Uwe Wittwer

Der Brief

Works

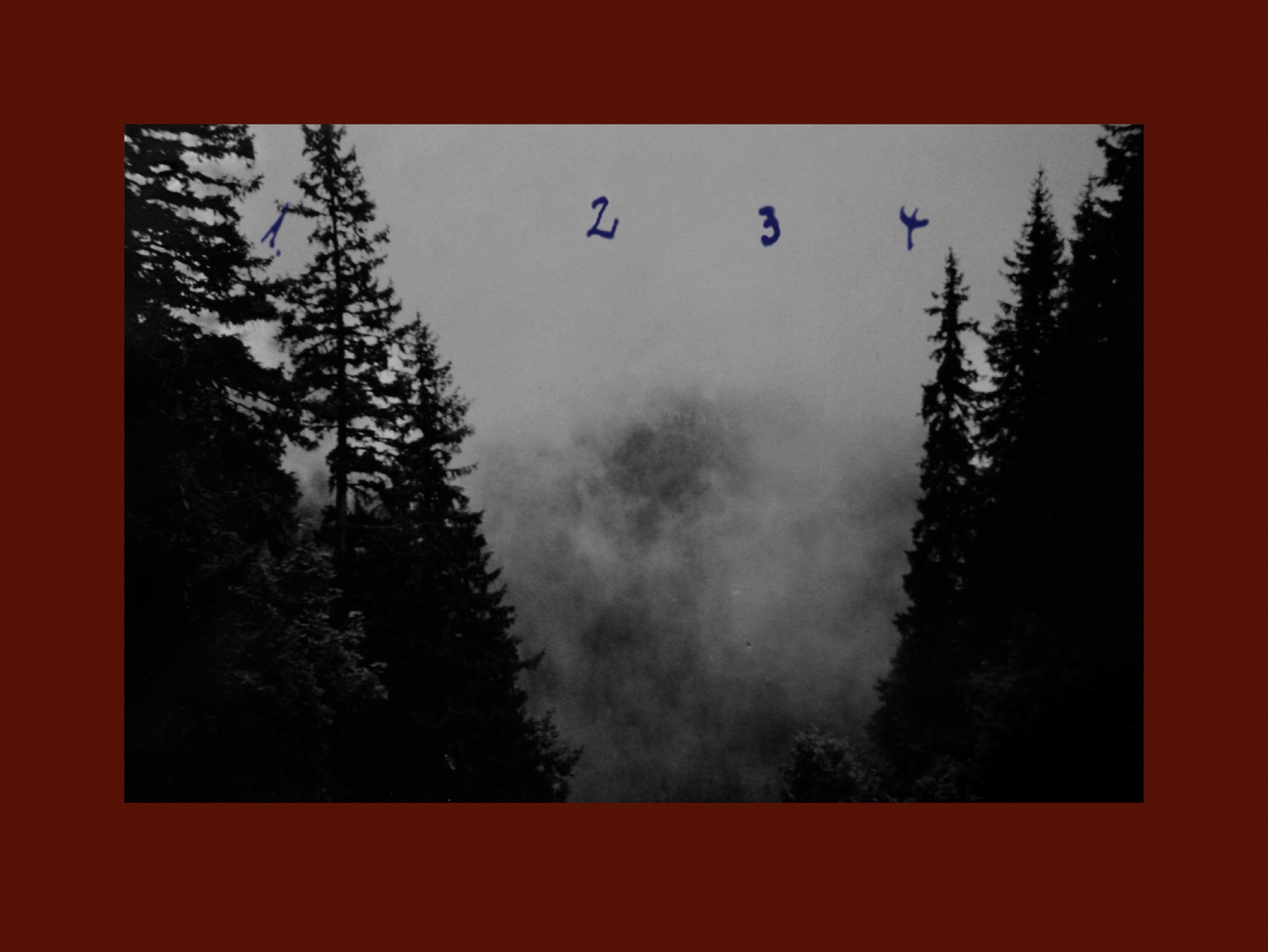

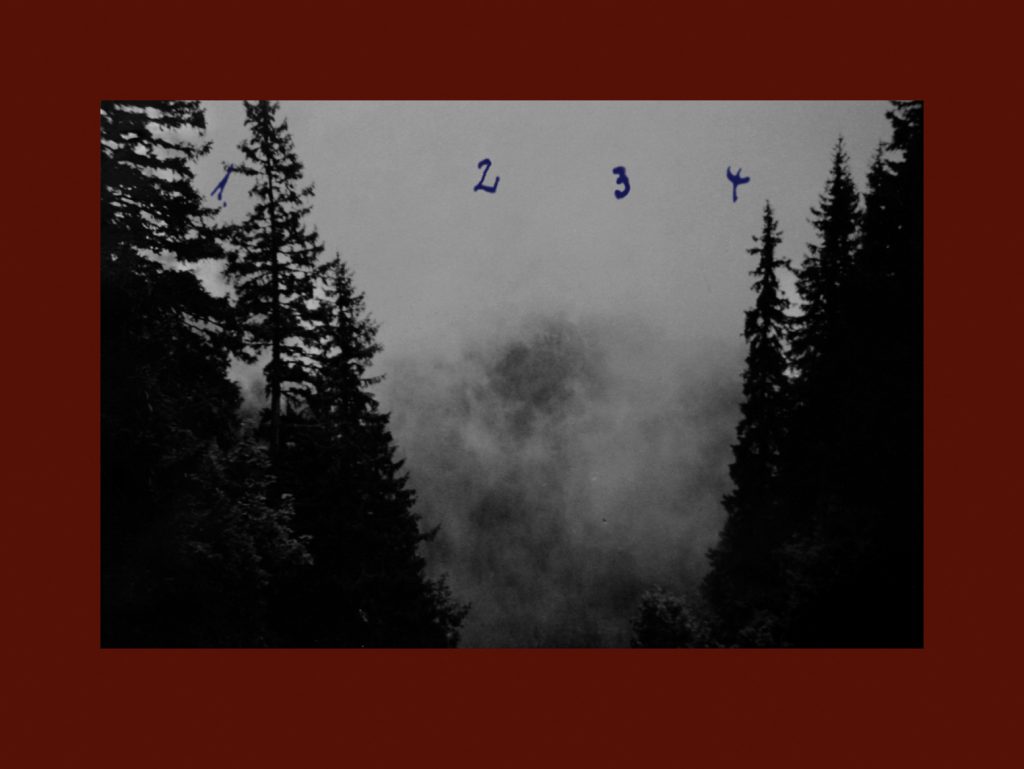

Waldstück

2013

Inkjet on paper

112 × 150 cm

Waldstück negativ

2013

Inkjet on paper

140 × 206 cm

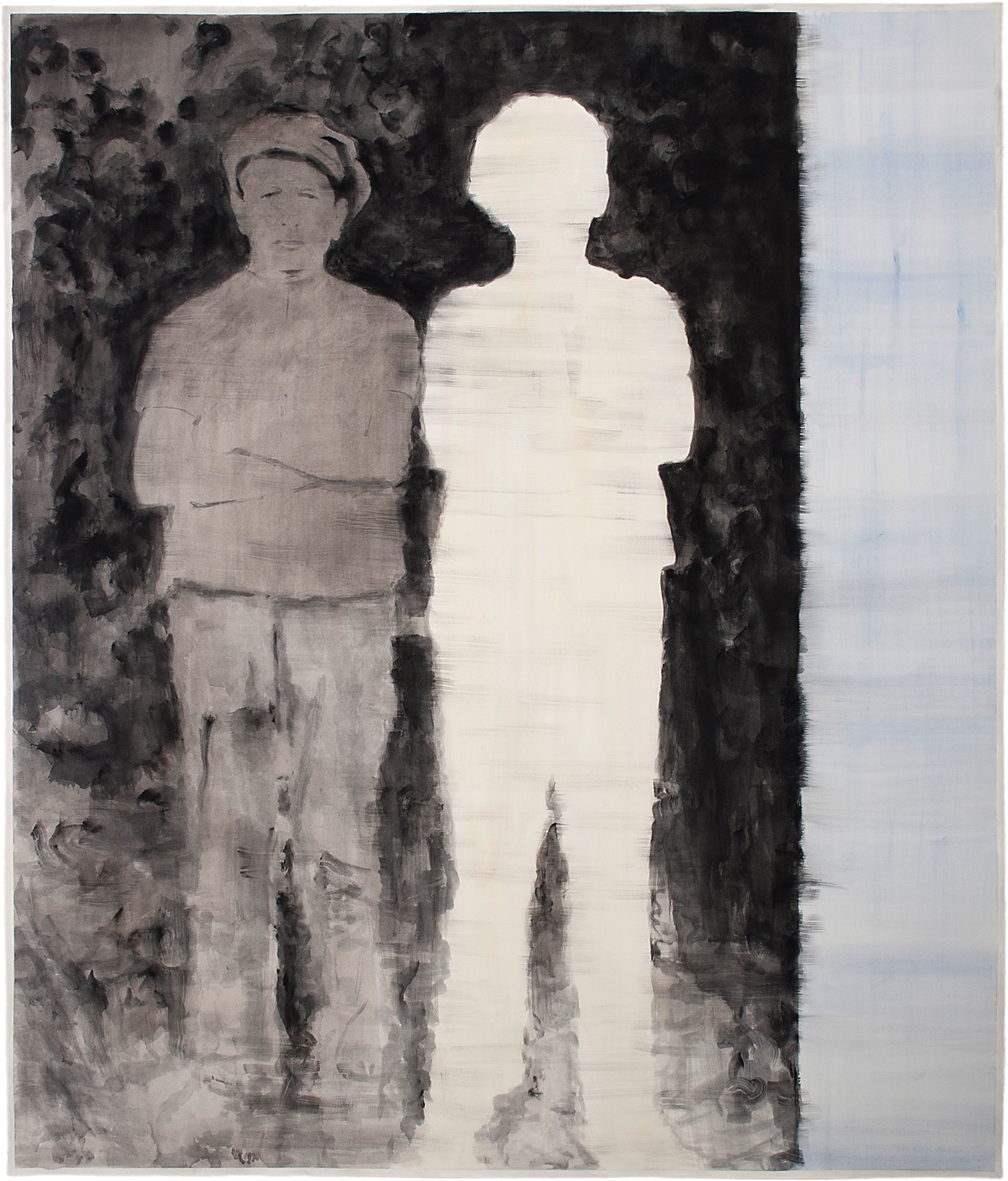

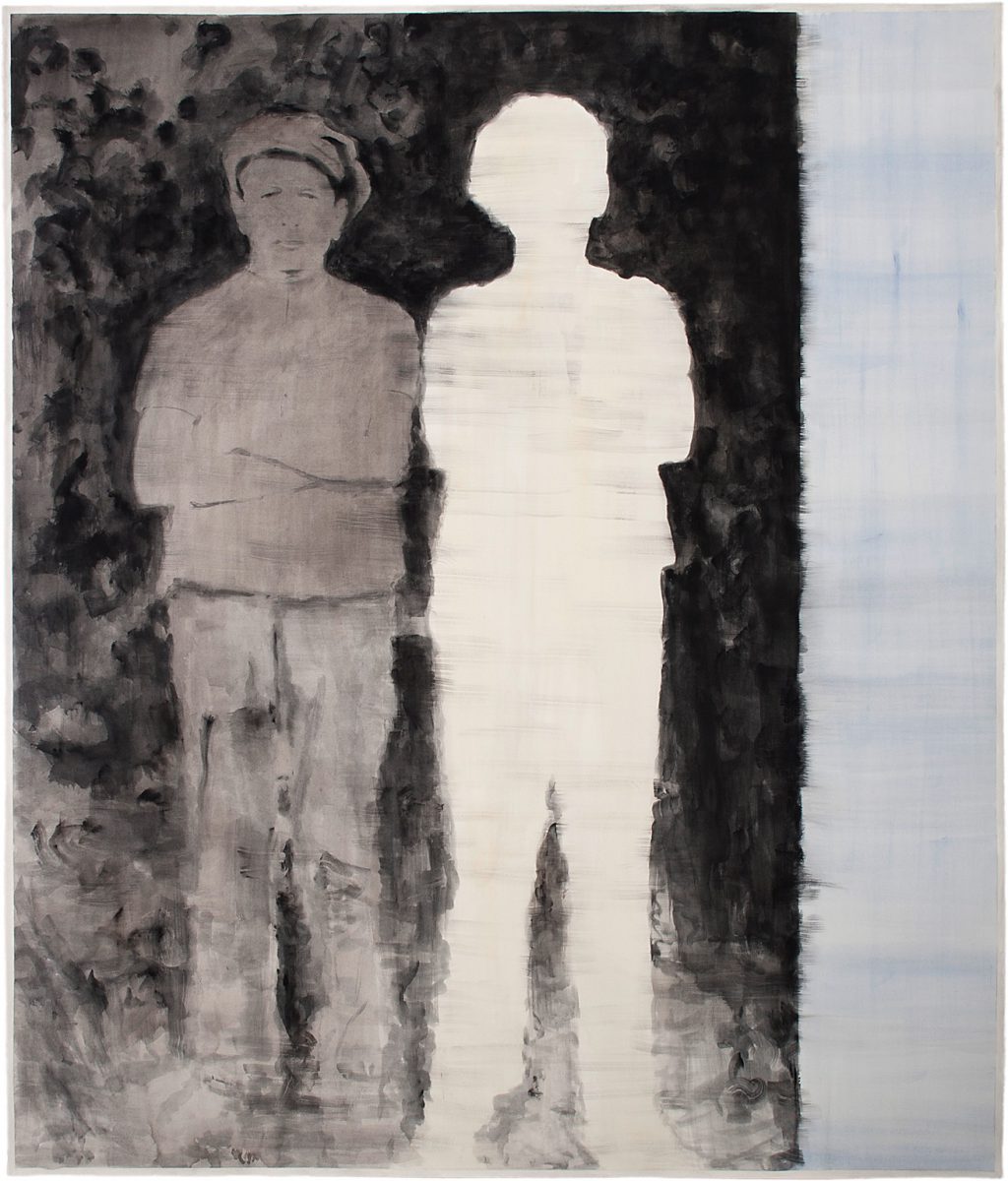

Doppelportrait (Double Portrait)

2013

Watercolour on paper

180 × 154 cm

Landschaft (Landscape)

2013

Watercolour on paper

70 × 90 cm

Stillleben negativ (Still Life negative)

2013

Watercolour on paper

70 × 90 cm

Reiter (Rider)

2013

Watercolour on paper

260 × 180 cm

Bienenhäuser (Bee Houses)

2013

Watercolour on paper

90 × 130 cm

Reiter negativ (Rider negative)

2013

Watercolour on paper

114 × 114 cm

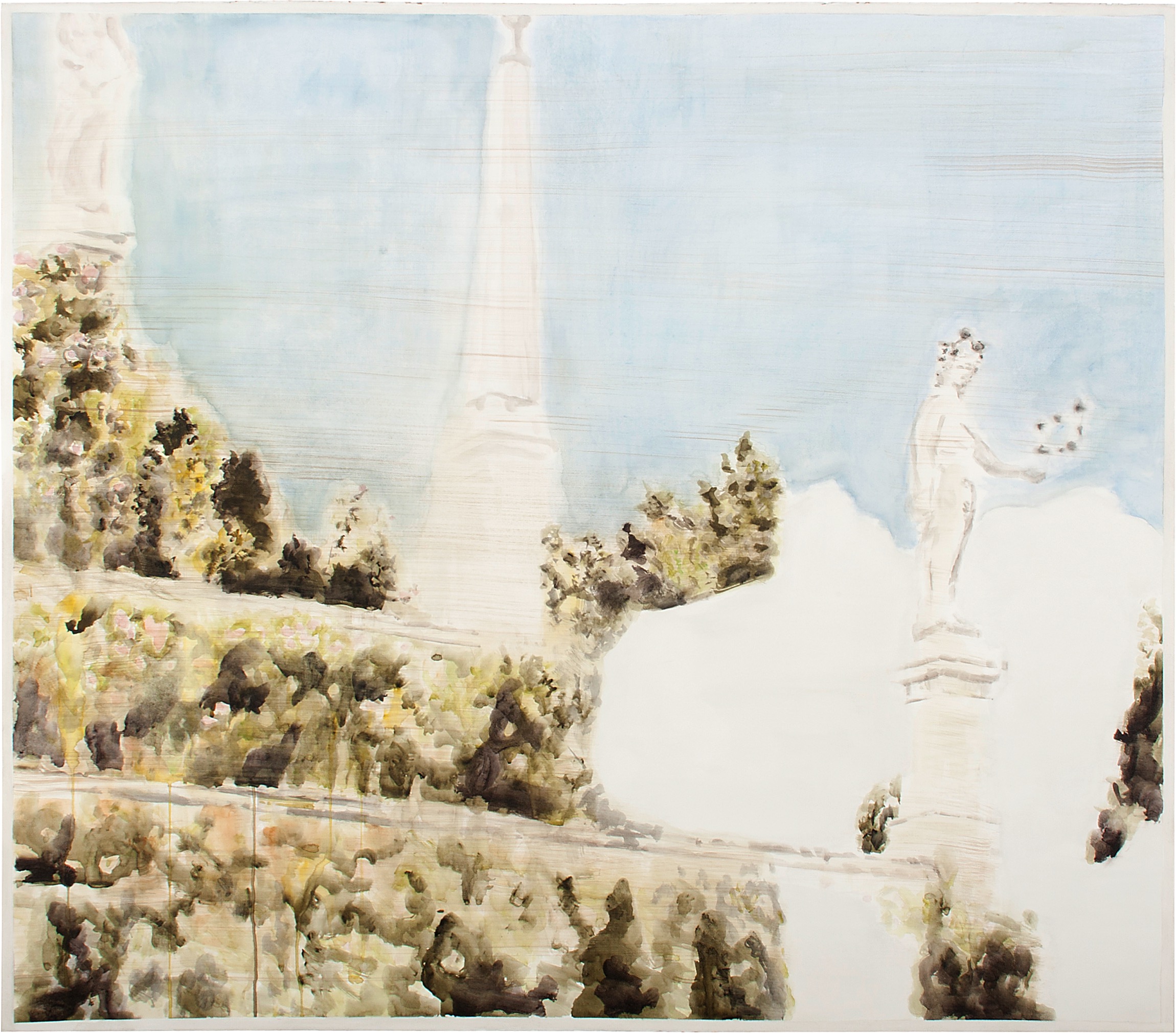

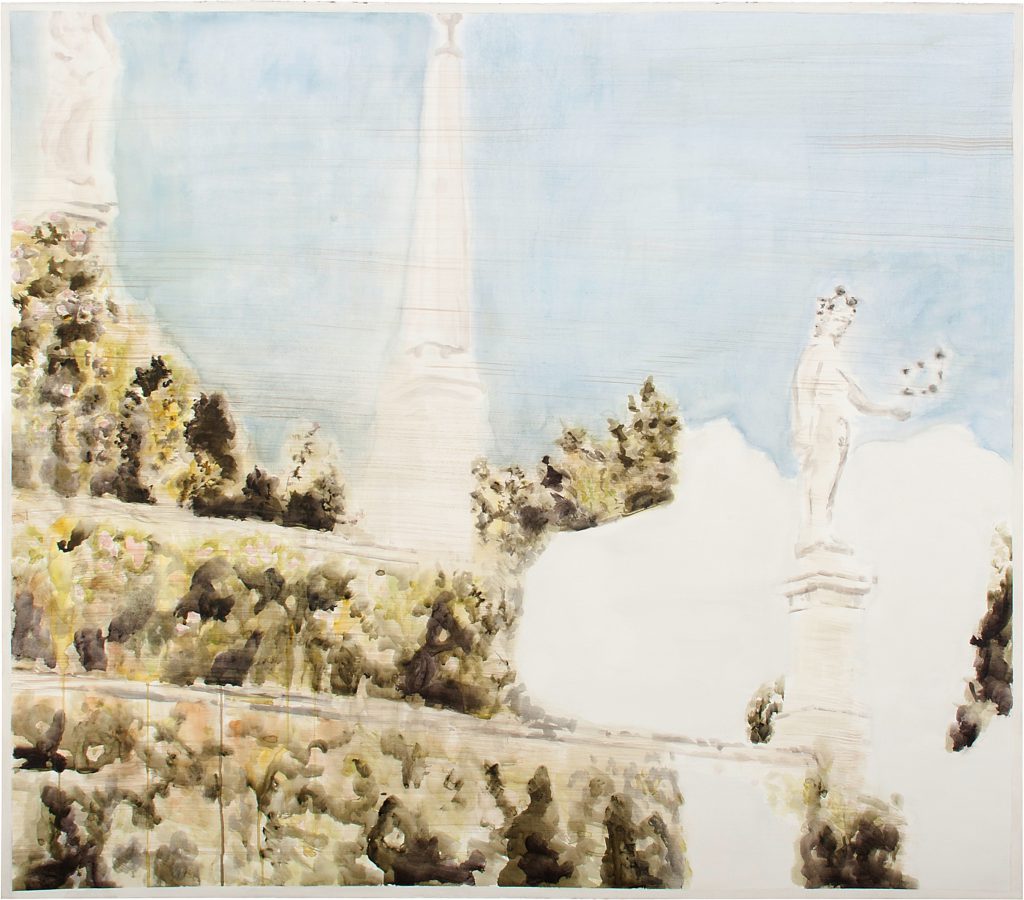

Park

2013

Watercolour on paper

114 × 130 cm

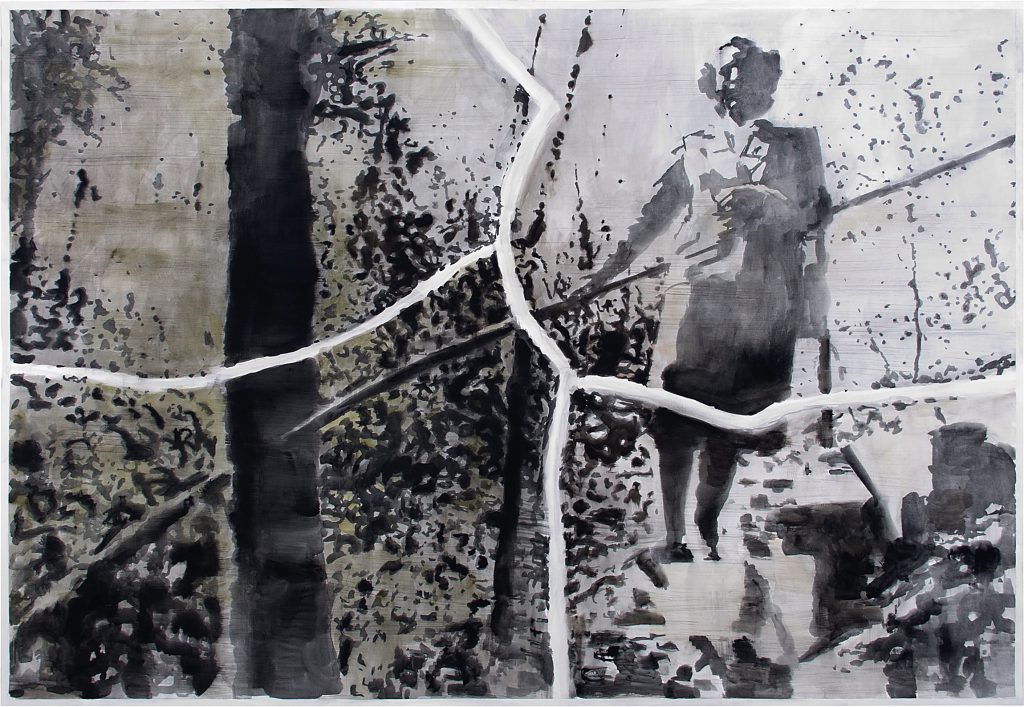

Waldtreppe

2013

Watercolour on paper

90 × 130 cm

Ruine (Ruin)

2013

Watercolour on paper

154 × 227 cm

Schlafender Knabe (Sleeping Boy)

2013

Watercolour on paper

70 × 90 cm

Portrait

2013

Watercolour on paper

130 × 114 cm

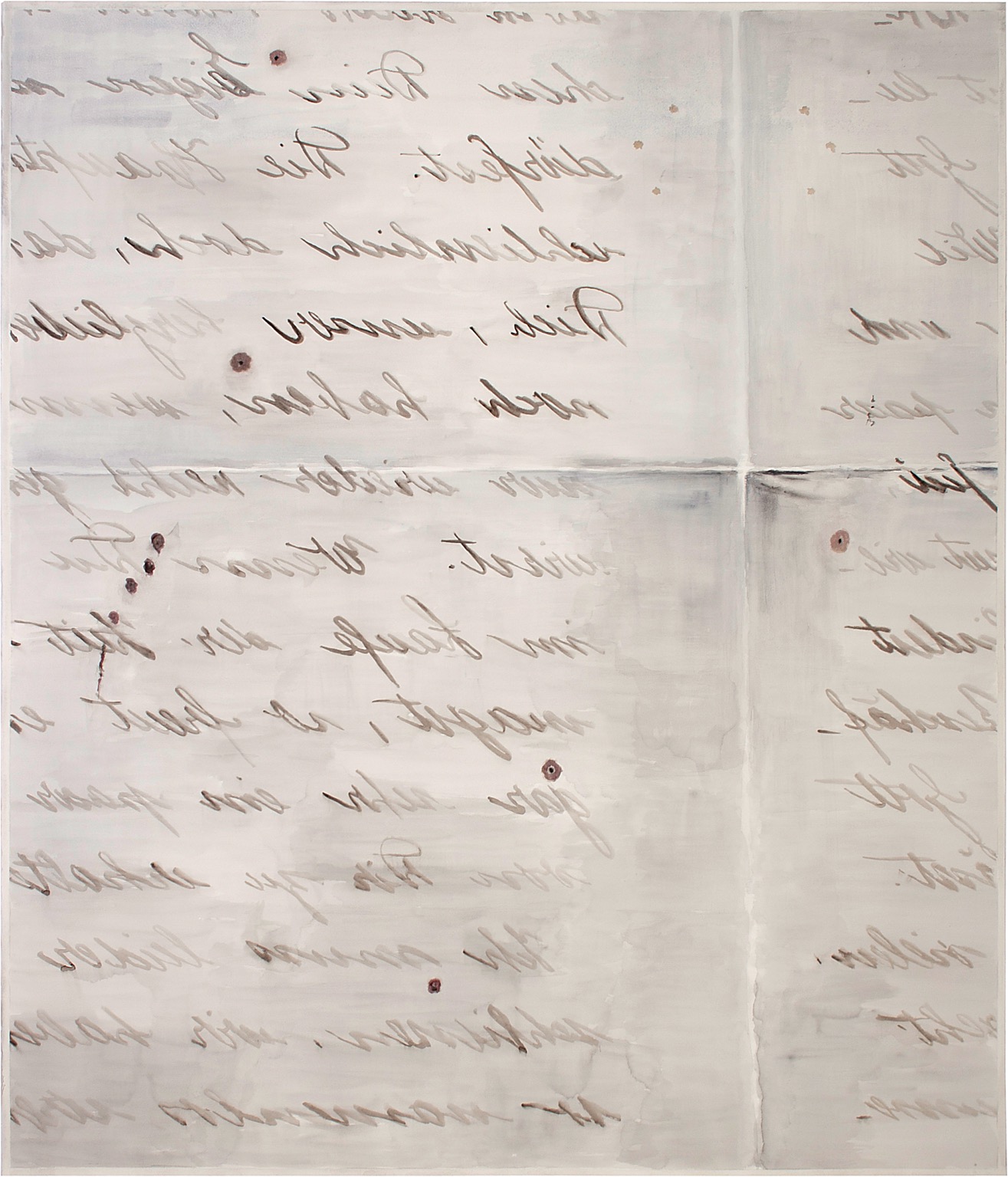

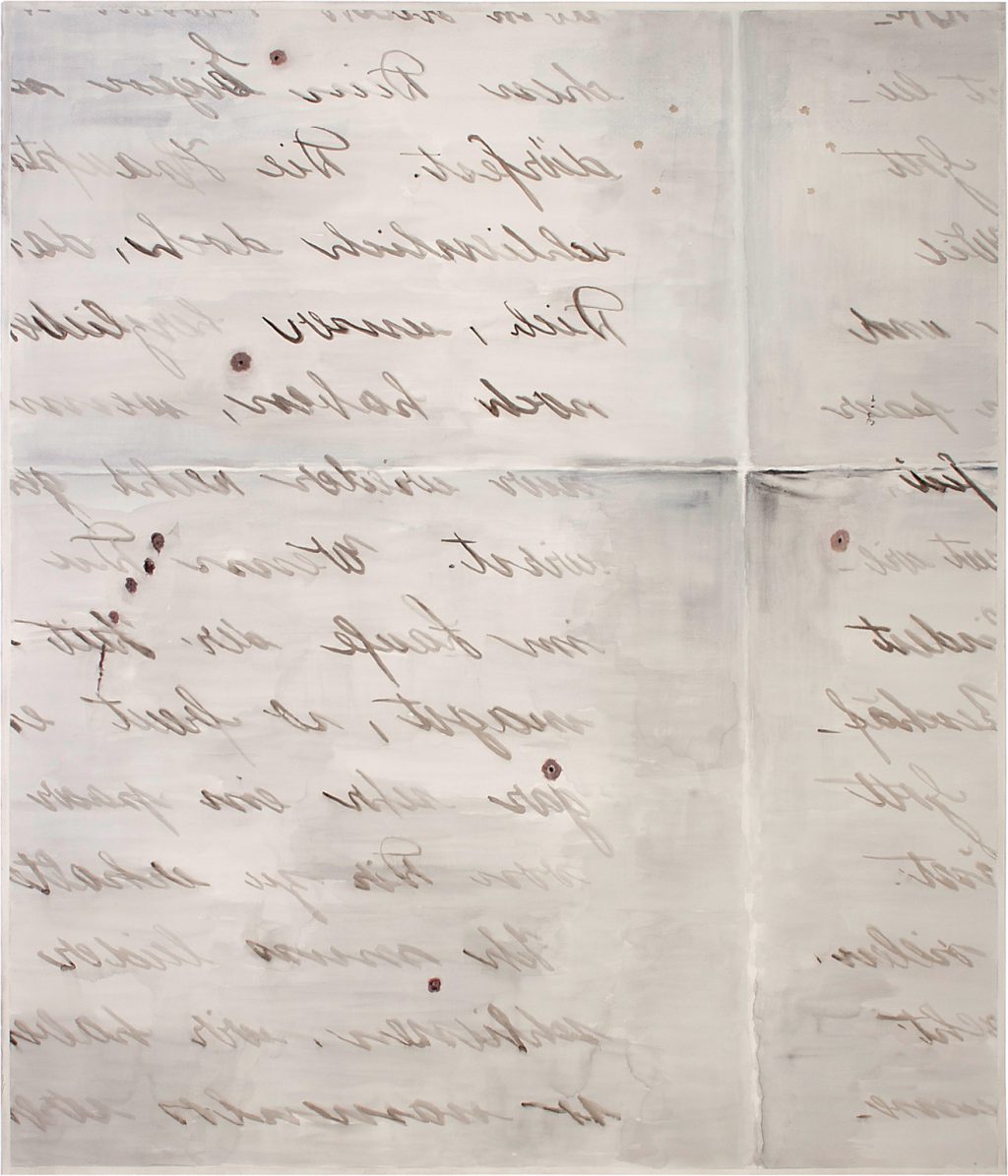

Brief (Letter)

2013

Watercolour on paper

180 × 154 cm

Beobachter (Observer)

2013

Oil on canvas

195 × 195 cm

Text

In his new series, Der Brief (The Letter), Wittwer again bases his works on pictures of times past in order to take the question of image, impression and reality in the digital age to a deeper level. His central theme, focusing on the fragility of the idyllic, is expressed in images of captivating beauty and sensuality. For the first time though, he now turns to his own family history; he opens the photo albums and archive boxes of his parents and grandparents, displaying intimate witnesses of family history on large-scale formats.

This candid look back appears like a logical deeper immersion in the theme of Verwehung (Drift, 2008), a group of works about glory and hardship of the population of Eastern Prussia before and during the second world war. Let’s recall: Wittwer’s grandfather worked as a milking foreman on an Eastern Prussian country estate, and,in 1932, just before Hitler seized power, his music-loving father was drawn to Berlin, where he lived through the war. As a Swiss national he was not conscripted, and he managed to escape to Switzerland in 1945. Yet Verwehung was not a work about his personal family history; all of his sources Wittwer found on the internet. Instead of focusing on historical research, he pursued the question of whether, with the time distance and our knowledge of history, we are at all capable of looking objectively at the testimony of what happened to – for the most part – anonymous families in that era.

Continue reading

It is, however, quite evident that in his new, autobiographical works, numerous themes and even concrete motifs from various series of the past 20 years appear. Sometimes they just pop up briefly, sometimes they seem to be the synthesis of a long search. Very telling is also the exclamation of Wittwer’s long-term assistant when he first saw the new pictures: “It’s all there already!” So is the new group of works a key to all his previous work? Wittwer doesn’t mind admitting that the scrutinizing gaze at the strange or alien, the “artist’s view”, is always steered by one’s own experiences. Each topic that he picks has such personal relevance. But consciousness cannot always directly access these spiritual contents, and only the search for context can unearth them.

A good example from Wittwer’s oeuvre are the Ruinen-pictures, which he has been producing regularly and above and beyond the other series since 1990. For all his life, Wittwer’s father had never talked about his experiences in war-torn Berlin. The missing descriptions prompted the son to think up his own images and over the years, like a puzzle, he formed an idea of what these times must have been like for his father. A central image of the series, the mysterious Ruine (created in 2013, like all the works described here), is based on one of the few photographs that his father brought with him from Berlin. The large-scale watercolor shows a row of badly damaged houses, above which the numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 hover – carefully drawn in blue handwriting. Their position suggests that the numbers indicate the four house entrances, but are not the real house numbers. (In the last months of the war, façades were often used as notice boards with messages about tenants, about people who had moved away and about the dead – messages for surviving loved ones and home-comers, graffiti against the oblivion of war.) What purpose the numbers on the photograph served is lost in time. We do know that is was not his father’s home; and that the photo didn’t end up with the others in the family album, but was locked separately in the sideboard.

The artist returns to the image of this small array of numbers in the ink-jet piece Waldstück, where he places them above a misty wood in the mountains. Now the arrangement very obviously does not endow meaning to the work, but just exudes calm and quiet, and perhaps also grief. Woods and mountains are seen often in the group of works – and not just because days out in nature are a traditional motif and depicted frequently in family albums. As central mementos of a carefree childhood, they are also readily accessible. In the monumental ink-jet Waldstück negativ, a young Uwe accompanies his father and grandfather into a dark forest to chop wood. What looks like a scene from a Grimm’s fairy tale is made non-threatening through the inclusion of enchanting ghost-lights. Such visual elements have no discernible function for the spectator, and are reminiscent of surrealist practices.

In Schlafender Knabe, a further key picture in the exhibition, the artist portrays himself as a seven-year old child sleeping peacefully and dreaming on a lively-patterned carpet. Wittwer considers childhood as a time of “semi- and subconsciousness” and of uninhibitedness. The dream level and the switching between consciousness and subconsciousness therefore take on a special significance in the new works. The motif of textile patterns also runs like a common thread through all his works.

The name-giving letter, which the exhibition Brief is titled from, was written by a great-aunt of the artist’s in the year 1921. The fact that it has ended up in large-scale format on a gallery wall nearly a century after it was written and subsequently passed down the generations, points to a relevance beyond its actual contents. Wittwer has put a mirror image of the letter up, making an immediate reading impossible. The effect of the writing forming an image is enhanced through the choice of the particular detail, and the focus on the fold. Der Brief is a late addition to the other works in the series. The original was hanging between other documents and photographs in his studio – and at some point fit the mood of the artist while he was painting.

In Wittwer’s works you can generally recognize the intellectual approach, the clarity and the incisiveness more easily than the emotion. If he allows too much sentiment, he once explained, the subject slips from his hands; so the creative process for him is one where the balancing of emotional and analytical elements is very important. An interesting aspect of this group of works is that not each piece is quite so balanced, but that some works are of an unselfconscious emotionality, while others are of an intellectual assertiveness, achieving a balance overall.

A very personal work is Stillleben negativ, depicting a small vase. During his time at a Kantonsschule (comparable maybe with an English grammar school), Wittwer attended a voluntary pottery class. As the first serious encounter with his own creative abilities, this set him on a path to become an artist. The vase in the picture was made in that pottery class, and when Wittwer, together with his brother, dissolved his parents‘ household after his father’s death, the vase went to the thrift shop. What remains is the photograph – and this beautiful and unsentimental still life.

The photograph was quite likely taken by Wittwer’s mother, who managed to get her hands on a camera quite early. In Waldtreppe the mother is herself the subject of a photograph taken by the father: elegantly dressed in a Sunday coat, she descents a steep staircase, posing briefly for the camera. Naturally we draw parallels to famous predecessors of the composition, the nudes by Duchamp or Richter, but there is also a previous variation of this in Wittwer’s own oeuvre, only with an unknown Eastern Prussian woman instead of his mother. In the more recent Waldtreppe, rough tears dominate the picture – as if someone had ripped the photograph of the mother to shreds in a fit of temper, only to patch it up again poorly afterwards. This technically sophisticated trompe l’oeil painting Wittwer calls “a teensy masterpiece” or “Bravourstückli”, as painting in watercolors requires the artist to plan composition, color application and open areas meticulously in advance.

Wittwer made all of the works in this exhibition on paper. Apart from the watercolor method, he again uses digitally edited inkjet prints, but for the first time he has used oil paint to work over some of the prints. The limited color range of the works and the often sparing use of color convey a beautiful metaphor of fading, not just of these souvenir pictures, but also of memory itself.

Finally, in Portrait, Wittwer himself is again to be seen as a small boy. He holds in his hands a pair of binoculars – oblivious to the fact that this instrument will obtain an importance for the adult artist that goes well beyond its sensory perceptibility. The binoculars, which Wittwer already dealt with in his Rear-Window-pictures, enable observation as an irritating combination of keeping a distance and zooming in, gawking and empathy. This child(self)portrait is a pre-emption of the complex Beobachter, one of only two paintings (oil on canvas) in this show. It shows the artist as a sixteen-year old: he stands with his back to a glorious painting depicting the Watzmann mountain – an homage to Caspar David Friedrich’s masterpiece of that name and to the medium of painting itself.

In autobiographical terms, the Beobachter captures a turning point in Wittwer’s life: it will be the last time that he spends his holidays with his parents; soon he will discover his interest in the creative arts. Chronologically the picture is the last one in the series, the end of childhood. Artistically it is the start into a new series, one in which the analytical element may well dominate over the emotional again.