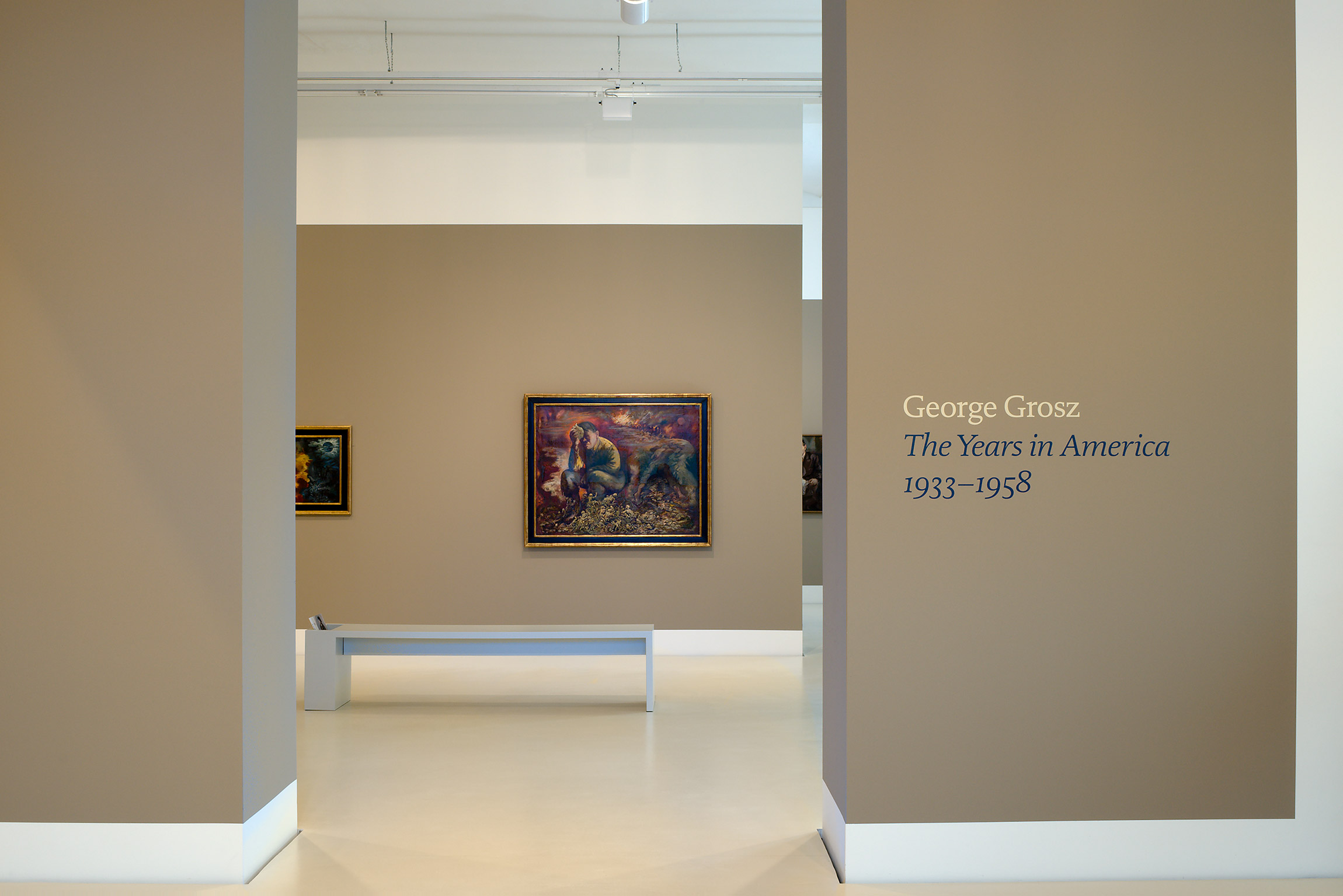

George Grosz

The Years in America 1933–1958

Works

This is a Man?

ca. 1957

Collage on paper on cardboard

48.6 × 37 cm

The Painter of the Hole II

1950

Oil on high-density fiberboard

71.2 × 50.9 cm

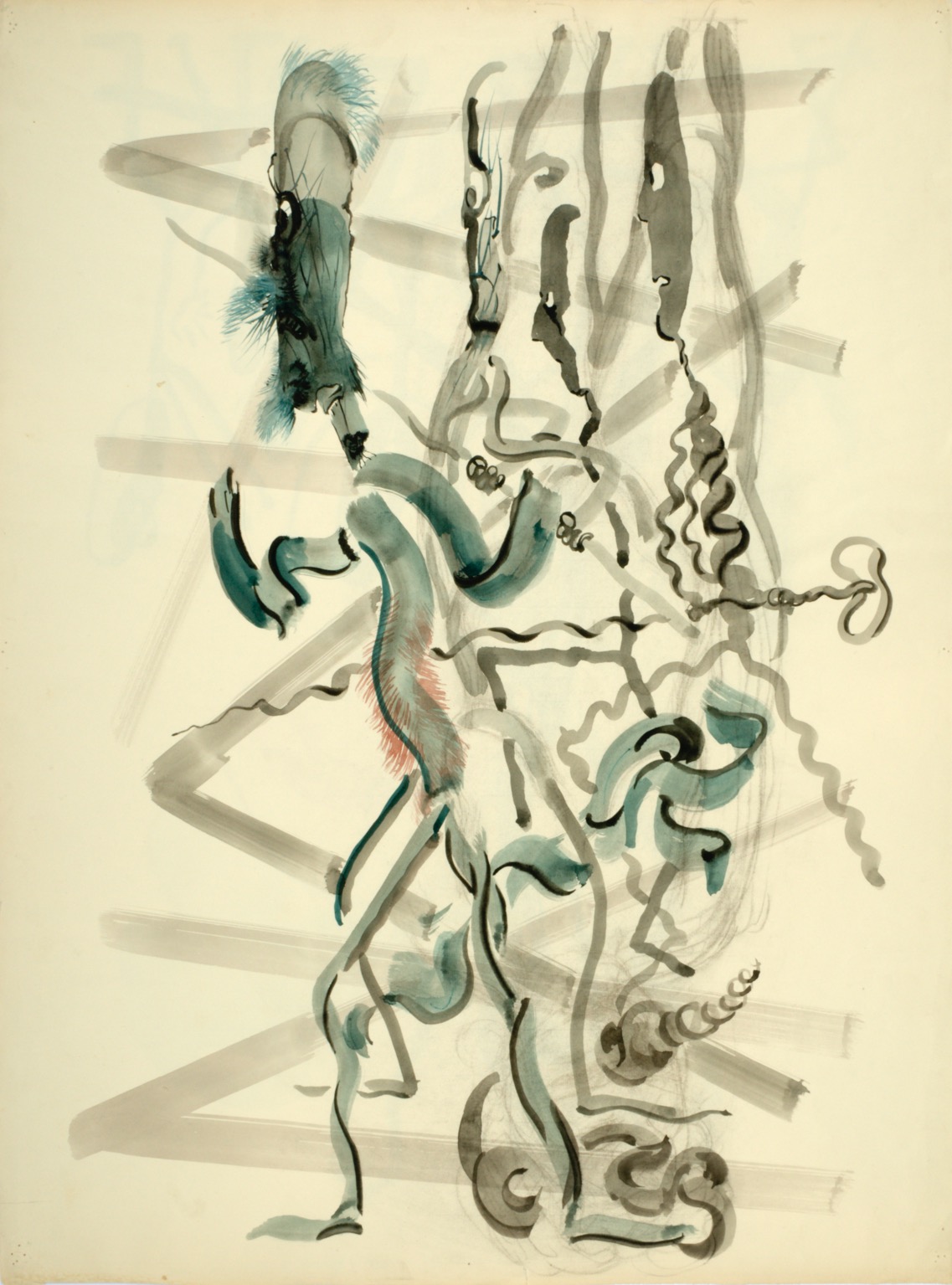

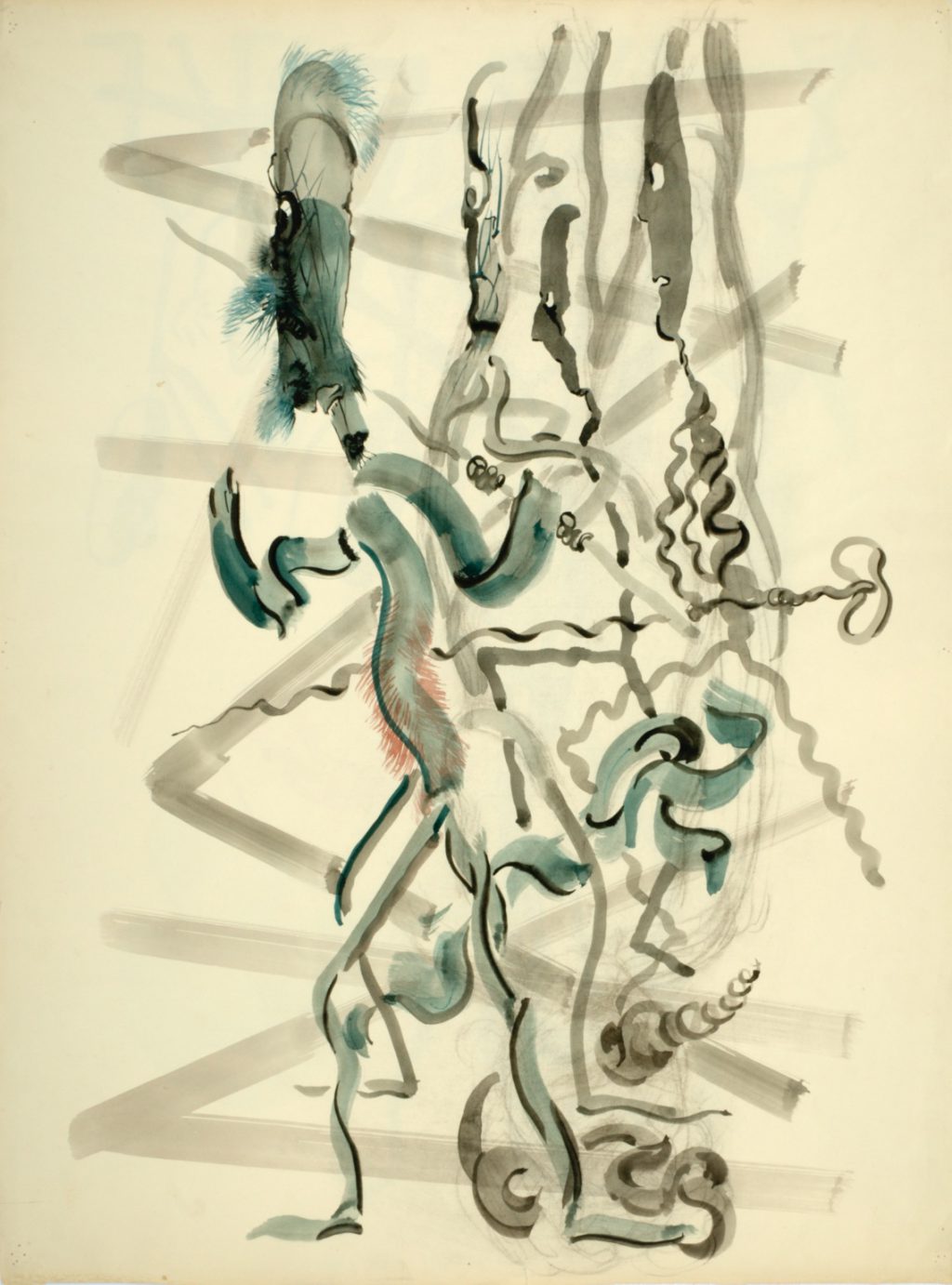

Group of Stickmen

ca. 1949

Watercolor on paper

65.1 × 48.2 cm

Cain or Hitler in Hell

1944

Oil on canvas

99 × 124.5 cm

Sleeping Nude in the Dunes

1940

Watercolour and pen and ink on paper

45.8 × 64.8 cm

Self-Portrait with Nude

1937

Oil on canvas

72 × 58 cm

Myself and the Barroom Mirrror

1937

Oil on canvas

76.7 × 64 cm

So Smells Defeat

1937

Oil on canvas, mounted on cardboard

61 × 50.5 cm

Three Skeleton Key

ca. 1937

Brush, reed pen, pen and ink, and opaque white on paper

59.2 × 46.1 cm

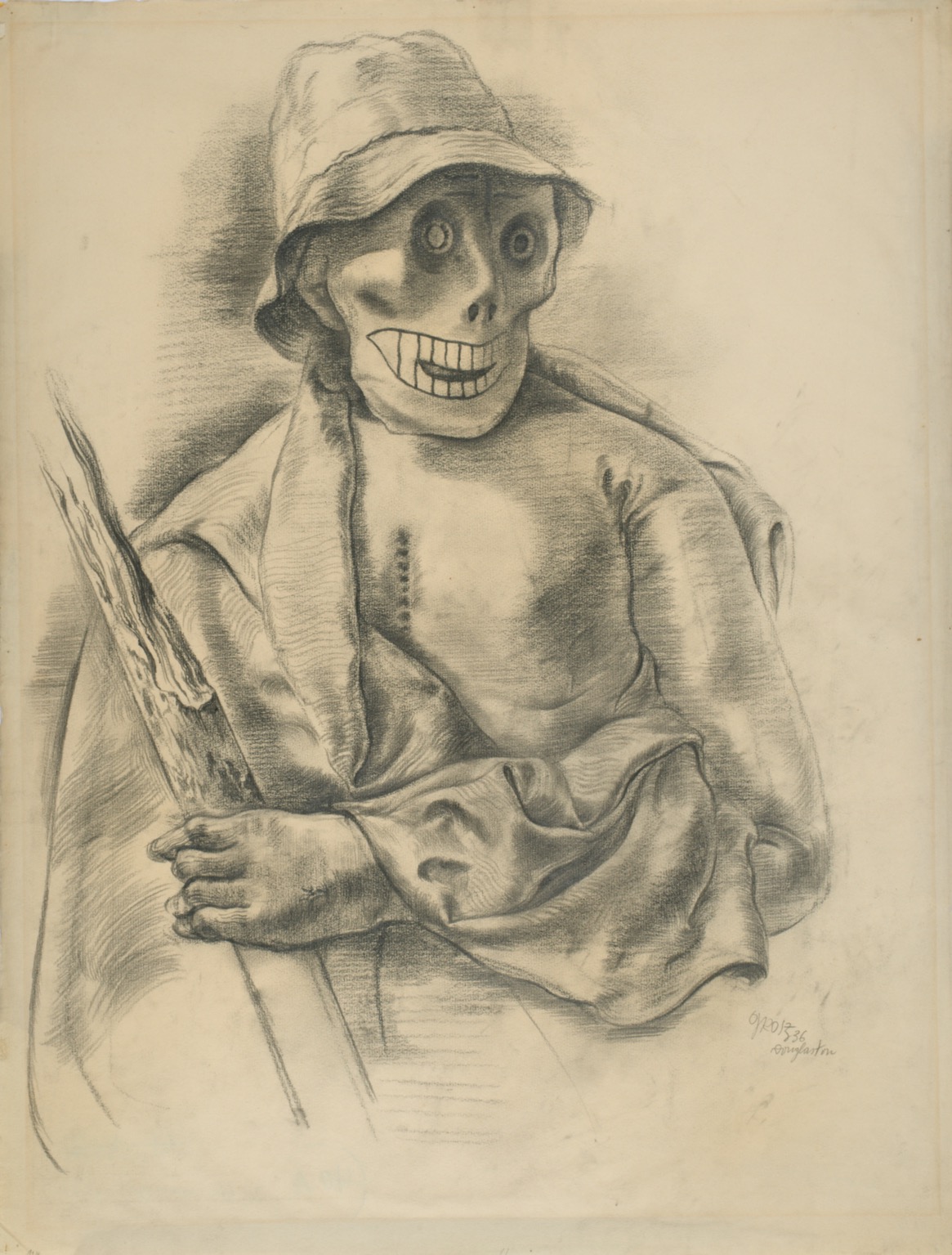

I am always there

1936

charcoal and carpenter’s pencil on paper

63.2 × 48.2 cm

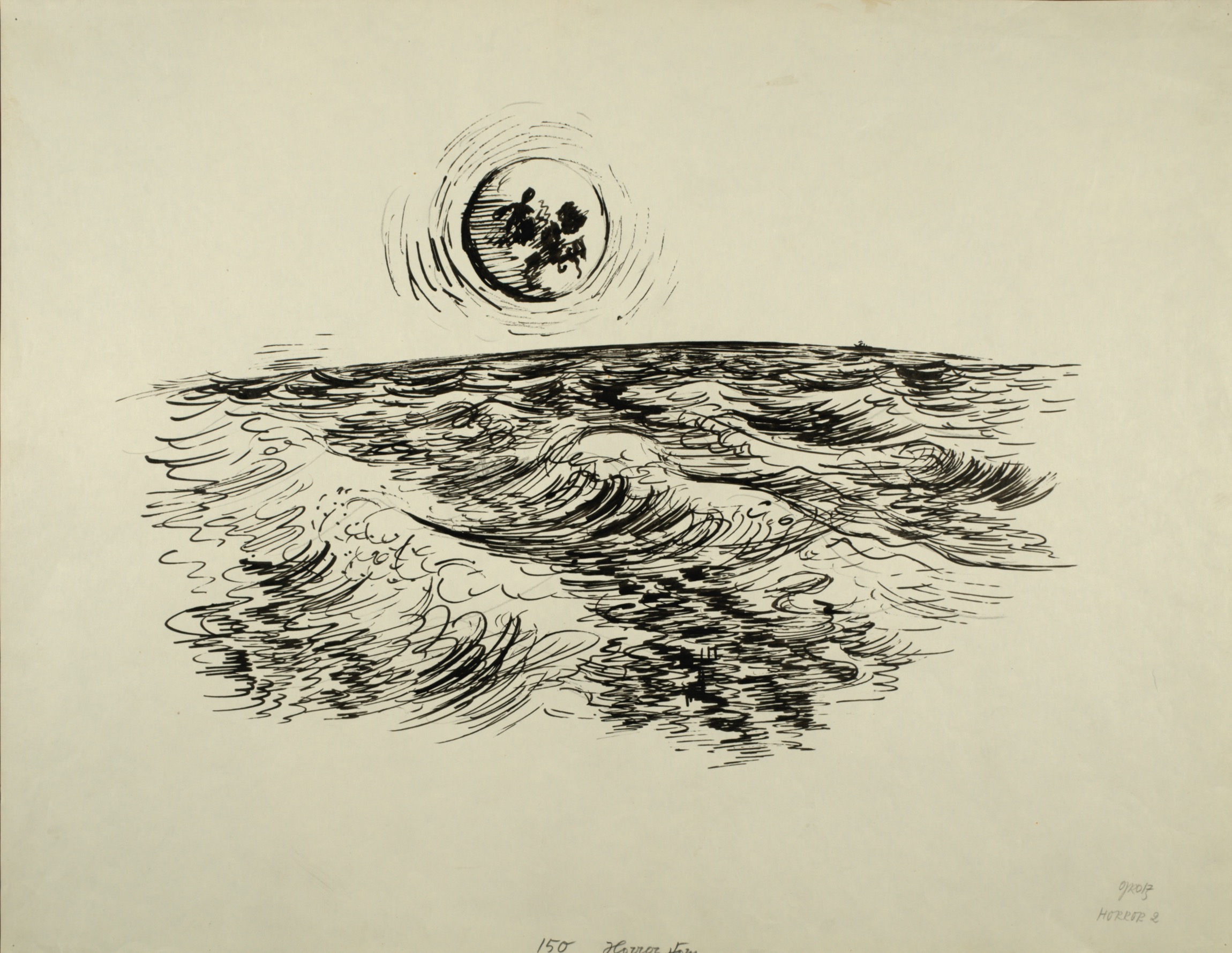

Horror Story

1936

Reed pen over charcoal on paper

46.2 × 59.3 cm

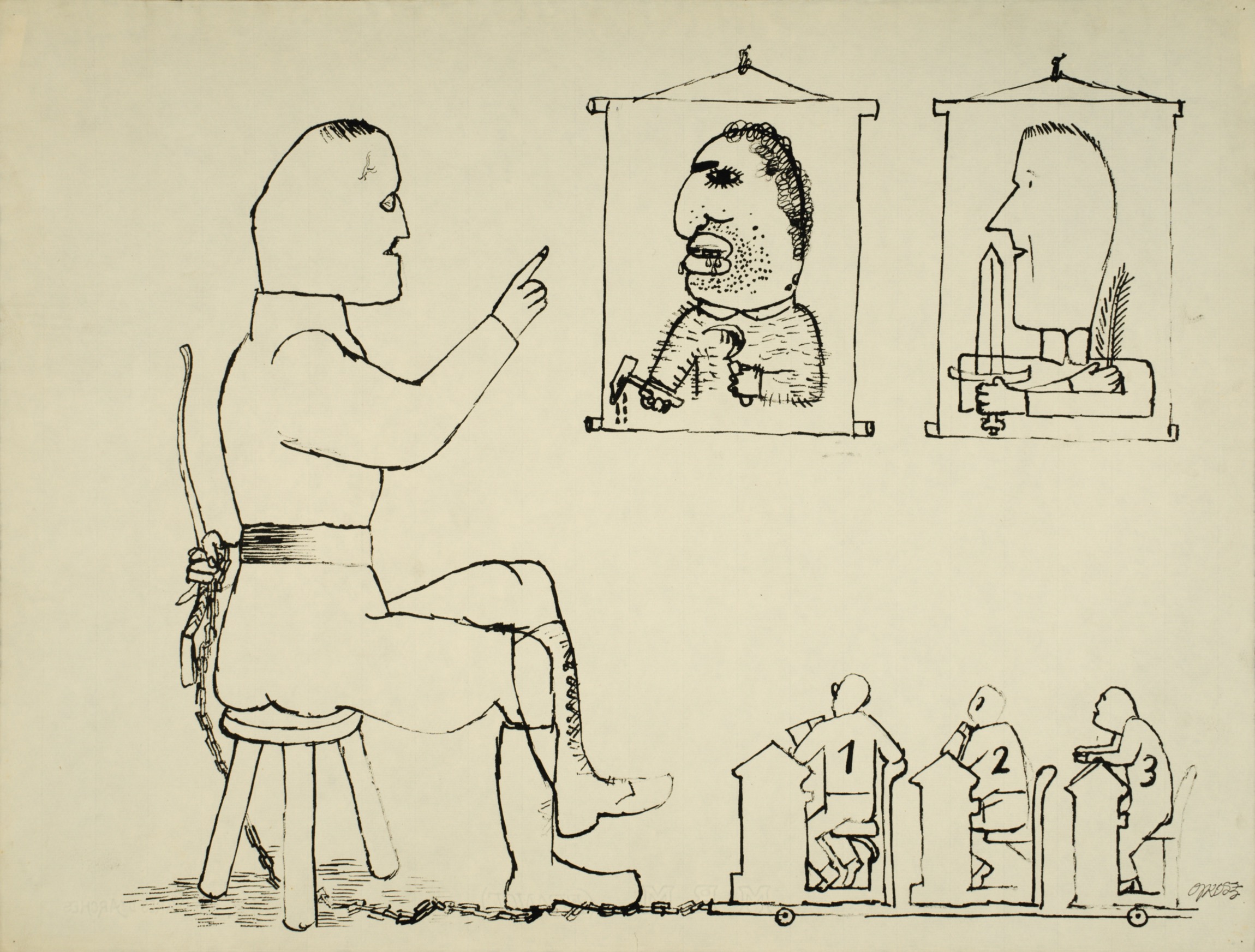

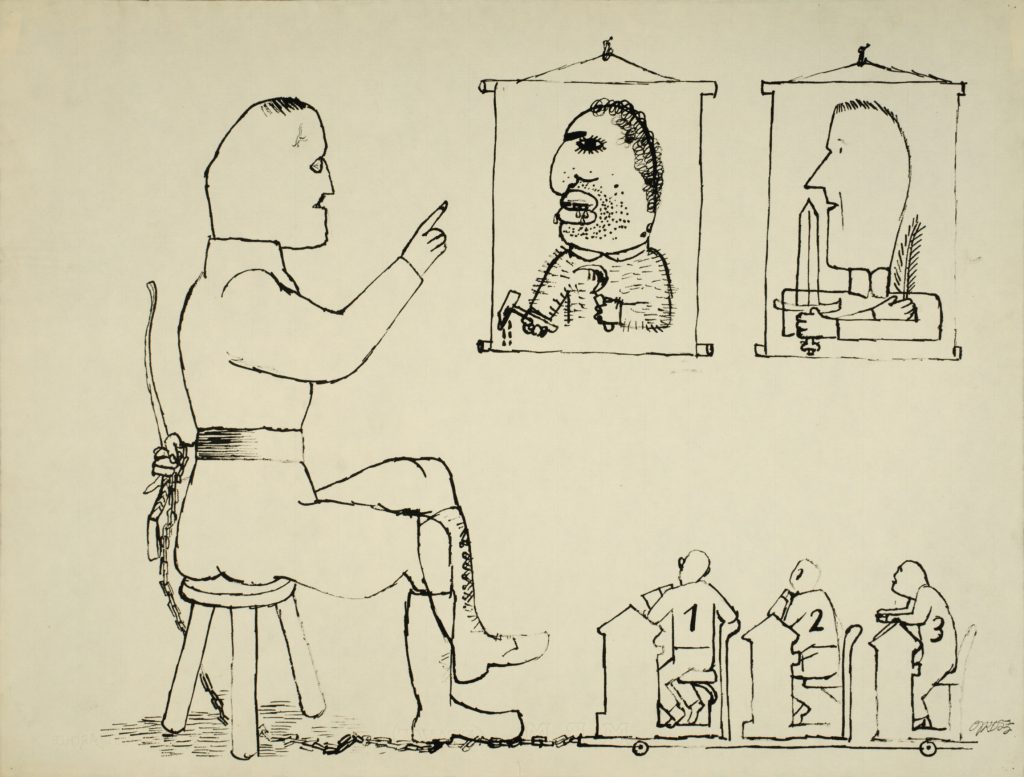

A Lesson for Generations to Come

1936

Reed pen and pen and ink on paper

48.1 × 63.2 cm

Eviction

1935/36

Reed pen on paper

64 × 50 cm

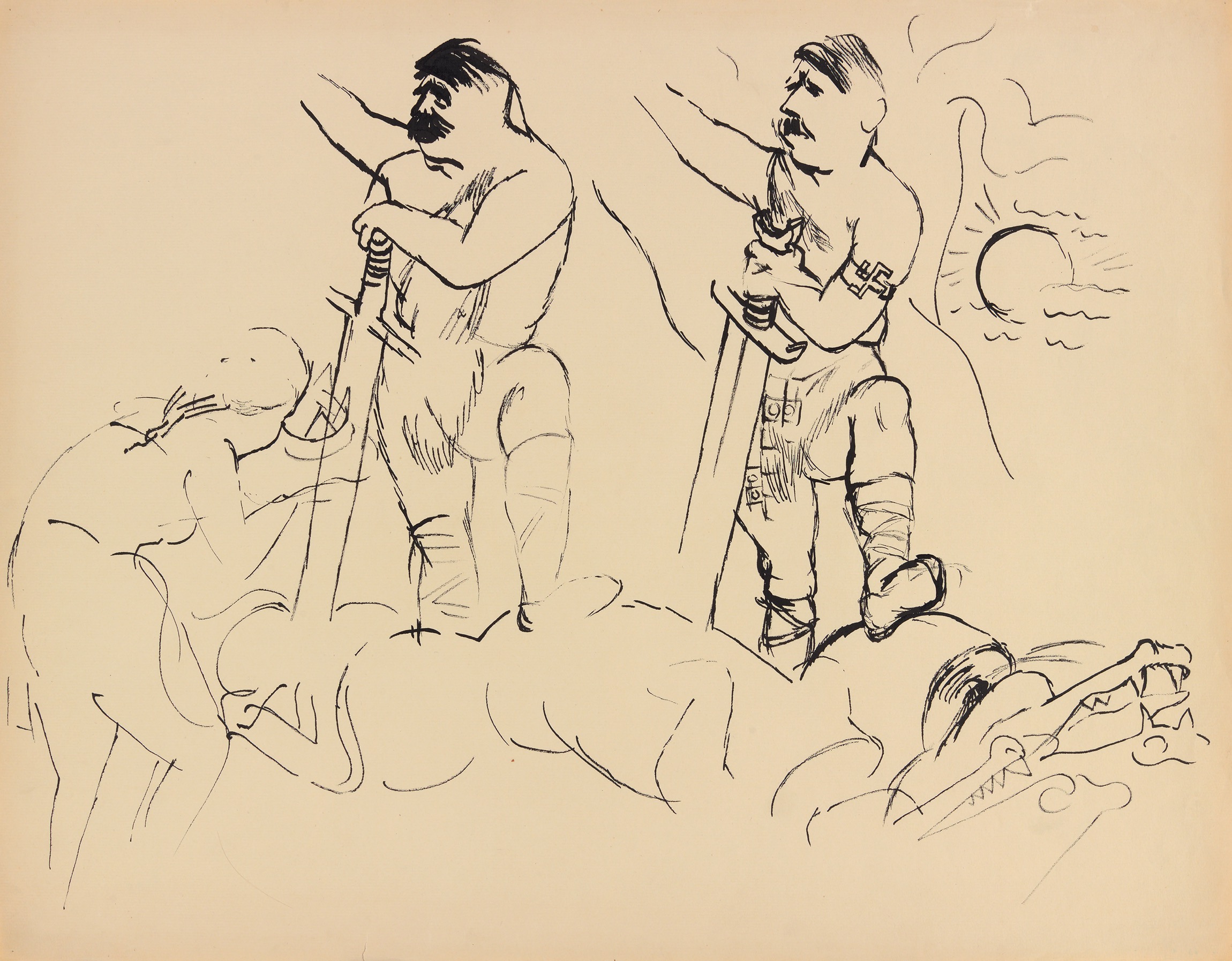

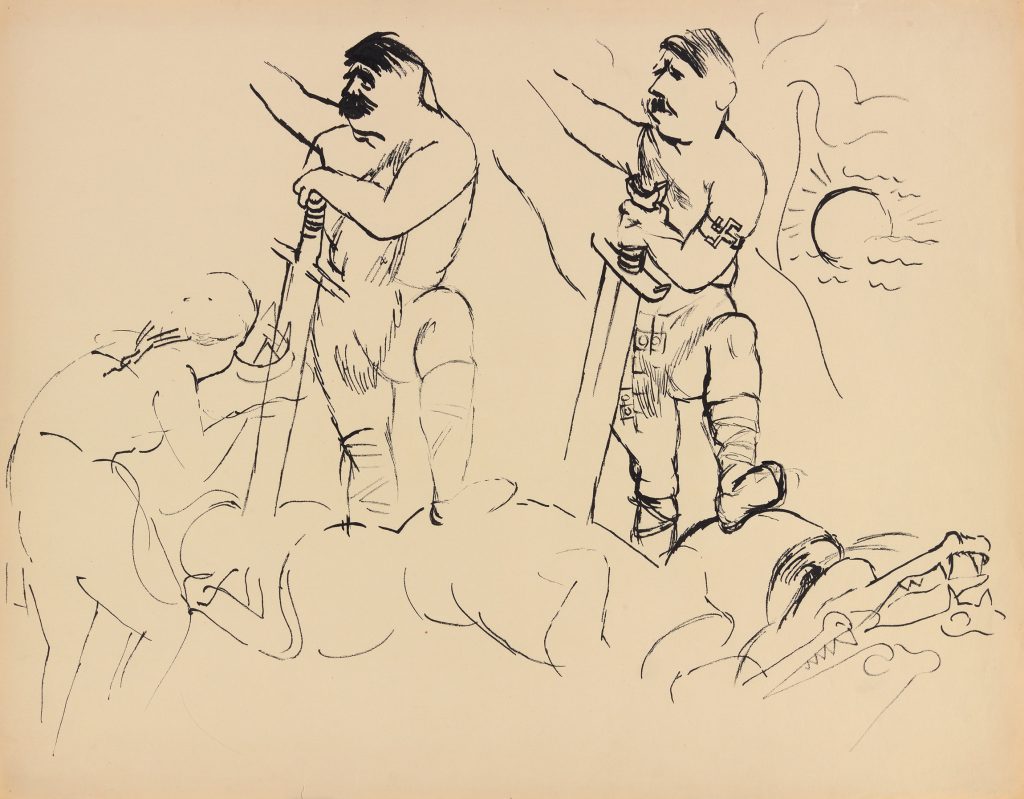

Siegfried Hitler

1935

Reed pen and pen and ink on paper

49.5 × 63.2 cm

Peace

1934

Reed pen, brush, pen and ink, and opaque white over charcoal on paper

47.5 × 62.6 cm

About

Nolan Judin is pleased to present the first major George Grosz exhibition dedicated exclusively to his years in Exile. Over 100 works on view – paintings, watercolors, drawings – and many documents allow for a reassessment of this pivotal figure of 20th Century art.

For 27 years, more than half of his artistically productive life, George Grosz lived and worked in the United States. The fact that it is only now, 50 years after his death, that a first comprehensive exhibition is being dedicated to this important period speaks volumes of the helplessness that has hitherto characterised the art world’s reaction to the complex and contradictory character of Grosz’ work. One widely held opinion states that Grosz lost his much-admired audacity upon emigrating to New York; that he miraculously turned apolitical during the crossing aboard the “Stuttgart” in January 1933, while Nazi henchmen were ransacking his studio in Berlin. Whatever Grosz would paint, draw, or say over the course of following quarter of a century – it was always overshadowed by his socially critical, satirical work of his Weimar Years. Few artists have visually so shaped an era as George Grosz did with the interwar years, through his drawings and his portfolios. For this he was loved and hated, tried in court, and declared a ‘degenerate’ artist.

On first sight, it indeed appears as though after Grosz’ emigration there is little left of his fearlessness, his fiery agitation. By accepting a teaching position at the Art Students League, he executed a radical break with his old life. He had not only escaped from a regime that saw him as an enemy – he also left Germany in bitterness about the country’s workers’ movement and intellectual left, which yielded to the Nazis almost without a fight. His statements (“The air in Manhattan had something inexplicably exciting about it, something that spurred my work onwards… – I was filled with light and colours and joy”) hint at how liberated Grosz felt by having left behind not only Germany, but with that also the obvious defeat of his own artistic mission. Released from the corrosive bitterness of the issues to which he kept returning in Germany, he turned towards the New World full of optimism and amazement. He arrived in New York as a lover: already in 1916 he had played with the idea of emigrating to the US, and had preemptively anglicised his last name, from Groß to Grosz. He also arrived as an admirer of the open society – he could not, nor did he want to, comment on the situation in the America with the same acerbic wit that he had used to chastise Prussian militarism. But it was precisely this witty, extremely critical political artist who was admired by the American public, who was familiar mostly with Grosz’ portfolios.

Continue reading

The first two years saw the production mostly of street scenes and cityscapes that stylistically followed in the vein of the Berlin years. Soon, however, cracks began to appear in the hopeful dreams, pessimism and depression caught up with Grosz. The commercial success he had hoped for never materialised, he increasingly saw his teaching job as a burden, and news from Europe – not only from Germany, also from the Spanish civil war – confirmed his worst fears. When in late 1935 Grosz once again began to paint in oil, he produced extremely gloomy landscapes alongside family portraits and still lifes. More and more he felt a kinship with old masters like Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel, whose premonitions of the Thirty Years’ War inspired him, on the eve of World War II, to depict the apocalypse in a style reminiscent of the old masters.

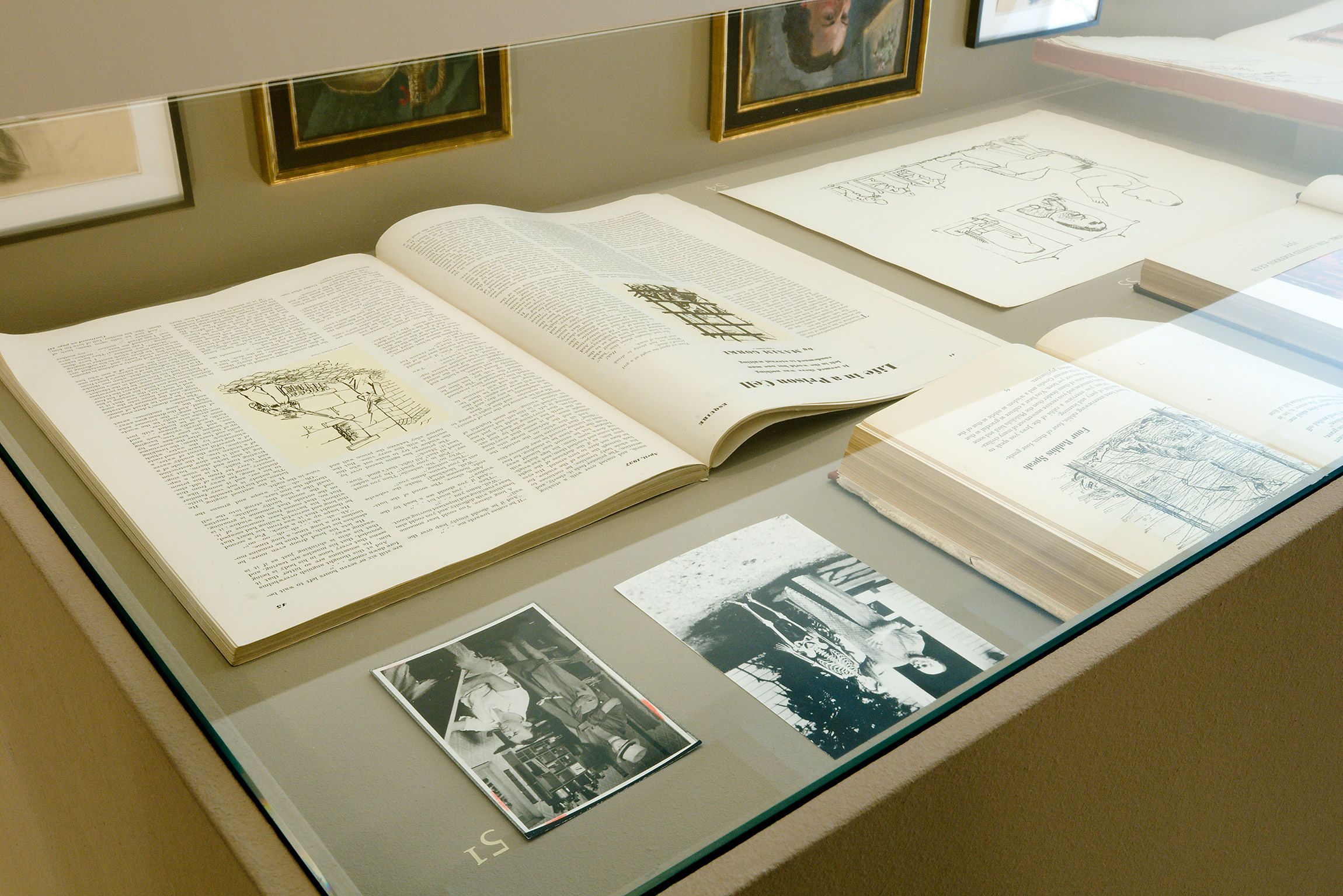

At the same time, Grosz was working as an illustrator for publications such as “Esquire” and “Vanity Fair”, and contributed drawings to short stories by Ben Hecht and O. Henry. But these activities, too, bore with them disappointments: his large, carefully executed works were often reduced to mere stamp-size. “Oddly enough, I was never able to approach the very simplicity and normality of American illustration that I admired so much.” In 1936 he tried to replicate his major successes of the 1920s, “Ecce Homo” and “Der Spießer-Spiegel”, with the portfolio “Interregnum”. Similar success, however, was not forthcoming.

Grosz found moments of happiness with his wife Eva and his sons Peter and Martin on the beaches of Cape Cod. A number of drawings, watercolours and oil paintings of the dune landscape attest to Grosz’ fascination with nature as an artistic topic: the dunes are populated by naked women in more or less explicit poses – and even those landscapes devoid of people remain charged with an obvious eroticism. The quiet landscapes and nudes were cause for criticism and disappointment among old friends and admirers. Grosz confessed to being a “romantic”, and cited Walt Whitman: “I contain multitudes, why should I not contradict myself?” This sentence is key to understanding his artistic personality – particularly of the American years. For here he created not only landscapes and acts, but at the same time highly political works, which Grosz called “images of hell”. In these works, where he gives up on beauty for the sake of a drastic imagery, he conjures up the end of civilisation and sees hell on earth come to pass. He reacted with artistic rage to the torture and murder of his old friend Erich Mühsam by the Nazis and to the stories told by the writer Hans Borchardt after his escape from a concentration camp. The longed-for end of the war brought with it the recognition that humanity was now threatened with a nuclear apocalypse. The “Stickmen”, post-nuclear creatures without bodies, are Grosz’ last major group of works, culminating in the haunting “Painter of the Hole”. He bade farewell to America with a group of collages – a joyful return to a technique of the Berlin years: “You stay dada all your life.” Grosz died in July 1959, only a few months after returning to Berlin.

“When he finally returned from New York to Berlin in 1959 he remarked in surprise how American the city had become. With this comment, Grosz had returned home in a number of ways. George Grosz, his art and his biography exemplify the life of artists and intellectuals in the 20th century, as well as Germany’s glory and misery in this century. In this sense, too, Grosz is an epochal figure.”

— Peter-Klaus Schuster

Catalogue

The Years in America

1933–1958

Edited by Juerg Judin

Texts by Barbara McCloskey, Ralph Jentsch and Juerg Judin

Two editions: German or English

250 × 315 mm

280 pages, hardcover

151 color ill., 52 b&w ill.

Published by Hatje Catz, Ostfildern 2009

ISBN 978-3-7757-2434-0