Uwe Wittwer

Andere Orte — Wäldchen

Works

Interior after De Hooch

2011

Oil on canvas

80 × 60 cm

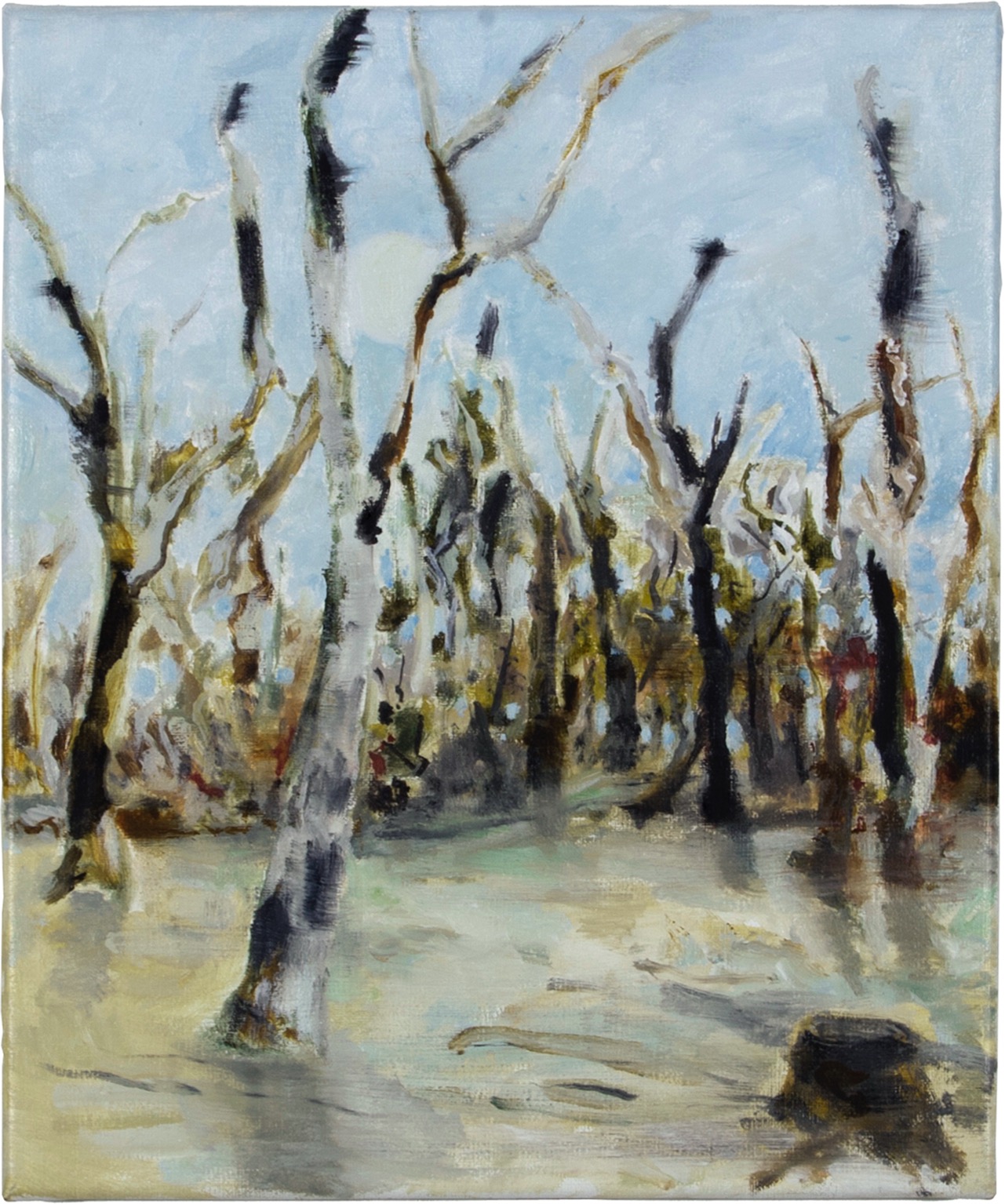

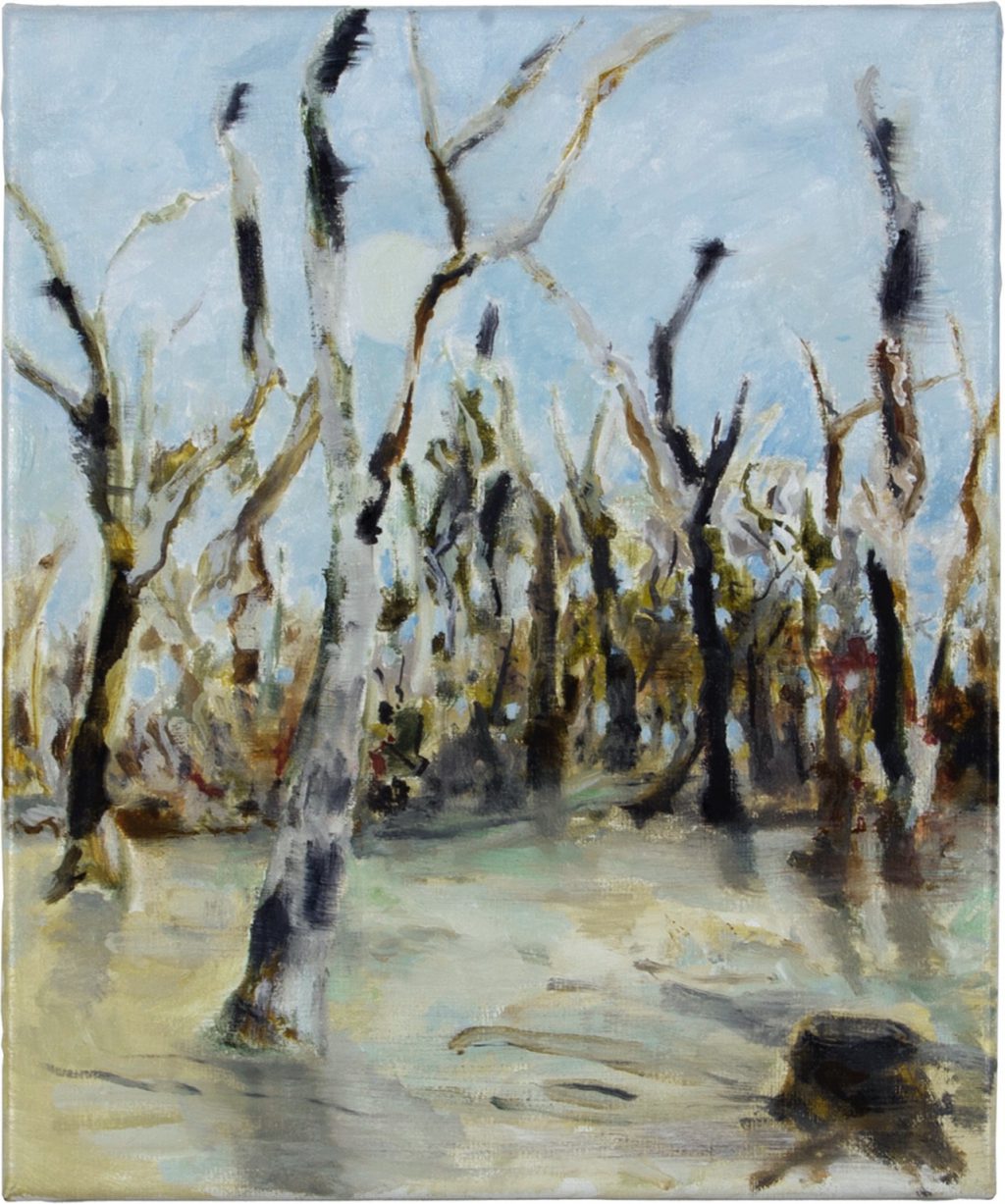

Copse

2011

Oil on canvas

30 × 25 cm

Still Life Negative after van der Ast

2010

Oil on canvas

60 × 70 cm

Still Life

2011

Oil on canvas

145 × 160 cm

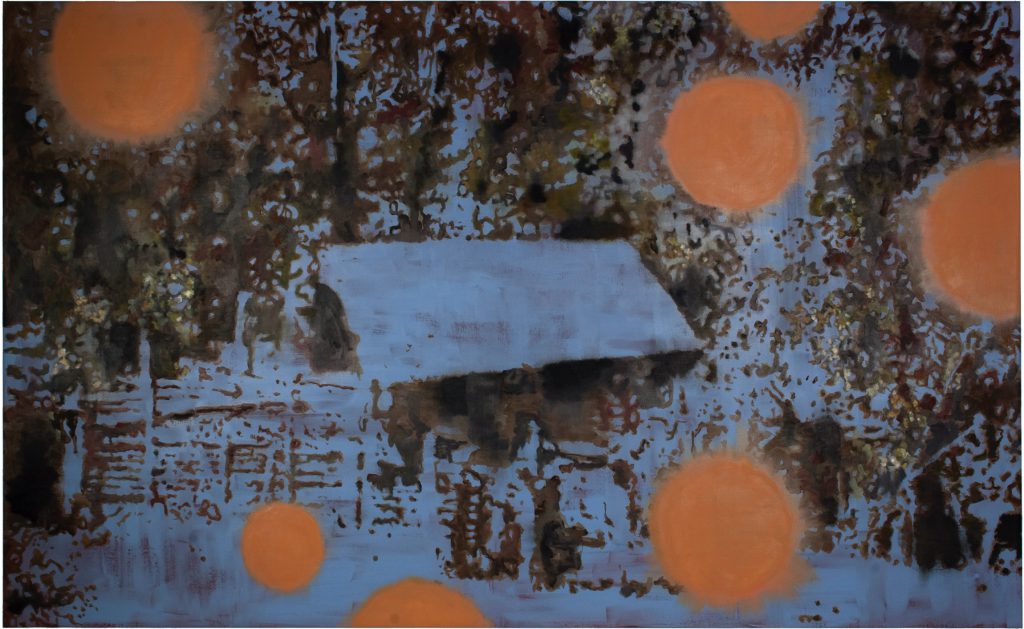

House, Camp

2010

Oil on canvas

160 × 260 cm

Interior, Camp

2010

Oil on canvas

110 × 100 cm

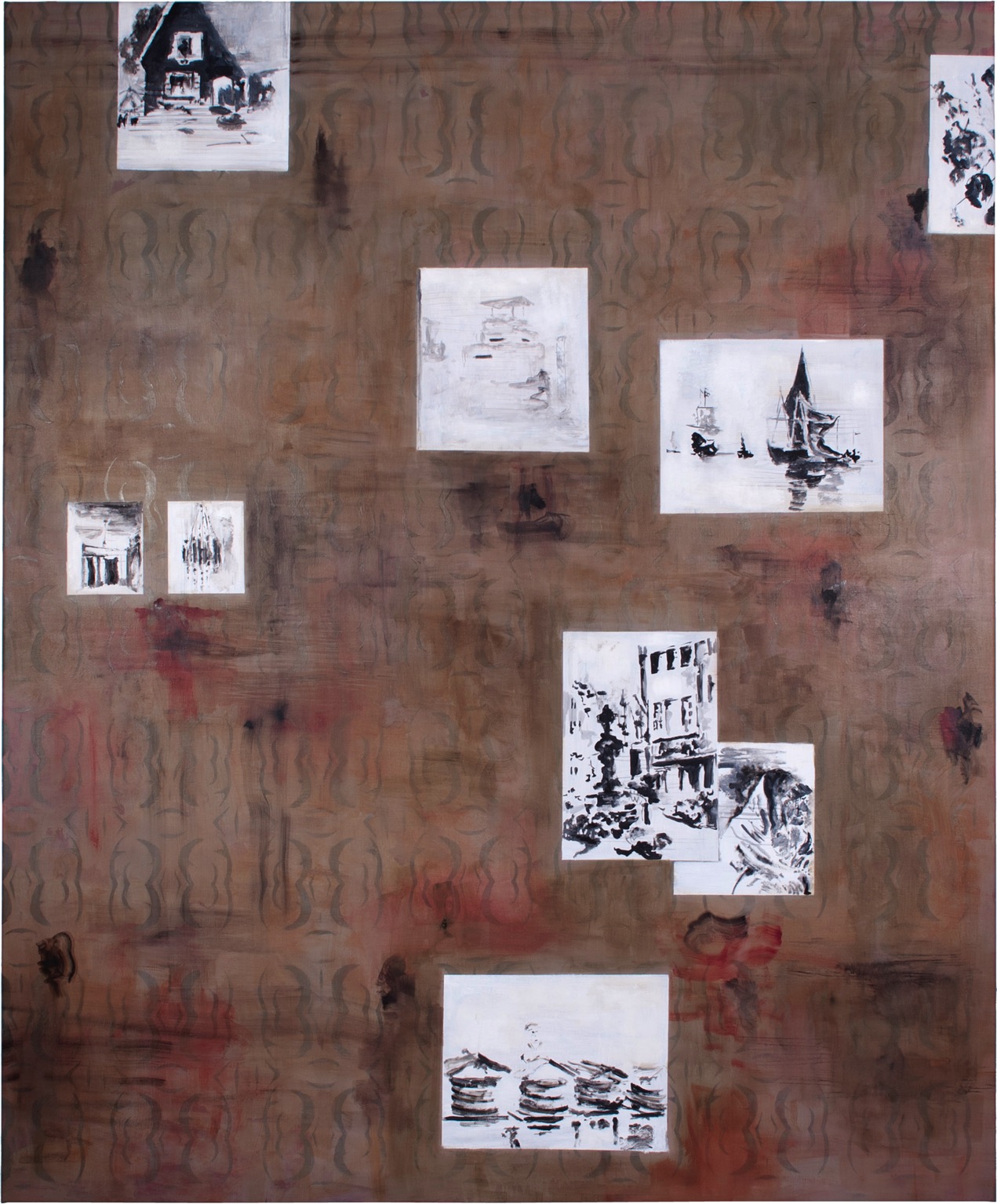

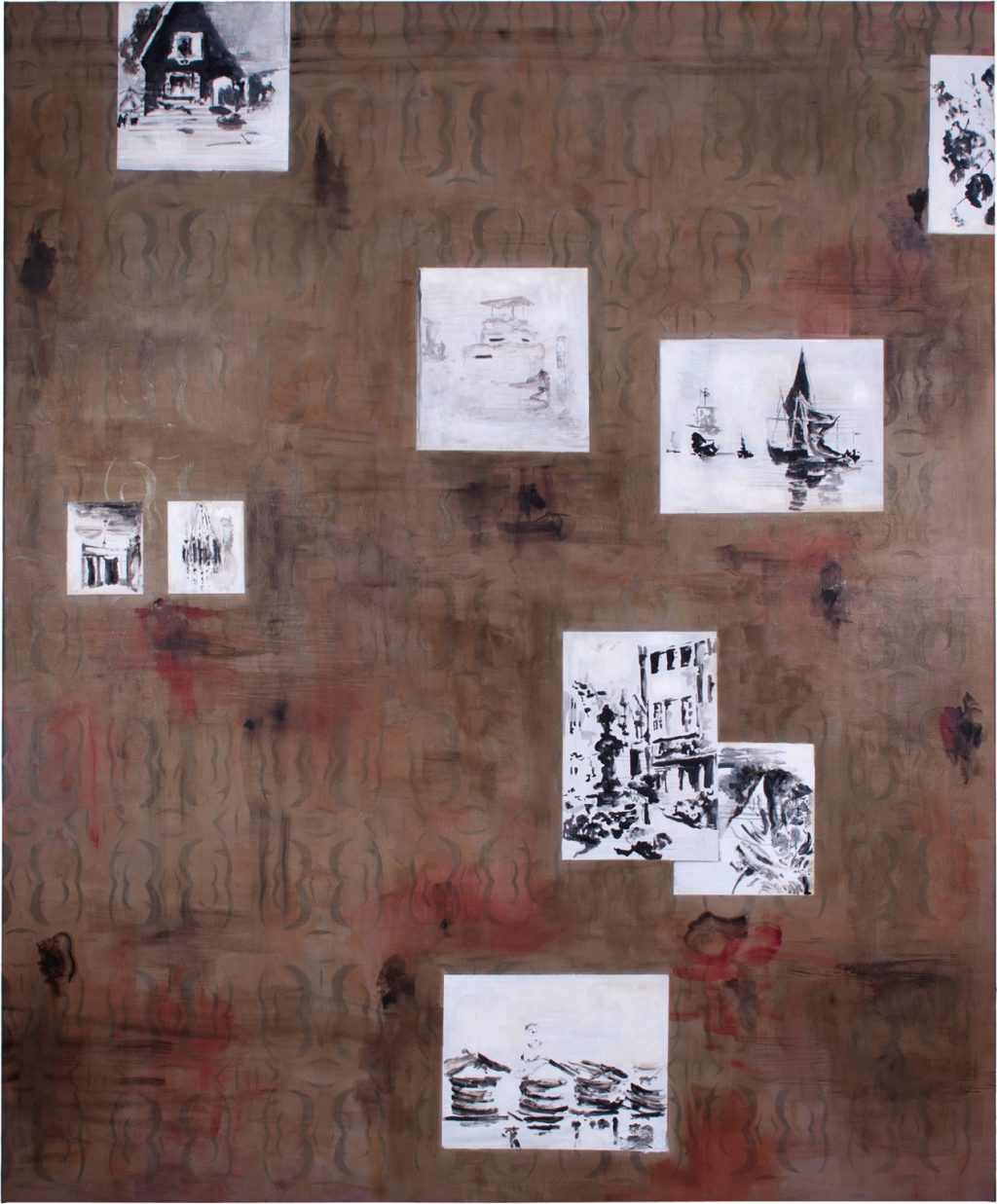

Wall Piece

2011

Oil on canvas

180 × 150 cm

Evening

2010

Oil on canvas

100 × 110 cm

Fool

2011

Oil on canvas

180 × 150 cm

Caravan Negative

2010

Oil on canvas

140 × 200 cm

The Dance Negative after Watteau

2010

Oil on canvas

110 × 130 cm

Three Sisters

2010

Oil on canvas

140 × 200 cm

Rotor

2010

Oil on canvas

110 × 130 cm

Interior

2011

Oil on canvas

70 × 60 cm

Winter Landscape

2011

Oil on canvas

160 × 220 cm

Text

Two central themes in Swiss artist Uwe Wittwer’s extensive oeuvre are the “truth of the image” and “image recollection”. In an age dominated by (digital) media, where the line between real and fake – or ‘edited’ – is increasingly blurred, the question of the relationship between image, effect and reality becomes ever more important. And indeed, the point of departure of Wittwer’s works are digital images found on the internet, whose authors always remain anonymous. With the help of image processing software he manipulates his source material until such a point where the images become his own and he can transfer them onto canvas or paper. Allusions and omissions, fuzziness and inversions into the negative produce works that play with our viewing habits and image recollection in highly suggestive ways. It is part of the dialectic of Wittwer’s works that their apparent sensuality and beauty are only surface-phenomena – beneath it, we often encounter menace and terror.

After “Verwehung” (Drift), the almost epic presentation of works on paper, Uwe Wittwer’s second solo exhibition in this space, with its mysterious title “Andere Orte – Wäldchen” (Other Places – Grove) consists of paintings only. In addition to this formal difference, the artist has also shifted his thematic focus. For years he has focused on the simultaneous development of a small number of series. Wittwer’s oeuvre is like the pattern of overlapping, concentric circles that results from throwing a handful of stones into water. For Verwehung, Wittwer threw – to stick with the image – a large single stone into the water, given that it opened a new series that could be described as “Eastern Prussian Idyll and Expulsion”. The titular principal work of this show was a cycle of 77 nearly monochromatic watercolours whose motives were based on pre World War II photographs found on the internet. This treasure trove of images is of similar importance to the further development of this series as the famous “Atlas” was for Gerhard Richter’s paintings.

Continue reading

It is thus not surprising that the visitor of this show once again encounters motives from Verwehung – this time on canvas, and alongside motives from earlier series. Wittwer’s impressive discipline in sticking to topics increases the viewer’s joy of recognition. He began using and manipulating Old Masters and anonymous family snapshots as far back as the early 90s, and ‘groves’, ‘houses’ and ‘interiors’ already appeared in his paintings back then. Those who have followed his work over the last 20 years will experience a déjà-vu that does not bore but fascinate as it uncovers ever new layers of meaning in the same motive.

The “Wäldchen” (Grove), that has given the exhibition its title graces the smallest canvas – and is by no means the natural idyll one might expect. Naked trunks and branches in the foreground as well as an ominous red in the background point to the fact that this is a forest on fire. It is no place of repose, not even the viewer’s gaze finds a point of rest. It is a utopos, a non-place so typical of Wittwer’s repertoire, seemingly familiar but nonetheless ambivalent and threatening. It is also one of the few images that is not based on a photograph found online.

At second glance we can also spot a fire in the dark image “Im Garten” (In the Garden). The two children in the foreground, reminiscent of Hänsel and Gretel, might be grinning at the viewer, but will soon take off as the house in the background is engulfed by flames.

The “Drei Schwestern” (Three Sisters), too, are staring frontally at the observer. We already encountered them in Verwehung and it is still unclear whether they are wearing their buttoned-up coats to Sunday mass – or whether they are getting ready to flee their wintery home.

The almost monumental “Winterlandschaft” (Winter Landscape), however, definitely deals with the theme of flight. Horses pull a fully laden hay carriage through a snowy landscape. The painting’s colour scheme is extremely reduced, but very cleverly construed: the primary colour blue turns up in both cool and warm tones, and is further enhanced by a complementary note of peach in the trees in the background. While Wittwer renders clearly the motive of the carriage in flight, we find a deep ambivalence in the time of day. The pale circle in the sky could both be the sun and a full moon. The scene’s stage-like quality is further amplified by its careful composition (with the bit of ruin on the left counterposed to the tree on the right).

The image “Narr” (Fool), remains mysterious even to those who know the drawing on which it is based, “Laute spielender Narr, ein Bein über den Nacken legend” (Fool Playing the Lute, One Leg Slung Over His Neck), 1605, by Anton Möller the Elder. The bizarre anatomy might be explained with a wooden leg that seems to protrude from the fool’s torso, with a small dog jumping at it. On this reading, the ‘leg’ slung over the neck would merely be a trouser leg, useless to the one-legged fool. The scene is by no means amusing, the presence of a fool notwithstanding. At best, he reminds us of the figure of the juggler at a country fair – more likely, though, we are looking at a casualty of war. Both the original drawing and Wittwer’s painting surprise with their pitiless gaze.

In “Interieur” (Interior), strange blotches of colour seem to float in the hallway of an uninhabited house. They do not have a function in the interior and escape a figurative approach. Wittwer here plays with the fact that, upon viewing an image that is representational rather than abstract, our consciousness of the process by which it was painted immediately recedes into the background. As he puts it, “I simply put pigments onto canvas in a particular order”. With the floating blotches, in which our gaze, schooled as it is by science-fiction, immediately recognises a frightening apparition, the artist is merely pointing us to the colour as such. In a related painting, “Haus” (House), we see a standard issue little house with walled-up windows. It might stand somewhere close to the grove in “Wäldchen”, and its inside might be full of floating blotches of colour. Wittwer refers to it as the “painter’s house”, hinting at the hermetic qualities of the artistic process: the painter as alchemist looks inward, not outward.

Just like the “Haus”, the chromatically fascinating image “Caravan negativ”, too, is a non-place – or indeed the “Anderer Ort” (Other Place) in the exhibition’s title. This is also true for the ferris wheel’s silhouette in “Abend” (Evening). In the background of the supposed fair a viaduct reaches towards the evening sky, which evoke Caspar David Friedrich’s depictions of ruins.

In “Der Tanz negativ nach Watteau” (The Dance Negative After Watteau), Wittwer seems to have found an idyll that is disturbed by neither fire nor flight: In Watteau’s 1720 original, a coquettish girl is about to do a little dance for her three young companions. One of them plays the flute, while the girl smiles at the observer. Even Frederick the Great fell for the charms of this image, which he acquired for his Potsdam residence in 1766. Within a work of art’s history of reception, we may choose to ignore its provenance. It is thus only for the initiated that the idyll of this little dance is darkened by the fact that Hitler acquired this painting for his personal collection in 1942. Today it hangs in the Berliner Gemäldegalerie, where Wittwer came across it on one of his regular visits. He knew nothing of the dark blotches that mar its past.

The exhibition “Andere Orte – Wäldchen” comprises 25 paintings that were created in 2010 and 2011.