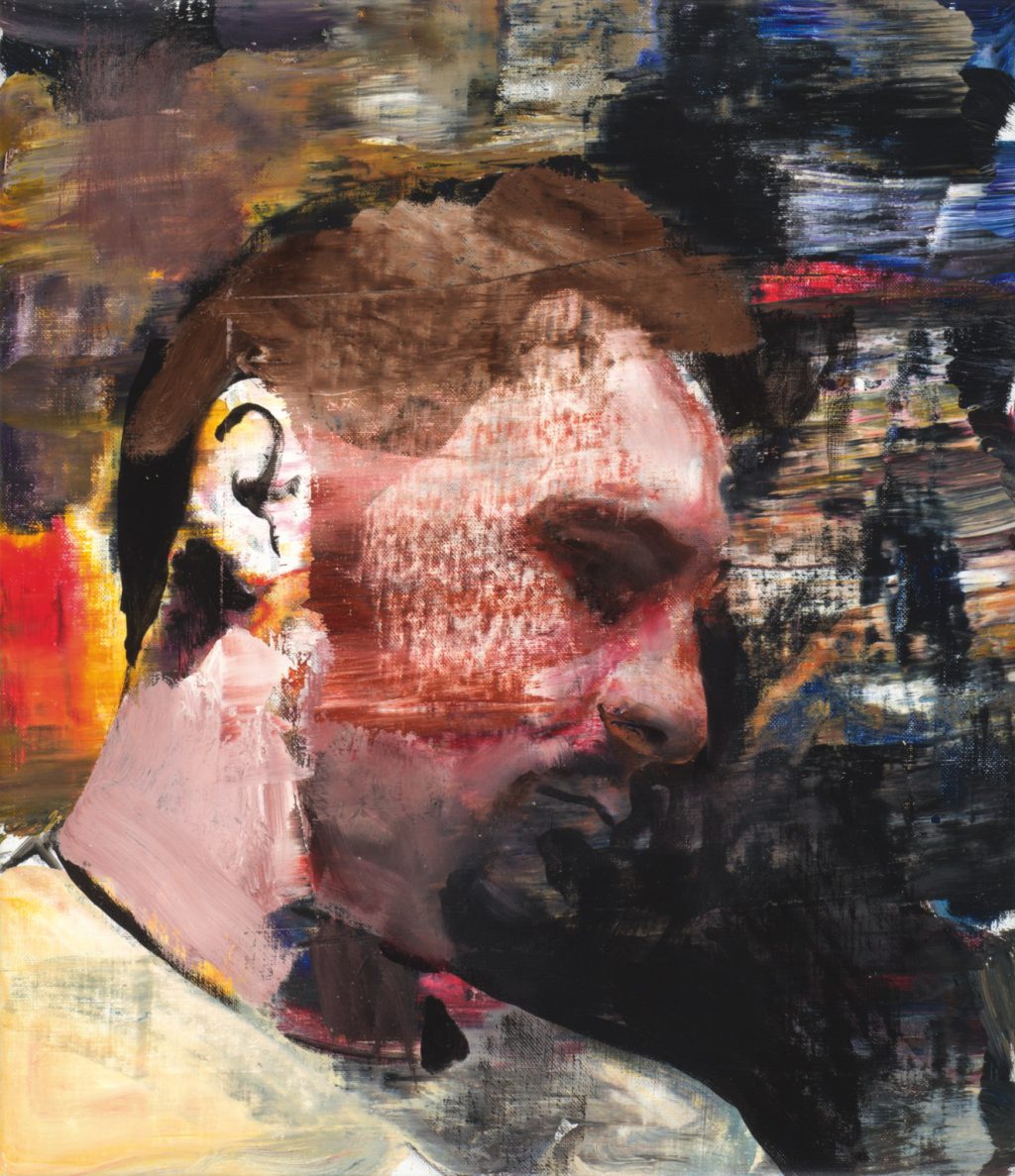

Self-Portrait No. 3

2010

Oil on canvas

46 × 34 cm

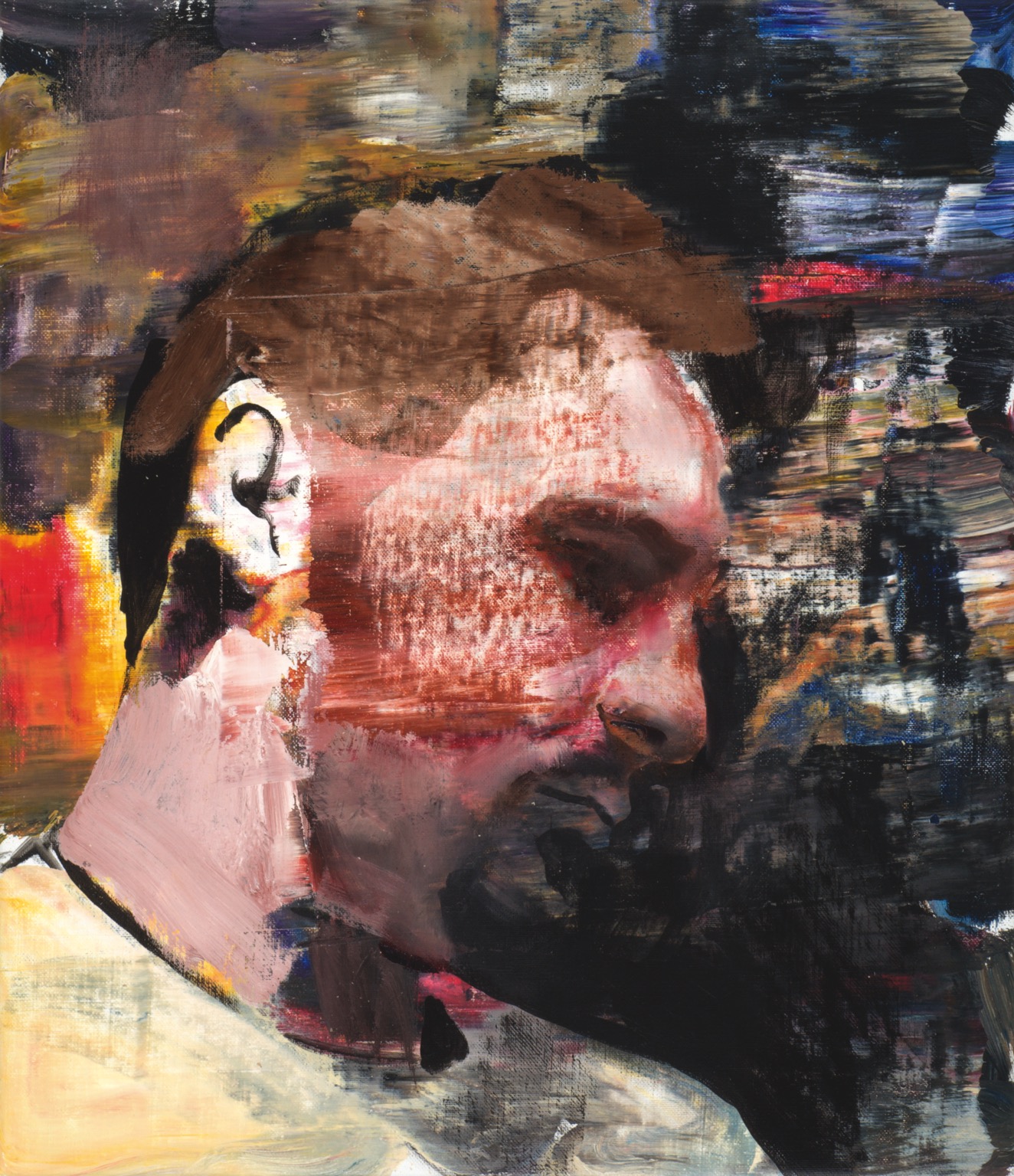

Self-Portrait No. 4

2010

Oil on canvas

51 × 43 cm

Nougat

2010

Oil on canvas

100 × 95 cm

The Moth

2010

Oil on canvas

50 × 38 cm

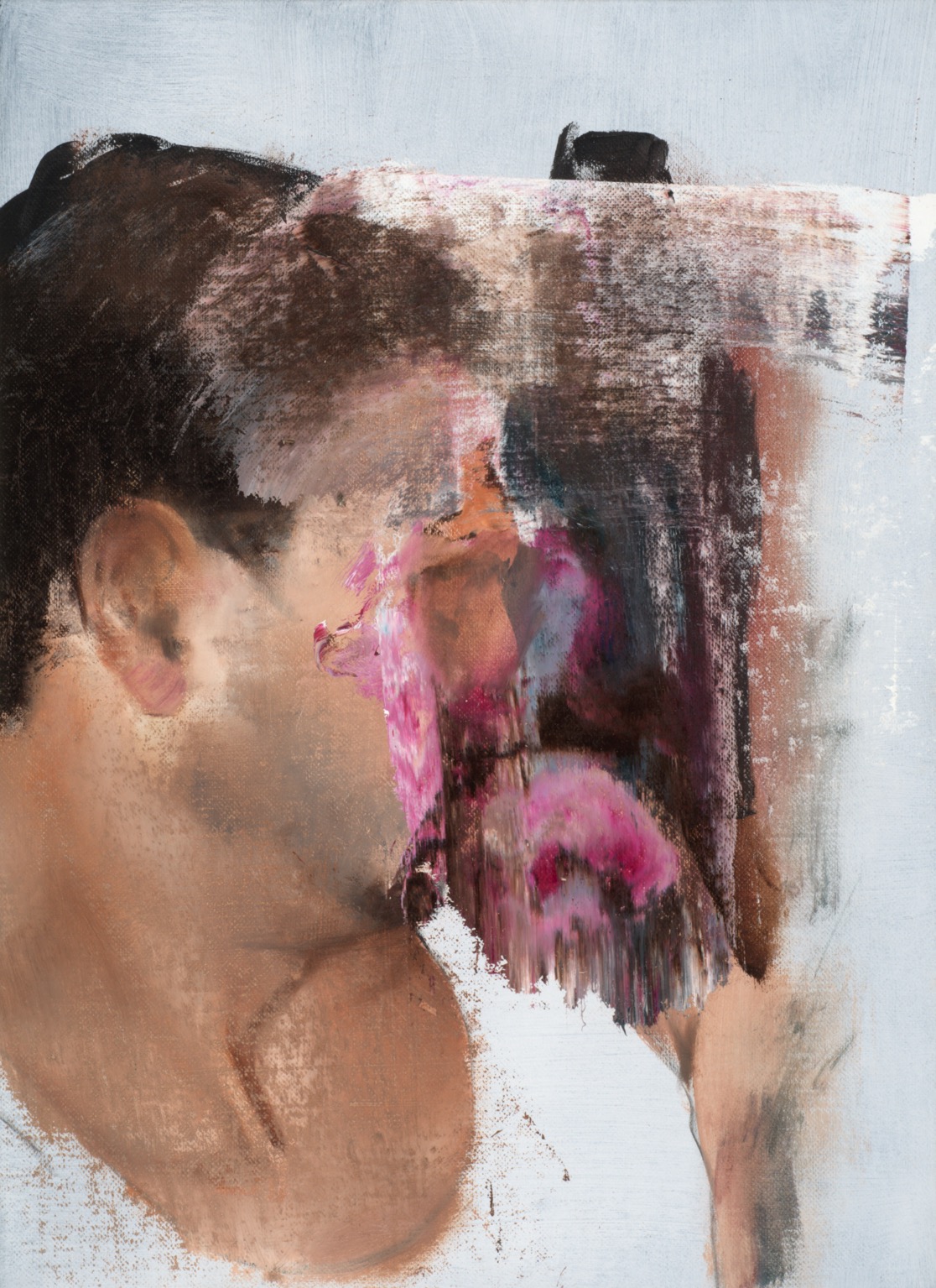

Self-Portrait No. 2

2010

Oil on canvas

52 × 38 cm

Study for “Boogeyman”

2010

Oil on canvas

50 × 40 cm

The Fake Rothko

2010

Oil on canvas

200 × 200 cm

Boogeyman

2010

Oil on canvas

200 × 335 cm

The Hunted

2010

Oil on canvas

203 × 170 cm

The Stigmata

2010

Oil on canvas

122 × 102 cm

About

In an exhibition entitled The Hunted, Nolan Judin Berlin is presenting ten new paintings by Romanian artist Adrian Ghenie, which he created after completing work in the spring of this year on his ambitious project, The Dada Room. And indeed, this ‘walk-in painting’, which will be shown for the first time in December in a retrospective exhibition at the SMAK in Ghent, makes a subtle appearance in one of the paintings of this new series. The working title Ghenie had given to these new paintings was The Visitation – not the first time that his titles evoke associations with Old Masters and refer to a range of topoi of art history. His last exhibition in these rooms was entitled The Flight into Egypt, but The Visitation is by no means a reference to yet another chapter in the life of the Virgin Mary, rich in apparitions and visitations though it was. The eerie experiences of Saint Anthony and his temptations come closer to the truth, for Ghenie is interested in the appearance of evil – more precisely: its visitation to the artist’s studio. Adrian Ghenie knows and appreciates his Old Masters, and his playful and confident use of art history is an important aspect of his work thus far. But rather than just citing art history, he makes original and multi-layered references to contemporary political and cultural themes, as well as to his own autobiography. In this he differs from other artists of his generation, whose usage of the enormous wealth of art history rarely goes beyond an ironic stance.

Engaging with Ghenie’s compositions, we quickly notice that our artist is not (only) being visited by evil in the familiar shape of the ‘devil’ who seeks to lead him astray from the path of virtue. The best example of this is the painting The Fake Rothko: standing behind a seated figure that we easily recognise as Ghenie himself, we see a glorious Rothko painting, one of the sort every auction house would consider the highlight of an evening sale. The blurred blocks of luminescent colours, so typical of Rothko, enhance the impression that the painting itself is an apparition. But where lies the evil in a painting by the great abstract master? Is the artist considering the forgery of such a painting? This is at least what the title suggests. Or is he thinking of the millions that Rothko’s paintings fetch in today’s market? Or is Ghenie preoccupied with Rothko’s own fate, who having succumbed to the demons of his depressions, took his life in 1970 (in his own studio)? Still, none of these interpretations explain why the artist in the painting seems to be vomiting. Incidentally, the wall against which the Rothko painting is leaning is taken from Ghenie’s The Dada Room.

Continue reading

The painting that lent its title to the exhibition is equally mysterious and ambiguous. The first thing we see in The Hunted is a monkey sitting on a low table in front of a forest landscape. Upon closer inspection we perceive a giant moth lying on the table next to the monkey – and recognise that the apparent forest is just one of those ‘photo-wallpapers’, popular in the 1970s but luckily extinct today. The seemingly straightforward title leaves open the question of who is being ‘hunted’ here. The monkey might have been chasing the moth, but could just as well be a hunted and stuffed sample of his species. Furthermore, both animals can personify evil. Since the Middle Ages, the monkey has been a symbol of both the fallen angel and the defeated devil – of, that is, the demonic as such. The moth cannot but remind us of the poster for ‘The Silence of the Lambs’ – to this day one of the best movies dealing with the phenomenon of evil. In The Hunted, the animals and the scenery surrounding them are incongruous in an irritating way. The African baboon does not fit the Scandinavian birch forest, nor does the oversized moth fit the small table. In his painting Dada is Dead (2009), Ghenie sends a wolf straying through the rooms of Berlin’s legendary Dada Salon. He loves presenting the viewer with such surprising constellations – a kind of surrealist greeting from afar! As often, The Hunted, too, contains an autobiographical element: Ghenie remembers these photo-wallpapers from his youth in Communist Romania. Back then, they were popular status symbols, because they had to be acquired from abroad.

In Boogeyman, the largest painting in the series, evil does seem to take on human form after all. The term itself refers to a creature or thing that causes someone irrational fear (“…or the boogeyman will get you!”). The seated figure in the painting, however – the painter himself – does not show any signs of fear. Instead, he seems to be listening to the dark visitor, his gaze focused on the chaos of shapes and colours in the studio’s background. In the mysterious figure’s roughly scraped facial features, we recognise Pan, the mythological half-man, half-animal. In ancient times the symbol of music and revelry, in Christianity he came to acquire a negative meaning. Horned and cloven-hoofed, he became the visual inspiration for the devil. In “Dr. Faustus”, Thomas Mann lets composer Leverkühn sign a deal with the devil: 24 years of inspiration and creativity – in exchange for renouncing love. Surely, the dream of never-ending creative power is something that a 21st-century artist, too, might give some thought. It may be coincidence that Mann’s composer Leverkühn is called Adrian. In any case, the title Boogeyman is certainly ironic.

Two small portraits fit seamlessly into the Visitation series. In The Moth, the large insect from The Hunted has landed on Stalin’s forehead. Ghenie’s fascination with Eastern European dictators has already produced a series of studies of Lenin, as well as the series The Trial, which deals with the last hours in the lives of the toppled Romanian ruler Ceausescu and his wife. The exhumation of Ceausescu’s body and the publication of images of his remains earlier this year inspired Ghenie to paint Study for the Boogeyman. But the dictator did not make it into the larger painting.

Self-Portrait No. 2 is only the second time that the artist has made himself the subject of a portrait, although this painting is more of a virtuoso colour-study of his neck and jaw. Like in the other two self-portraits and the depictions of the dictators, the anatomical details that constitute a face – eyes, nose, mouth – are mostly blurred and painted over, while the lateral features are depicted in a naturalistic and plastic manner. As a portraitist, Ghenie is a painter of heads, not faces – and the difference between the two matters: “For the face is a structured, spatial organisation that conceals the head, whereas the head is dependent upon the body, even if it is the point of the body, its culmination.” (Gilles Deleuze). Like Francis Bacon before him, Ghenie dismantles the face in order to discover the head that lies beneath.

The most recent painting in the exhibition, The Stigmata, is not part of the Visitation series, but it gives us a taste of the next group of works that Ghenie will be turning to. The composition is based on photographs of nuclear weapons tests conducted by the US military in the Nevada desert in 1951. Although nuclear ‘mushroom clouds’ appear in Ghenie’s paintings already in 2006, his interest does not lie with the explosions or their aftermath. The task he has set for himself is rather to depict the dryness and ruggedness as they appear in the landscapes of the early Renaissance-masters Piero della Francesca and Antonella da Messina. Ghenie is fascinated by the abstractness and modernity of these painted rock formations. In the right foreground of The Stigmata he has included the rock that dominates Jan van Eyck’s masterpiece Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (1438). But the choice of title for this landscape study is more than just an art-historical reference. The Greek word ‘stigma’ can also be translated as a ‘burn mark’ – and what does the explosion of a nuclear bomb inflict on a landscape if not an enormous burn mark? It bears mentioning that The Stigmata and the related study Nougat (the codename of a nuclear test) are the most light-filled paintings that Ghenie has ever painted. They might well be a turning point. [JJ]